| Aldbourne picture postcard village |

For information about membership of The Richard Jefferies Society contact: Margaret Evans Membership Secretary 23 Hardwell Close Grove Nr. Wantage Oxon OX12 0BN England Tel. 012357 65360. See note.

* THREE HUNDRED AND FIFTY COPIES OF THIS EDITION PRINTED FOR SALE *

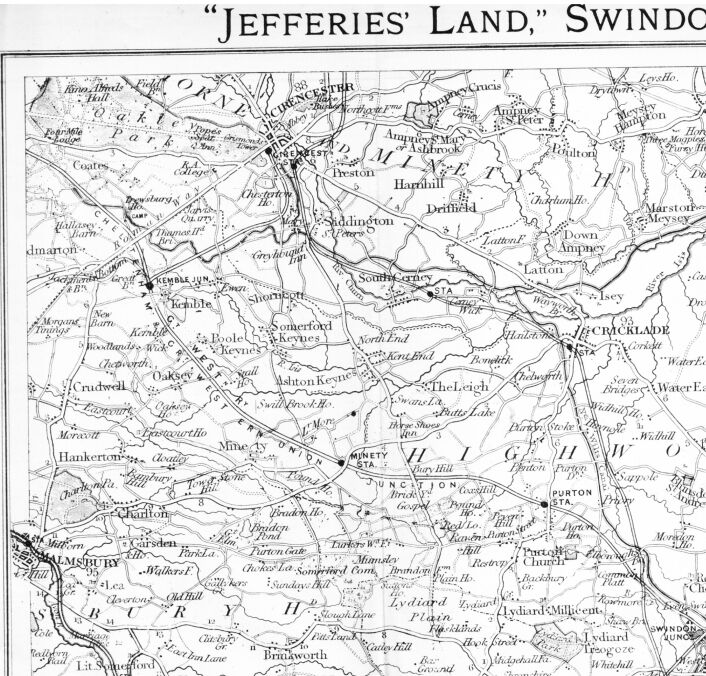

JEFFERIES' LAND

A History of Swindon

and its Environs

BY THE LATE

RICHARD JEFFERIES

EDITED WITH NOTES BY GRACE TOPLIS

WITH MAP AND ILLUSTRATIONS

London

Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co Ltd

wells, Somerset: Arthur young

MDCCCXCVI COPYRIGHT

All Rights Reserved

| Aldbourne picture postcard village |

vii

|

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS |

|

|

CHAP. |

PAGE |

note.The illustrations are reproductions from drawings by Miss Agnes Taylor, Ilminster, mostly from photograph taken especially by Mr. Chas. Andrew, Swindon.

| INTRODUCTION |

LIFE teaches no harder lesson to any man than the bitter truth as true as bitter that "A prophet is not without honour, save in his own country, and in his own house." And foremost among modern prophets who have had to realize its bitterness stands Richard Jefferies, the "prophet" of "field and hedgerow" and all the simple daily beauty which lies about us on every hand. The title of "The Painter of the Downs" might be given to him, as it was to the veteran artist H. G. Hine, for his glorification of his native country in wordpictures as vivid and glowing as the colours on the canvas.

But Wiltshire never realized, during his lifetime, the greatness of the man whom she had reared, and it is open to question whether she honours his memory now. "I can't see what people find to admire in his books, I can see nothing in them" has been said again and again by those who live among the sights and scenes which he loved so well, and made familiar to jaded readers in the town.

For Sir Walter Besant was right. It is the Londoner who appreciates what Jefferies has to tell of "the Life of the Fields." " Why, we must have been blind all our lives; here were the most wonderful things possible going on under our very noses, but we saw them not.

Nay, after reading all the books and all the papers every one that Jefferies wrote between the years 1876 and 1887, after learning from him all that he had to teach, I cannot yet see these things. I see a hedge; I see wild rose, honeysuckle, black briony herbe aux femmes battues, the French poetically call it blackberry, hawthorn, and elder. I see on the banks sweet wild/lowers, whose names I learn from year to year, and straightway forget because they grow not in the streets. I know very well, because Jefferies has told me so much, what I should be able to see in the hedge and on the bank besides these simple things; but yet I cannot see them, for all his teaching. Mine alas!are eyes which have looked into shop windows and across crowded streets for half a century, save for certain intervals every year; they are helpless eyes when they are turned from men and women to flowers, ferns, weeds, and grasses; they are, in fact, like unto the eyes of those men with whom I mostly consort.

None of us-poor street-struck creatures can see the things we ought to see." These are the readers who appreciate Jefferies.

And of these are formed the elect forty thousand who feel the charm of his written words.

"His own country" may question his right to be numbered among her great men, but he is safe in his own niche in the Campo Santo of English Literature, and neither neglect nor disparagement avail now for hurt or wounding.

In a handy little Tourist's Guide to Wiltshire, Mr. R. N. Worth says: "Wiltshire needs not to be ashamed of its worthies," and gives a list of honoured names; but the name of Richard Jefferies is not on his list. "save in his own country, and in his own house." The spell of Jefferies Land must be sought in his later books: Wild Life in a Southern County, Wood Magic, Round About a Great Estate, etc., etc.; or, better still, it may be sought and found on a summer's day by any wayfarer on the Downs who possesses a seeing heart and eye. But, in his early days, Jefferies could find no utterance for the vision which came to him, and yet, even then, in his crudest and most unformed period, he was loyal to his country, and desired to do it honour. His History of Swindon and its Environs was written in the days when he worked for the North Wilts Herald, in which the last pages appeared in June, 1867, when he had but a boy's second-hand acquaintance with the facts and traditions he collected so laboriously, "I visit every place I have to refer to, copy inscriptions, listen to legends, examine antiquities, measure this, estimate that; and a thousand other employments essential to a correct account take up my time. . . . To give an instance. There is a book published some twenty years ago founded on a local legend. This I wanted, and have actually been to ten different houses in search of it; that is, have had a good fifty miles' walk, and as yet all in vain. However, I think I am on the right scent now, and believe I shall get it." There was no sparing of time and labour in this early work of his. Let this be remembered before it receives harsh judgment.

In the preface to The Early Fiction of Richard Jefferies, obvious criticism is anticipated, and reasons are given for the republication of his boyish writings. The latter may be quoted in this volume.

"Why then do these early efforts make their appearance in this permanent book-form ? ''For two reasons; the least worthy of which is, that a book-lover yearns to make his collection complete, and the Juvenilia of other great writers are 'taken as read' and placed with their fellows lest one link should be missing.

But the reason for the student is that they illustrate as can be done by no comment from outsiders the mental growth of the man, and his unusually slow development as a writer.

This is why they possess interest in the eyes of a Jefferiesian student, and why they are offered to the reading public as intellectual curios." The task, therefore, of editing his History of Swindon presented some unusual difficulties, due to two facts that it was written during the period of his immaturity; and that thirty years have elapsed since he wrote it. The first difficulty lay in the style of his writing, in his authoritative pronouncements on matters antiquarian far beyond the bounds of his boyish knowledge of the past; the second difficulty lay in the changes which thirty years have brought to Swindon, and in the difference between the Then and the Now.

After much consideration, it seemed better to issue the book as his work, and as he wrote it, with all its merits or faults as the reader may pronounce. To bring the History of Swindon up to date, to eliminate all the "facts" which time has disproved, to revise his "antiquarian" statements with the fuller knowledge of a later day, would possibly have resulted in a more useful book of reference, but it would not have been the work of Richard Jefferies. The Editors task has been confined, therefore, to mere annotation and explanation of what the young Jefferies wrote; and if local antiquarian societies will do it the honour of rectifying crude judgments, and disproved "facts" so much the better for the wider public of readers whom this volume will never reach.

Grace Toplis.

|

BIBLIOGRAPHY |

In addition to the usual historical works of reference, the following authorities have been consulted:

| Wiltshire, extracted from Domesday Book | H.P. Wyndham |

| Wiltshire The Topographical Collections of John Aubrey F.R.S a.d. 1659-70. Corrected and enlarged by J. E. Jackson. 1862 | Aubrey. Jackson. |

| Beauties of Wiltshire. 1825 | J. Britton. |

| The Natural History of Wiltshire. Edited and Elucidated by J. Britton. 1847 | Aubrey Britton. |

| Tracts relating to Wiltshire. 1856-72. | J.E.Jackson. |

| Annales of England. 1615 | Stow--Howes. |

| History of England under the Norman Kings.Translated from German of Dr. Lappenberg, by Benjamin Thorpe 1857. | Lappenberg. Thorpe. |

| Dictionary of National Biography | Ed. Leslie Stephen. |

| Autobiography of John Britton. 1850. | Britton. |

| Ancient Hills. Roman Era . | Sir R. Hoare. |

| History of the Rebellion.Edited by Macray. 1888. | Clarendon. |

| History and Antiquities of the Duchy of Lancaster. 1817 | Gregson. |

| Wiltshire Archaeological Magazine : "The White Horses of Wiltshire." | W. C. Plenderleath. |

| Reliques of Ancient English Poetry. | Thomas Percy. |

| Six Old English Chronicles. (Ethelwerd, Richard of Cirencester, etc.). | A. Giles. |

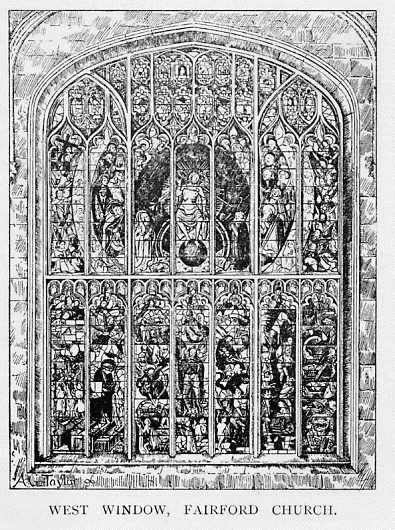

| The Fairford Windows. Monograph. | Rev. J. G. Joyce. |

| Round the Works of our Great Railways. | |

| Swindon: Fifty Years Ago, More or Less. | W. Morris, |

JEFFERIES LAND

|

CHAPTER I ANCIENT SWINDON |

THE early history of Swindon is involved in obscurity. The works by whose aid the mist of antiquity has in many places been considerably cleared away, until the outline at least, if not the details, of the structure our forefathers reared, is perceivable, here give no assistance. There does not appear to have ever been a monastery at Swindon. Its streets no doubt have been perambulated by the massthanes, the hooded noblemen of the cloisters, but they do not seem to have ever taken up a permanent residence.

There is no chronicle of Swindon, so the want which the monks supplied in other places is severely felt here. It is impossible to compile an uninterrupted narrative. Facts there are, and traditions there are, scattered up and down a long vista of years; but no art, short of fiction, could combine them into a chronicle.

It does not appear that any great event of national importance ever took place at Swindon no royal murder or marriage; no battle seems to have been fought, no castle built, not even a castrament remains in Swindon itself to bear a witness to bygone deeds of blood blood which writes itself so indestructibly wherever it has been spilt. Hence no writer, no historian, mentions Swindon, nor gives any account of it as a place the memory of which was worth preserving for what had occurred there.

Even the etymology of the name Swindon is uncertain. The most probable conjecture assigns its origin to the Danes. In the year 993 the celebrated Sweyn1 king of Denmark, 1 Swend was the son of Harold Blaatand, and received at baptism the name of Otto, but he soon cast away the Christian faith, and waged war on behalf of Thor and Odin.

He probably took a part as a private Viking in the first three years of piracy which devastated Wessex. Died at Gainsborough, 1014.

During one of his seasons of adversity he was won back accompanied by Olave,1 king of Norway, made his first piratical descent upon the coast of England. Though bought off several times, he invariably returned with increased forces, and at length, coming to Bath, received the homage of the western thanes, or noblemen, and ascended the throne of England. This was in the year 1013 a.d. Sweyn was much of his time in the western counties, hence it is conjectured that Swindon means no more than Sweyn's-don, dune, or hill the hill of Sweyn.

Dune, now usually pronounced don, was a Saxon word for hill it survives still in down, of which there is a sufficiency in the neigh-

| to the faith from which he had apostatized, and became a zealous founder of Churches. |

| Danish writers testify to his piety, but German and English writers are silent on the subject. |

| For St. Edmund he had a special hatred. In marching to Bury to plunder the minster dedicated to him, he was suddenly stricken with the malady from which he died. |

| Tradition says he had a vision of the saint riding armed to destroy him. His body was embalmed by an English lady, and taken, at her own cost, to Denmark, where it was buried in his own church of Roeskild. |

| Freeman says of Swend that he was a great man, if greatness consist in mere skill and steadfastness in carrying out An object; his glory is that of an Attila, or a Buonaparte. |

1 Olaf Tryggwasson.

bourhood. Should this conjecture be correct, it would follow that Sweyn must have had some connection with this place, resided here, or made it the scene of some of his exploits.

Strange to say, this Sweyn seems to be the first and the last royal celebrity who came into connection with Swindon. In eight centuries nothing of national importance is recorded as taking place here, except this visit of Sweyn, and even that is a matter of supposition. This is tolerably good evidence that the town was for many hundred years of little or no importance. A history of Swindon, properly so-called, would not extend over a period of more than one hundred years: yet the place seems to have existed for eight hundred years.

The only way in which its existence can be rendered evident is by tracing the descent of the surrounding landed property from owner to owner.

The first of whom any record appears to exist as possessing land at Swindon was Earl William, a celebrated nobleman in the days of Edward the Confessor, whose reign extended from 1042 to 1066. The domain of Swindon had in all probability previously belonged to the Crown, since it is mentioned that Earl William held it by right of charter, and to the Crown it again returned about 1050 a.d., that nobleman exchanging it for an estate in the Isle of Wight. In what manner it became sub-divided does not seem recorded, but when Domesday Book was compiled by order of William the Conquerorbetween 1082 and 1086the lands at Swindon were in the possession of five persons. Three of these were small, and the remaining two extensive proprietors. All were public men, attendants upon the Conqueror, probably Normans, who came into possession by right of conquest, as a reward for following their master. The first in point of grandeur, celebrity, and the extent of his possessions, was no less a person than Odin.1 chamberlain to the Conqueror. The

| 1 Swindon, as referred to in Domesday Book. "Odinus, the chamberlain, holds Svindone. Torbertus held it, T. R. E., and it was assessed at 12 hides. Here are 6 ploughlands. |

| Two of them are in demesne with 2 servants. And 6 villagers and 8 borderers occupy 3 ploughlands. The mill pays 4 shillings. Here are 30 acres of meadow, and 20 acres of pasture. It was valued at 60 shillings; now at 100. |

| Milo holds 2 hides of this manor, and he has 1 ploughland. |

| Odinus claims them." |

| [Odinus Camerarius tenet Svindone. Torbertus tenuit |

second was the Bishop of Bayeux. Odo, Bishop of Bayeuxof course a Norman, for at that date there does not seem to have been a single British bishop who rendered himself infamous by his tyranny and ambition. When an insurrection broke out in the north, occasioned by the intolerable oppression of another Norman bishop, he of Bayeux marched there with an army, slaughtered the inhabitants, and though an ecclesiastic, actually plundered the cathedral of Durham. He was now found to have a design on the Papacy, and set sail for Rome, attended by a retinue of knights and barons, when King William, who scarcely desired to see a vassal of his an infallible pope, met him off the Isle of Wight, and seized him with his own hands.

The bishop cried out that he was a "clerk and minister of the Lord." "I condemn not a clerk or a priest, but my count, whom I set over my kingdom," replied

| T. R. E. et geldabat pro 12 hidis. Terra est 6 carucatae. |

| In dominio sunt 2 carucatae, et 2 servi. Et 6 villani et 8 bordarii cum 3 carucatis. Ibi molinus reddit 4 solidos. |

| Et 30 acrae prati, et 20 acrae pasturae. Valuit 60 solidi; modo 100. De hac terra tenet Milo 2 hidas et ibi habet i carucatam. Odinus eas calumniatur.] |

the king, and he was sent as a prisoner to Normandy.1

|

1 Stow, in his Annales of England, says :" About this time many tempests raging in the world, certaine Soothsaiers of Rome declared who should succeed unto Hildebrand in the Popedom, they affirmed after the decease of Gregorie, Odo to bee Pope of Rome. Odo Bishoppe of Bayou, hearing this, who (with his brother) governed the Normanes and Englishmen, little esteeming the power and riches of the west kingdome, unlesse by right of the Popedom, might largely rule all ye inhabitants of ye earth, he sendeth to Rome, he buyeth a palace, he seeketh out the senators, who with great gifts he given he joyneth with him in amitie, he sendeth for Hugh, Earle of Chester, and a great company, . . . and hartely prayeth them to goe with him to Italy . . . beyond the river of Poo. Prudent King William, when hee heard of such great preparations, allowed not thereof, but thought it to be hurtfull to his kingdome, and many others, wherefore, he hastily saileth into England, and sodenly unlooked for in the Ile of Wight met with Odo the Bishoppe, and now desirous with great pompe to saile into Normandy, and there ye chiefest of his Realme being gathered together in the king's hall, the king spake in this sort. 'Excellent Peeres, hearken my wordes diligently, I beseech you give unto me your wholsome counsaile.

"'Before I sailed over the Sea into Normandie I commended the government of England to my brother the Bishoppe of Bayou. . . . "'My brother hath greatly oppressed England and hath spoiled the Churches of their lands and rents, hath made them naked of the ornaments given by our predecessors, and hath seduced my knights and contemning me purposeth to traine them out beyond the Alpes, into foraine kingdomes, |

Such was the Bishop of Bayeux, whilom owner of a great portion of the land registered in Domesday Book as Swindon. His history reveals what will now appear a strange state of matters. When Swindon was in its infancy eight centuries ago, a bishop commanded an army, and plundered a cathedral, than which two things it would be impossible to name others more opposed to what is at present considered the mission of a clerical dignitary.

Moreover, he was the "count whom I set over my kingdom." Here is a bishop, a count, a general, and a robber, all in one. Could anything show more conclusively the confusion which followed close upon the Conquest?

|

an over great dolour grieveth my heart; especially for the Church of God, which he hath afflicted. . . . Consider you worthely what is to be done hereupon, and I beseech you insinuate it unto me." "And when all they fearing so great a performance, doubted to pronounce sentence against him, the valiant king saide, hurtfull rashnesse is alwaies to bee repressed....

" Now the king committed his said brother Odo to prizon, where he remained about ye space of foure yeers after, to wit, to the death of King William." This is confirmed by Sappenberg, trans. Thorpe, in his History of England, quoting from William of Malmesbury and others. |

Under the Bishop of Bayeux there were two tenants; they were named Wadard, hence they were probably related. Alured of Marlborough also held land at Swindon. He seems to have been a very extensive proprietor in North Wilts at that date. One Uluric, too, owned property here, and the fifth was Ulward, the king's prebendary, whatever that may mean.

The lands registered as Swindon in Domesday Book afterwards received distinctive names.

There was Haute, High, or Over Swindon, Nether Swindon and Even Swindon. Haute, High, or Over Swindon was undoubtedly upon the hill. Over is a prefix not uncommonly found before names of places indicating their position to be over, or above that town whence they drew their origin, or with which they were connected. An instance is Overtown at Wroughton, which still retains its name, and whose position indicates its origin, being situated high up upon the hill over-looking Wroughton. Besides Haute, Nether, and Even Swindon, there was Wicklescote, now known as Westlecott. It may be observed that north-east of Westlecott is a hill known as Iscott hill. Cot comes from a Saxon word meaning habitation, and is still preserved in cottage. It is probable that these two places Westlecott and Iscotthave been the seat of habitations from the earliest times. Wicklescote afterwards belonged to persons of the names of Bluet and Bohun. Bohun is a name very celebrated in English History during the reign of Edward I. That monarch proceeded to tax both clergy and laity at his pleasure, heedless of the Great Charter, but was at length compelled by Humphrey Bohun and Roger Bigod,1 two great noblemen, not only to

|

1 Roger Bigod, fifth Earl of Norfolk, Marshall of England, born 1245, son of Hugh Bigod, justiciar. When called upon to serve in Gascony, while Edward took command in Flanders, he refused.

" By God, earl, you shall either go or hang." " By God, O king, I will neither go nor hang." The Council broke up, and Bigod and Bohun were joined by more than thirty of the great vassals. In answer to a general levy of the military strength, the two earls refused to serve in their offices of marshall and constable, and were therefore deprived of them. When Edward sailed for Flanders, leaving the Prince in charge, they made the most of their opportunity, and protested boldly against exactions, being joined by the citizens of London. An assembly of the magnates and knights of the shires was called, Bigod and Bohun appeared in arms, the prince was obliged to confirm the charters. Upon the return of the king the earls demanded of him a confirmation in person, to which after long hesitation he yielded. After this, and the death of Bohun in 1298, Bigod's power seems to have collapsed. He made the king his heir, and gave up his marshall's rod. Surrendered his lands and title, receiving them back intail. A chronicler ascribes this surrender to a quarrel between Roger and his brother John. 1306. Bigod died without issue, and in consequence of his surrender his dignities vested in the crown. He married twice : 1. Alina, daughter and co-heir of Philip Basset, chiet justiciar of England in 1261, and widow of Hugh le Despenser, chief justiciar of the barons. 2. Alice, daughter of John of Hainault. Humphrey Bohun, fourth Earl of Hereford, son of Bigod's colleague, took an active part in opposing the Despensers and Edward II. He was killed at Boroughbridge,1322. A Bohun held the Basset lands.Dictionary of National Biography. |

confirm that charter, but to add a clause to it by which it was provided that the nation should never in future be taxed without the consent of Parliament, a wise enactment which has secured the property of the subject against the rapacity of rulers, and also proved the foundation of England's wealth. All honour to the illustrious Humphrey Bohun. Wicklescote was then held under the manor of Wootton Bassett. Later, in the reign of Edward III., who occupied the throne from 1327 to 1377, the Everards and Lovells were proprietors. A Katherine Lovell, seemingly in the reign of Henry IV. (1399 to 1413), gave certain lands at Wicklescote to Lacock Abbey, which, at the dissolution of monasterieswhich took place in the year 1535were bought by John Goddard, Esq., of Upper Upham. Sir Edward Darell, of Littlecote, near Hungerford, had lands here in the early part of the reign of Edward VI. John Wroughton had the manor in the seventh year of Henry VI., that is, in 1429.

The manor of High Swindon was conferred by King Henry III. (reigned from 1216 to 1272) upon a relation of his, in fact, his halfbrother, William de Valence, the celebrated Earl of Pembroke, of Goderich Castle. His son, Aylmer de Valence, held it in the year 1323. Valence is a name familiar to the readers of Sir Walter Scott's novels. Aylmer de Valence, it will be remembered, is the hero or one of the principal characters in Castle Dangerous; and is there represented as the nephew of the Earl of Pembroke. The widow of Aylmer de Valence held the manor in 1377.

She was known as Mary de St. Paul, Countess of Pembroke, and her memory has been perpetuated in consequence of her having founded Pembroke Hall, Cambridge. Aylmer de Valence having died without issue, part of the estate fell to the daughter of his sister, Elizabeth Comyn. She married Richard, second baron Talbot of Goderich Castle, who thus became owner of this part of Swindon. The Talbots were a celebrated family. Shakespeare has immortalised the name in one of his historical dramas. Later, in 1473, it belonged to John, Earl of Shrewsbury. At this date the manor was held under what was known as the Honor of Pont'large.1 At length, in the year 1560, the estate was purchased by Thomas Goddard, Esq., of Upham, ancestor of the present owner, A. L. Goddard, Esq.

Phillip Avenell had landed property at Swindon in the time of Edward I. He held it under the Abbess of Wilton. The names of Avenell, Spilman, and Everard are found here about 1316 a.d.

| 1 Or Pont de lArche. |

Olivia1 Basset, wife of Hugh Despensera distinguished namehad an estate at Swindon in the seventh year of Edward I., that is, in 1279. The grandson2 of this Olivia Basset married Eleanor, co-heir of Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester.3 In the thirty-third year of the burly monarch, Henry the Eighth, a Wenman owned the estate known as Even Swindon. The Abbey of Malmesbury, the Monastery of Ivychurch, and later, the Everards and Alworths also held portions of these lands, which were originally in the hands of only five proprietors. The Wenman family seem to have purchased their property here about 1541, or soon after the dissolution of monasteries. At the same time, Sir Thomas Bridges bought some lands at Swindon. He was the ancestor of the Duke of Chandos. In the days of the Virgin Queen Elizabeth the woods, "super Rectoriam," were purchased from the Crown by Thomas Stephens, of Burderop.

The Viletts also held landed property at Swin-

| 1 Her name is also given as Oliva, or Aliena. |

| 2 Hugh Despenser, junior |

| 3 Hence the "Coate of Clare." |

don; the family is now (1866) represented by Mrs. Rolleston, of the Square, Swindon.

At the present day (1866) the largest landed proprietor of Swindon is A. L. Goddard, Esq.

He also owns the estate known as Broome.

This, in the reign of Edward I., belonged to the priory of Martigny. Afterwards, at the dissolution of the monasteries, it came into the possession of the Seymours, an ancient and widespread family. Later it descended through Katherine, the daughter of Charles, sixth Duke of Somerset, to the Wyndhams of the Egremont house; from whom it was purchased by the present owner. When Aubrey, the wide- famed Wiltshire antiquarian, came to Swindon about two centuries ago, he seems to have visited Broome, since he alludes to it in the following passage: " Mem.At Brome, near Swindon, in a pasture ground, near the house stands up a great stone, q. Sarsden,1 called Longstone, about 10 feet high, more or less, which I take to be the remayner of a Druidish Temple; in the ground below are many stones in a right line, thus: O O O O O O O."

| 1 The etymology of this word is uncertain. Aubrey |

The stone seems to have disappeared, but to this day the field is known as Longstone field.

There still remain a number of Sarsdens scattered about, but without any apparent attempt at order. A similar stone is said to have once stood in Burderop Park, about a mile further.

Whether Aubrey was right or wrong in his conjecture concerning the Druidical origin of the assemblage of stones which he saw, it is now of course impossible to tell, unless some fortunate discovery should throw light upon the matter. It may be remarked that on the slope of the field known as Brud-hillsome say

|

derives it from Sarsden (Cesar'sdene?) a village three miles from Andover. Other suggestions are A. S. selstan = great stone. A. S. sar = grievous, stan = a stone. A. S. sesan = rocks. Sarsens or sarsdens are also known as grey wethers or Druid stones.Hunter.

Canon Jackson comments: "Of the great stones mentioned by Aubrey none are now remaining." Mr. Morris says: "I resolved on finding out, if possible, what had become of 'the remayner of a Druidish Temple,' and after some years I was rewarded for my trouble by making the discovery that the stones were actually sold to the Way- wardens of Cricklade, and removed to that town, where they were broken up and used to make good the pitching in the streets. ... If this was the use the Swindonians of old were prepared to make of 'the remayner of a Druidish Temple,' the world at large may feel thankful that they had no control over Stonehenge and Avebury." |

Blood-hill, a name that would indicate fighting adjoining the Park at Swindon, there is beside the footpath, a similar row of Sarsden stones to those seen at Broome by Aubrey, though these are much sunk in the, earth.

The extent of Swindon, both during the Saxon times and for centuries after, was in all probability inconsiderable, that is, as a town.

There were probably a few great mansions scattered here and there, the residences of the tenants under the great families, who from time to time owned the adjacent estates; and near these the cottages of the labourers. The remains still existing of this period are so very inconsiderable that it is next to impossible to found even a probable conjecture upon them.

A few years ago what was considered a Saxon arch or doorway was discovered in a cellar in High Street, and whilst making some excavations in the New Road, it was stated that the Workmen came upon a Saxon pillar. Remains Such as these must ever be liable to suspicion, there being no corroborative testimony in the shape of coins or similar articles. Saxon Swindon seems to have entirely disappeared; nor has Norman Swindon met with any better fate. Mediaeval Swindon, may, perhaps, in a certain sense, remain in a few scattered carvings of no importance, but even these are doubtful.

It was not until Thomas Goddard, Esq., of Upham, purchased the Swindon estate in 1560 that' the place emerged from obscurity. The Goddards then became the principal proprietors, and the leading family of the town, and have remained so ever sincethrough a period of three centuries.

Even during the Civil Wars Swindon seems to have in a general sense escaped notice.

Both the Parliamentary forces and those of the King must have marched within a few miles of the place, if they did not pass through; at any rate it is not improbable that a detachment came here. Just before the first battle of Newbury, which took place in 1644, the Earl of Essex fell back before the King from Tewkesbury, surprised a Royalist garrison at Cirencester, and, continues Lord Clarendon, the historian of the war: "From hence the Earl, having no farther apprehension of the king's horse, which he had no mind to encounter upon the open campagne, and being at the least twenty miles before him, by easy marches, that

his sick and wearied soldiers might overtake him, moved through that deep and enclosed country, North Wiltshire, his direct way to London," closely pursued by the King and Prince Rupert, who came up with the enemy about seven miles from Swindon, and an action ensued, which turned out in favour of the Royalists. If Swindon ever became the scene of civil contention it was probably when the two hostile armies passed by at such a small distance. Some few years since, while making excavations in the middle of Wood Street, just opposite Mr. Chandler's, the workmen came upon a number of human bones, amongst them a fine skull, which was preserved. A similar discovery was made in Cricklade Street.

These remains may have had some connection with those unhappy times when England was divided against itself, but of course this is no more than a conjecture.

Shortly after the Civil War came to an end, Aubrey, the Wiltshire antiquary, visited Swindon, and has left the following cursory memorandum of its condition at that date : "Swindon. This towne probably is so called, quasi Swine-Down, for it is situated on a hill or downe, as well as many other places, viz., Horseley, Cow-ton, Sheep-ton, etc., take their names from other animals. It is famous for the Quarrie, which is neer the Towne, of that excellent paveing stone, which is not inferior to the Purbec Grubbes, but whiter, and will take a little polish; they send it to London; it is a white stone; it was not discovered until about thirty years agon: and I am now writing in 1672: yet it lies not above 4 or 5 foot deep. Here is on Munday every weeke a gallant Market for Cattle which encreased to its now greatness upon the plague at Highworth, about 20 years since.

"Here, at Highworth, and so at Oxford, the poore people, etc., gather the cow-shorne in the meadows and pastures and mix it with hay, and strawe, and clap it against the walles for ollit; they say 'tis good ollit, i.e., fuell: they call it Compas, they meane I suppose, Compost. All the soil hereabout is a rich lome of a darke haire colour." It will be observed that Aubrey gives Swindon anything but a dignified origin.

Aubrey, however, is by no means an infallible authority. Though an earnest, painstaking, and often most intelligent antiquarian, he often displays a childishnessa gossiping disposition similar to that which made him labour so hard at the collection of ghost stories which led him to adopt the first thought that occurred, without investigation, and to take up time and paper, in recording little peculiarities, like that of the "cow-shorne," which would have been much more usefully expended in giving an account of the condition of the place itself. Swine are not fed as a rule upon downs;1 when herds of swine were kept their chief haunts were the forest,the boar's native homewhere acorns, beech masts, and roots, can be found in abundance. Nor, although in later times Swindon has become celebrated for its pig market, could such a circumstance be regarded as having given rise to its name, for the simple reason that the market was not held until the middle of the seventeenth century, and the place is registered as Swindon2 in Domesday Book, compiled towards the end of

|

1 Mr. Jackson also questions Aubrey's derivation: A down is not suitable for fattening swine. More likely named from some owner, a Saxon or Danish "Sweyne," a name still well known in the county.

2 Svindone or Svindune. |

the eleventh century. Aubrey was probably misled by the sound. Swindon certainly does bear an affinity to Swine-don, when pronounced with the i long. There does not appear any other ground whatever for the conjecture, nor can this ground be admitted. Sweyn-dune is a far more reasonable conjecture.

Even at that date it seems Swindon was famous for its quarries. The stone was even sent to London. It may be remarked that the spring of water known as the Wroughton spring, it being just out of the town on the Wroughton road, was discovered upon making some excavations in search of stone in the adjoining field; it is said not much over a century since. It is only necessary to take a glance at these quarries to see to what a wonderful extent they have been worked since their discovery some 200 years agoa good and indisputable testimony to the quality of the stone.

A few years back an interesting discovery to geologists was made in that quarry known as Tarrant's. It was a stem of a tree fossilized.

Scarcely a mantlepiece in the town that was not furnished forthwith with a piece of this fossil tree, so great was the curiosity awakened by the discovery, yet so much larger was the supply than the demand, that two large logs, if such an expression may be used, still remain in Mr.

Tarrant's yard, Sands, visible to all passers-by.

The "gallant Market" to which Aubrey refers, still continues to be held, though under very different auspices to those beneath which it was then conducted. A magnificent building now shelters corn dealers from the inclemencies of the weather, while in a short time cattle will be accommodated immediately without the town. It appears from these cursory notes of Aubrey that there was a cattle plague in the country to ruin and intimidate farmers two hundred years ago as well as now, or rather as two years since. The market was held on the same day then as nowMonday. This market owes its existence to Thomas Goddard, a descendant of the one who purchased the estate at Swindon in 1560. Thomas Goddard, Esq., obtained a charter1 to hold a weekly market, and two fairs yearly in 1627, which said markets and fairs have been duly observed since in the Square, Swindon. The custom to which

| 1 This charter was printed in the Swindon Advertiser, 12th September, 1859. |

Aubrey refers with respect to "cow-shorne"1 at Highworthif he means that it was used as fuelis remarkable in one way, since a somewhat similar one obtains in Palestine, according to travellersit might there be termed camel- shorne.

"What's one's bane is another's blessing," says the old proverb. The plague which harassed Highworth proved beneficial to Swindon, which seems to have escaped the ravages of the cattle disease as well in the seventeenth century as in the nineteenth. It would be interesting to learn the symptoms of that cattle disease which overran the country in the seventeenth century in order to compare it with that which so lately assumed so threatening an aspect. The market, established in 1627 by Thomas Goddard, Esq., was probably the making of Swindon. Henceforward it became indisputably a town. He seems to have been the only man in a course of eight centuries who showed anything approaching public spirit towards the place. The Goddard family very

| 1 Shard or shorn, by some thought to be the derivation of Shakespeare's " shard-born beetle " : i.e. bred in shard or dung [Macbeth] (Jackson). |

early had a connection of some sort with Swindon. The name is said to be found in deeds relating to the parish so far back as the year 1404over four centuries ago. They have been magistrates and members of Parliament for many generations.

The few preceding facts have been almost all that it has been found possible to gather, which in any way throw light upon the ancient state of Swindon. It is from them, and from their scarcity, very evident that the place was in old times of very little importance as a town.

These facts, however few and meagre, are, it is probable, all that will ever be found. Swindon, it must be recollected, never boasted a monastery, nor was it ever made into a corporate town. Many places which were once of importance sufficient to render a corporation necessarysuch as Wootton Bassettare now declining, or at a standstill, whilst Swindon, less favoured in days gone by, is rapidly expanding and developing its resources. Still, however modern may be its importance, a town that can date from before the Conquestback to the days of the Danes and the famous Sweyn, can never be despised in point of antiquity.

ALTHOUGH Swindon had no monastery, yet it had a church from the earliest times, known as Holyrood, or more familiarly spoken of as the "Old Church" to distinguish it from the new; for Holyrood, as a place of worship, is a thing of bygone days. The bells are silent, the belfry itself has disappeared, and of the body of the church, only the chancel and two ancient ivy-covered arches remain. There were no literary monks at Swindon in the mediaeval ages to leave behind them a curious chronicle for the learned of to-day to decipher letter by letter and sentence by sentence but there is the churchyard record with its ever-open pages, all saying the same thing, though in so many different ways; tombstones and tablets with many a tale of times gone by traced upon them. Here are no gaily-decorated manuscripts, but here is the handwriting of

death, and its emblazonry of cross-bones, urns, and praying figures. Not a step can be taken through this ancient churchyard that does not tread upon those who have lived and died, and disappeared; scarce a turf can be turned without bringing to light the melancholy and mouldering remains of mortality. Here the awful line of the poet Young is literally true

"Where is the dust that has not been alive?"

>p>Look at the rank, tall grass, damp even at noonday; its roots are nourished by that which once gaily trod the grass of its day under foot. Look at the dark green moss upon the tombstonesshortly it will fill up and hide the last memorial of those who lie beneath; others there are which have sunk out of sight in the same earth which received those they were intended to commemoratesuch is the end of man. Even the graven stone cannot perpetuate his memoryhe dies, and his place knows him no more. Verily this is the home of the dead. Why did our ancestors erect their sacred buildings so near their mansions? Here is the churchyard actually coming up to the very wall of the house. The same thing may be observed at Lydiard Tregoze, the seat of Lord Bolingbroke, where the church and the manor house almost touch. Probably priestly influence had something to do with itthe present generation would scarcely be gratified with the view of funerals being conducted beneath their very windows. To-day men appear to endeavour to become fearless of death by placing it out of sight, rather than by familiarising themselves with its accompanimentsprobably on the theory that familiarity breeds contempt. The appearance of Holyrood Church, so far as it is possible to judge from descriptions and drawings, must have been very venerable, though it had not the slightest pretension to architectural beauty. The tower, which was square and dwarfed, as if left unfinished, and much overgrown with ivy, stood at the western end and opposite the chancel. On the northern side was a kind of transept. The pillars which supported the nave are of a rather unusual shape, sexagonal. The two arches which remain have a very ancient appearance, increased by the ivy which encircles them. That portion which has been preserved is simply the chancel. It originally was in the possession of the Rolleston family, who were under an obligation to keep it in repair, but upon the demolition of the ancient edifice and the completion of Christ Churchthe present place of worship they transferred their rights to the new building, and the parish undertook the charge of maintaining the old church. The old church having been found inadequate to accommodate the constantly increasing population of Swindon, it was proposed to enlarge and restore it, and the committee appointed for that purpose had agreed to recommend to the parish the adoption of a design by the celebrated architect, Mr. Gilbert Scott, for that purpose. The late Mr. Goddard, however, offering a new site,1 and his son, Mr. A. L. Goddard, promising a donation2 towards the building, the parish, at a vestry meeting, decided to erect a new church on another site. The donation of Mr. Goddard formed the nucleus of a building fund, the liberality of the parishioners and the indefatigable exertions of the Rev, H. G. Baily, the vicar, among his friends, providing the remainder of

The total cost of the church was £8,000. Mr. Baily1 worked with great energy, and he had a large share in obtaining for his parish the beautiful edifice known as Christ Church.2 The Diocesan Society of that day refused any grant because the living was not in the patronage of the bishop, and the Incorporated Church Building Society were only able to give £130. The materials of the old church, save the chancel, which was preserved, were sold to assist the fund for erecting the new edifice. The bells (the tenor was cracked and re-cast) were removed to the new church, and are those now in the Parish Church. Holyrood was not the original designation of the church. In the fourteenth centuryand very early in it, 1302it was dedicated to St. Mary. About fifty years after this date, or in the year 1359, the vicarage was first endowed. The monastery of Wallingford had a certain interest in the place, the monks having a pension, which was taken out of the rectorial tithes. Before the dissolution of monasteries that great blow which was dealt in 1535 to the Roman Catholic religionthe Priory of St. Mary, Southwick, had the rectory. Hence it will be seen that although no monastery was ever in existence at Swindon, it had, through its church, connection with several of those great nurseries of the Catholic faith. The Abbey of Malmesbury, the Nunnery of Wilton, the Monastery of Ivychurch, near Sarum or Salisbury, the Monastery of Wallingford, and lastly the Priory of Southwick, had all, to a more or less degree, some interest in Swindon, whose ancient inhabitants were therefore doubtless well acquainted with the cowl and its customs. It may be remarked that after a lapse of many centuries the Catholic faith has once again begun to make headway in Swindon as well as in other localitiesthere being a Roman Catholic chapel in Bridge Street, New Swindon, which is quite a modern erection. England is beginning to feel the effects of universal tolerationa great problem which is working itself out around us, and has in America arrived at such startling developments.1

After the dissolution of the monasteries, the rectory fell, about the year 1560, into the hands of the Stephen family, then resident at Burderop. It continued in their hands until 1584, when it was purchased from them by the Vilett family. At least one distinguished man has been Vicar of Swindon. This was no less a person than Narcissus Marsh, who afterwards became Archbishop of Armagh.

1 This included ground for a new churchyard. 2 £100 the money.

1 The Rev. H. G. Baily, after nearly forty years' work in Swindon, accepted the Rectory of Lydiard Tregoze, in the gift of Lord Bolingbroke. 2 1850.

1 It must be remembered that this was written in 1867, soon after the Civil War.

| 1 Canon Jackson notes: " In the list of Vicars are three peculiar names Milo King, Aristotle Webbe, and Narcissus Marsh." |

| 2 Richard Jefferies himself appears the only literary man of note produced in this locality. (Ed.) |

| 3 In his interesting Swindon Fifty Years Ago, Mr. William Morris devotes two chapters to local "Worthies," amongst whom are Dr. G. A. Mantell, Mr. James Strange, William Pike, etc. But as, with the exception of Robert Sadler, they are literally local worthies, they need not be enumerated here, as Jefferies' statement is at present irrefutable. |

Holyrood Church must have seen some strange changes in that long course of five hundred years. Could the stones speak, what stories might they not tell of times gone by of armed men, of the knights who fought in the Wars of the Roses; later, of the quaintly cut beards and curiously slashed garments of Queen Elizabeth's reign; of the careless cavaliers of King Charles's days; of monks and mass superseded by surpliced clergymen and their comparatively modern service. The bells what changes they must have rung:

"For full five hundred years I've swung

In my old gray turret high,

And many a changing theme I've rung

As the time went stealing by "

might have been traced upon them. But the stones are dumb, save the records of the dead ; the bells are no longer heard, the belfry is down. The jackdaws have lost their building

place, though they still remain in numbers in the neighbourhood, and may be seen any day in the adjacent park. There was a very general feeling of regret when the old place was discovered to be doomed. "I have completed a monument more lasting than marble, more durable than brass," sang Horace on finishing a book, and his words have been fulfilled. So, though Holyrood has gone, there yet remains a record, slight and scanty, but still a record, written upon that apparently most perishable material, paper. Aubrey, who has already been referred to as visiting Swindon about two centuries ago, did not forget the church. Here is his memoranda concerning it: "Church. In the church is nothing observable left in the windowes except in the first, on the south side of the chancell, viz., the coate of Clare. This cross is on a tombe about a foote higher than the pavement on the north side of the aisle, belonging to------ Goddard, Esq. . . . In the same aisle, beneath his picture, was buried, aged 25, 1641, Thomas Goddard, Esq., husband of Jane, daughter to Edmund Fettiplace, Knight, his coate thus, Goddard (diagram). Somebody is buried by. I suppose his wife, but the inscription is not legible. This on an old freestone in the chancell, now worne out, Grubbe of Poterne (sinister). Also Stephens of Burthorp. The same in other colours and metalls.

Near this lye buried two children of William Levet, Esq. They were buried 1667.

"This under the altar, viz : "Here lieth the body of Thomas Vilett, Gent. He departed this life the 6th day of November, 1667. On both sides lye buried his two wives.' . . .

"At the upper end of the church this inscription: 'Christus, qui mortuus est ut per mortem suam superans mortem triumpharet, a mortuis ad vivos exsuscitabit. Buried the 5th of June, An. Dom. 1610, the body of Elenor Huchens, the wife of Thomas Huchens of Ricaston. Shee to this parish twenty pound gave to the relief of the poore, the use for ever. James Lord, and Henry Cus, her husbands, twenty pounds each of them gave to the poore of this parish, the use for ever.' "This in the chancell: 'Hic jacet Henricus Alworth in hac vicinia natus, qui adolescentiam in Schola Wintoniensi juventutem in Academia Oxoniensi senectutem in Patria Wiltoniensi, feliciter consecravit, ubique, castè, sobriè, piè, sibi parcus, suis, beneficus, egenis effusus, ab omnibus desideratus, Obijt XVI die Augusti 1669 Aetatis suae 75.' " The first remark that Aubrey makes is, that there was in his time but little left in the windowsby the use of which expression he would seem to intimate that there once had been something in them. Now the date at which he passed through Swindon was but a short time after the conclusion of the Civil War, and it is well known that the soldiers of Cromwell's army had a great fancy for smashing everything which in their diseased and heated imaginations they conceived to bear what was called "the mark of the beast," that is, to savour of Rome. Like the iconoclasts of the continent they had a mad hatred of anything approaching an image.

May it not then be reasonably conjectured that the Parliamentarian soldiers destroyed whatsoever they possibly could in a hasty visit to Swindonsuch as might have occurred when the army of Essex passed through North Wilts in 1644? Aubrey himself, if we remember aright, mentions in another part of his work that such had been their conduct at Bishopstone churchperhaps five miles from Swindonwhere they had smashed the stained glass, and left nothing for him to copy. Why may not the same thing have happened at Swindon? The windows themselves have gone since Aubrey's time, saving one which remains at the eastern extremity of the chancel, in which there is a little, but a very little, stained glass.1 It was the custom of the Roundheads to stable their horses in the old buildings which had once witnessed the celebration of mass it is to be hoped no such desecration ever occurred in Holyrood.

Aubrey observed the "coate of Clare," that is, the arms of that house, in the first window on the south side of the chancel. In the time of Edward I., about 1279, one Olivia Bassett, as has been already mentioned, held lands at Swindon ; and her grandson formed a matrimonial alliance with Eleanor, the co-heiress of

| 1 Jefferies here, somewhat inconsistently, gives credence to the current traditions of Roundhead irreverencethe Parliamentarian army acting as a convenient scapegoat for the sacrilegious acts of contemporaries. |

Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester, which perhaps may in some way throw light upon this "coate of Clare" which Aubrey saw.1 "Stephens of Burthorp would mean Stephens of Burderop. Burderop is understood, like Swindon, to have been named by the Danes, thorp being a Danish word for village. This lends strength to the supposition that Swindon was named from Sweyn, since it shows that the Danes had settlements in the neighbourhood. Leveltwo children of which name Aubrey found were buried here 1667is an ancient name, and persons of that designation long had some connection with the place. It is said that the name Levet or Leviet occurs in the Domesday Survey of Swindon. Alworth is also an ancient name, and one early found here. The Viletts then, as now, occupied the chancel. It may be observed that Aubrey gives no inscriptions whatever earlier than the century in which he livedthat is, dated before the commencement of the seventeenth century. Between 1600 and 1700 there are numerous interments commemorated with a tombstone and inscription, but earlier than

| 1 See chap, i., p. 14. |

that there does not appear to be any. Those that Aubrey copied, though ancient now, were most of them modern in his time, two hundred years ago, yet the church has been in existence full five hundred years. The truth would appear to be that it is only within the last two centuries and a half that Swindon has become the residence of persons wealthy enough to commemorate their losses by the aid of the engraver's expensive art. Such men as Odin the Chamberlain, the Bishop of Bayeux, the Earl of Pembroke, the Earl of Shaftesbury, the Talbots, and the Darells of Littlecot, no doubt had their family vaults elsewhere; and with the solitary exception of the "coate of Clare" not a memorial of the noble families once connected with Swindon seems to remain in the place. After 1560, when the estate came into the Goddard family, and the adjoining mansion became the residence of the owners, the church was made the sepulchre of persons whose memory was perpetuated by tombs and inscriptions.

The dimensions of the old church were as follows: The tower was in length 18 feet 2 inches, the nave 60 feet 1 inch, the chancel 31 feet 6 inches, altogether 109 feet 9 inches.

The breadth of the north aisle was 16 feet 5 inches, the nave 21 feet 5 inches, and the south aisle also 16 feet 5 inches, making a total breadth of 54 feet 3 inches, while the height of the nave was 30 feet. It was, therefore, a structure of some considerable size. The body of the church, which has now disappeared, contained a number of tablets, some near the pillars, others around the walls. Those adjacent to the three pillars of the south aisle were in memory of William Harding, 1821; Gulielim Home, 1730; Hannah Nobes, 1807; Rev.

John Neate, 1719; James Bradford, 1829; and the Rev. Edmund Goodenough, 1807. Upon and within the south wall of the church were affixed the following: To John Skull, 1755; Edmund Goddard, 1776; Joseph Randall, 1768; Millicent Neate, 1764; and Thomas Goddard Vilett, 1817. On or near to the pillars of the north aisle were originally affixed monuments to Elizabeth Slack, 1789; Rev.

John William Aubrey, 1806 ; Mary Broadway, 1747; Francis Miles, 1834; Richard Wayt, 1746; Ann Yorke, 1807; John Smith, 1775; and Henry Herring, 1767. Adjacent to the wall upon the north side were tablets to John Goddard, 1678; Richard Goddard, 1732; Ambrose Goddard, 1815; Gulielim Gallimore, 1697; Thomas Wayt, 1753; Hannse Tubb, 1756; and Elizabeth Evans, 1763. These were carefully removed upon the destruction of the building, and the majority of them are still to be seen preserved in the chancel.

The stone-paved walk from the Planks up to the chancel is in a great measure composed of gravestones. One may be observed upon the right hand immediately before the entrance, upon which there is cut a simple cross without inscription or date that can be seenwhich is perhaps even more suitable than a fulsome epitaph contradicting its own purpose by a superabundance of adjectives. The chancel is at present almost completely full of tablets and other monuments of the dead, many having been removed here from the body of the church. Over the high arched doorway within may be seen several gloomy hatchments, the monuments of departed greatness, with the usual inscriptions, such as "Resurgam." Against the wall leans the royal arms detached from its original position; while upon the elevation afforded by the steps which once approached the altar stand the unused reading- desk and carved communion table. The air is damp and cold, the light dim and gloomyit is silent, deserted, a fit resting-place for the dead, or for meditation. Here no longer is heard the voice of the warning preacher, no longer rises the hymn of thanksgiving, no longer is received the cup of commemoration; it is a place of tradition, the dwelling-place of the spirit of the past. A church must ever be a place of gloom to the majority of mankind, but a church which is deserted has its gloom deepened tenfold. It seems as though men had deserted that hope with which they formerly reinvigorated themselves within it.

At the east end, beneath the window, is the following inscription upon a stone let in even with the pavement: "Here lieth the body of Anne Vilett, wife of Thomas Vilett, gent., and daughter of Edmund Webb, of Rodbourne, Esqure, who departed this life December 6, 1643. Her age 54. She had living of eight children only one." The arrangement of the inscription upon this stone, as well as upon the two following, is peculiar, and at first sight hardly intelligible; the graver would seem to have been at a loss how to cut out what he was required without crowding, The stone close by has the following inscription: "Here lieth the body of Thomas Vilett, gent. Hee departed this life the 6th day of November 1667; also Captn. John, son of ye Sd. Ths.

Vilett, who died March ye 17, 1700, aged 70 years." The first part of this inscription is the same as that which Aubrey saw and copied when he visited this place two centuries since ; that relating to the son, Captain John, has been added since his time.

|

The third stone is in memory of Thomas Vilett's second wife, whose memory is preserved in these words: "Aug, 24, 1650, was buried Martha, second wife of Thomas Vilett, gent., and daughter of Thomas Goddard Esqure. She had three children livinge." All three of these stones, besides the inscriptions, have devices graven upon them. On the south wall of the church is a monument to three sisters: Mary, widow of John Broadway, late Vicar of this parish, died Jan. 7, 1747, Aged 70 leaving £20 yearly to the poor of the Parish; Dorothy Brind died 1748; (aged 64) and Margaret Brind died the same year (aged 68), leaving £100 to the poor of the parish. A tablet on the same wall records some benefactions, of the interest of £100, given by one Home; Joseph Cooper in 1790 gave some lands at Stratton St. Margaret, in lieu of and augmentation of the same. Near this is a very ancient and curious tablet which was seen and copied by Aubrey, but the peculiar spelling of which renders it sufficiently interesting to be copied verbatim. It runs thus: "Bvryed 5 of Ivne, the body of Elenor Hvchens the wife of Thomas Hvchens of Ricaston. Shee of this parish: 20 povnds gave to the releefe of the poor, the vse for ever. James Lorde and Henry Cvs her hvsbandt, 20 povnd each of them gave to the poor of this parish the vse for ever" (v. page 35). On the north wall there is a small tablet to the memory of Elizabeth Evans, dated 1763, which appears to have once stood in the body of the church. The inscription contains a memorandum of a rather singular gift, yet no doubt very acceptable to the recipients: "By her will bearing date IX day of May 1763 she bequeathed £50 to repair pews of this Church and also the interest of £70 to purchase six gowns to be given yearly in St Thomas' day to six poor women inhabitants of this parish, whose age shall exceed 60 years." The Vilett family appear to have occupied the chancel; the Goddard vaults are immediately without the remaining portion of the building, on the north side between it and the mansion. The number of interments is evident from the large space covered by the stones, one of which has graven upon it a curious figure, apparently of a person in a long robe, praying. The following is an inscription upon a tablet erected in 1838: "Near this place lie the remains of Ambrose Goddard, Esq., and of Sarah Marva, his wife. They lived nearly forty years in the adjacent mansion, happy in the love of each other, and in promoting the happiness of all around them, though severely tried by the loss of many of a numerous family. He represented the county of Wilts in Parliament 35 years, honestly and faithfully, seeking no reward but the testimony of his own conscience and the esteem of his constituents. His wife was highly gifted, and a bright example of Christian grace. They both endeavoured to serve God, by doing good to man. Through the merits of Christ may their services be accepted, and their happiness protracted in a blessed eternity." "A. Goddard, died June, 1815, S. M. Goddard, April, 1818. This tablet was erected by their few surviving children as a memorial of their gratitude and affection." The Goddards have now sat in Parliament over half a century. It has been remarked of the present head of that family that he is never absent when there is any likelihood of a division to require his vote. Their policy has ever been a consistent Conservatism. One of the tablets originally upon the north wall of the body of the church exhibited the following inscription: "Here lieth the body of John Goddard, gent, died December, 1678." This one may still be seen. It is in memory of John Vilett, Esqr.: "Deo optimo maximo. Hoc Sacravium instauravit et exoruavit Johannes Vilett armiger, a.d. 1736." Another was in memory of Thos. Smyth, D.D., died 1790, aged 86; of whom it was recorded that he was vicar of the parish; also to Mrs. Jane Smyth, who died in 1787 at the age of 74; they having lived happily together for a period of nearly half a century. But the most extraordinary monument is that in memory of one William Noad, and his four wives. Hannah, his first, died in 1733, aged 28 years; Hannah II., died in 1741, aged 29; Martha, the third, died 1766, at the age of 62; Ann, the fourth, died in 1776, aged 54 years; and finally, William Noad died himself in the year 1781, aged 70. This Noad, one might imagine, was a Mahommedan at least, since he managed to have the solacement of as many wives as is allowed by the Koran to the followers of the prophet, and a clever fellow, too, to steer clear of bigamy. Four wivesthis is the "Wife of Bath" reversed. If any one understood what matrimonial life is, one would think this Noad must have done so. What a pity he did not write his memoirs for the guidance of future husbands! He died at length at the allotted age of manthree score years and tenwhich fact shows what may be done in a lifetime. Noad must have known a good deal about womankind. His occupation in life was that of clerk of the parish. Altogether William Noad may be regarded as one of the most extraordinary men Swindon ever produced. It does not seem recorded that any such feat was ever performed before or after. Probably we shall never see his like again. Peace be to his ashes, for it is to be feared he had little during his lifetime. The office of clerk of the parish seems to have been for a long time hereditary in the Noad family. William Noad comes first, dying 1781; Henry Noad occupied the same post in 1752; another Henry Noad, in 1790, and a third Henry Noad vacated the office by death in 1848. This last Henry Noad is recorded to have held it for the extraordinary term of 57 years, or over half a century. What births, marriages, and deaths he must have recordedthe population of the place would in that time be almost entirely changed, a generation would pass away and another spring up, and he, clerk still, apparently stationary. The Noad family has been rather a remarkable one. The name is still known in Swindon. Cooper Noad, of Newport Street, makes good barrels, and challenges the world to produce better. All honour to the name of Noad! Swindon seems to be a remarkably healthy situation, since some of the inhabitants have reached ages which might fairly be put into comparison with those of more widely-renowned places. Henry Noad just referred to was clerk for 57 years, and there lie in Holyrood churchyard the remains of four persons, who, with another of the same, only lately [1867], deceased, have not inaptly been designated the Five Patriarchs. The name of this remarkable assemblage of aged persons was Weekes. Thomas Weekes died in 1829, at the age of 91 years. Hannah Weekes, who departed this life in 1826, reached 82. Ed. Weekes, died 1821, aged 83. Susan in 1820, also 83 years of age; while John Weekes, died 1866, reached the truly patriarchal age of 92 years. The sum of the lives of these five personsall of whom, let it be observed, have died in the nineteenth century, and therefore it cannot be supposed that the virtue of Swindon air was better in the olden times than nowthe sum amounts to 433 years! Eighty and six years was the average age of this remarkable family. Nor are they single examples of the remarkable longevity attained by the inhabitants of Swindon. A lady of the name of Read (deceased during the present year) was, if we remember rightly, 91 years of age. Her remains were interred at Wroughton. Mr. Shepherd, still living [1867], is another example his age is 90. Mr. J. Jefferies has reached his eighty- fourth year. On the whole, Swindon can furnish examples of longevity which may challenge, if not defy, competition. |

WHENEVER a man imbued with republican politics and progressionist views, ascends the platform and delivers an oration, it is a safe wager that he makes some allusion at least to Chicago, the famous mushroom city of the United States, which sprang up in a night, and thirty years ago consisted of a dozen miserable fishermen's huts, and now counts over two hundred thousand inhabitants.

Chicago! Chicago! look at Chicago! and see in its development the vigour which invariably follows republican institutions. This is confounding the effect with the cause. The hundreds of thousands of American emigrants

| 1 Readers are reminded that this chapter has been left as Jefferies wrote it, as, if it had been brought up to date, much of the original matter must have been omitted as obsolete; whereas the details of thirty years ago are already old enough to be interesting to the historian of the town. |

must have something to do, and somewhere to live. Men need not go so far from their own doors to see another instance of rapid expansion and development which has taken place under a monarchical government. The Swindon of to-day is almost ridiculously disproportioned to the Swindon of forty years ago.1 Houses have sprung up as if by enchantment, trade has increased; places of worship seem constantly building to accommodate the ever growing population; as for public-houses, they seem without number. A whole town has sprung into existence. The expression New Town is literally true. It is new in every sense of the word. New in itself, new in the description of its inhabitants. There was no republican form of self-government at Swindon forty years ago on the contrary, the place was decidedly conservative, averse to change, and looking at those who proposed it with suspicion. It certainly was not owing to republicanism that the place developed so fast.

That was not the cause, but that has been the effect. New Swindon is as decidedly demo-

| 1 Middlesborough is another famous example of the rapid growth of an English town. |

cratic in its sentiments as Old Swindon was conservative. The real cause of this enormous development may be traced to that agent which has effected an almost universal change Steam. Swindon is going ahead by steam the phrase is literally and metaphorically correct. Yet the first push was not due to steam. Forty-five years ago, or thereabouts, the Wilts and Berks Canal came along close below the Old Town, cutting right through that flat meadow-land which was, twenty years after, to resound with the hum of men.

The calm, contemplative, chew-a-straw steersman of the barge boats was then first seen slowly gliding past, tugged along by a horse walking on the tow-path. With what amazement and admiration the agricultural labourer's children must have been struck as they viewed the progress of the painted boat; how they must have envied such an apparently easy life! These children were designed to see more astonishing things yet. Simple as they were, they have seen in actual existence what the wise men of former ages never dreamt of.

That part which it was found necessary for the canal to pass through immediately beneath

Swindon was discovered to be the highest level on its whole course. Here there was no necessity for a lock for a distance of seven miles, and accordingly there is, at this day, a clear stretch of seven miles of waterNew Swindon being situated somewhere about the middle, and consequently, a capital place to launch pleasure boats could the Canal Company be persuaded to speculate, or allow others to. A canal was something so utterly foreign in its conception to what the country people had been accustomed, that it was dubbed the "river," and goes by that name in the country round to this day. This long stretch of clear seven miles without a lock necessarily intercepted and received the water of numerous streams and rivulets, whichthe right of use for certain periods of the year having been purchased by the Companyare used by them to keep this portion of the canal well filled, in order to supply the loss when a lock is opened. But so great was the traffic in those days, and accordingly so great was the quantity of water required, that it was discovered that in the summer, should it chance to be a dry one, there would always be the risk of a deficiency. Moreover, a lock might break, a bank might slipa hundred possible accidents rendered a constant reservoir at this, the highest level desirable, and indeed necessary to the proper working of the canal.

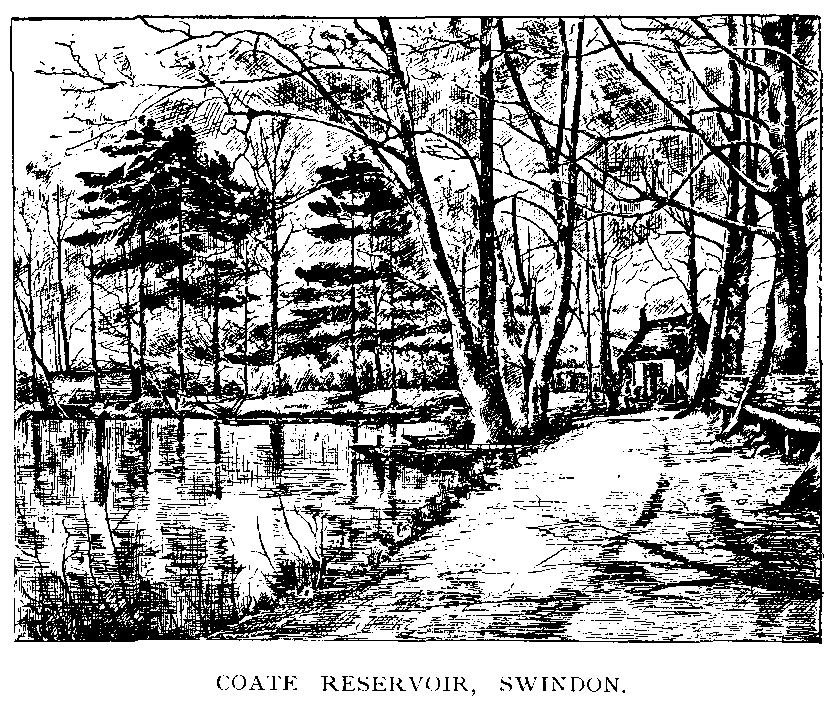

Accordingly the engineers of the Company cast about to find a fit place to construct a reservoir, and at last fixed on a valley at Coate, about a mile and a half from Swindon.

This valley was enclosed by a bank at each extremity, and the water of a brook which originally ran through it, together with that from other springs artificially compelled to run here, being allowed to accumulate, formed exactly what was desired; while the original course of the brook took off any superfluity that might occur from flooding, and by a branch from it the canal could be always supplied. But the site offered one difficulty.

There was a spring rising immediately without the upper bank of the reservoir, which it was found impossible to make run into it; moreover, it was wanted by the farmers and inhabitants of the vale beneath. This, then, must run under the reservoir. A brick culvert was accordingly constructed, but an unfortunate oversight occurred. That part of the bottom of the reservoir over which it was necessary the culvert should be carried at the latter end of its course, had originally been but one remove from a morass, in short, was very "shaky." Upon this unstable foundation the culvert seems to have been placed, and with the result which might have been anticipated.

The weight of the brickwork, with a superincumbent load of earth and sand thrown on, proved too great for the soft ooze upon which it was placed. The culvert gradually sank in places, the brickwork cracked, and leaks have ever since been more or less frequent. One occurred of a very serious character, when the meadows below were flooded by the escaped water of the reservoir, and had not a hatch been beaten down by sledge hammers, it has been thought that the reservoir bank must have been washed away, and the thousands of tons of water it contained would have been precipitated into the vale, the effect of which would have been an enormous damage to property and probable loss of life. The reservoir, when full, covers an extent of seventy-two acres, and is a favourite place for summer pic-

nics, being so near the town. Racing boats were formerly kept here, and some exciting pulls occurred, but this has long been discontinued. The want of boatsthose that there are being utterly insufficient to supply the demandcauses much remark, since they would evidently be a paying speculation.1 It is a beautiful sheet of water, approaching a mile in length, and has so much the appearance of being natural, that it is difficult even upon examination to consider it a work of man.

The delusion is kept up by the numerous trees, and the romantic scenery around. The place was completed in 1822.

The completion of the canala wharf being of course constructed opposite Swindongave the first noticeable stimulus to the progress of the place. Swindon was a kind of junction, the canal here branching off into twoone going to Bristol, the other to Gloucesterand consequently a most favourable situation for trade. Coal now reached the town in greater quantities, and at a much less cost than previously, and a great carrying trade sprang up.

Old inhabitants relate that in winter, when a

| 1 This defect has long since been remedied. |

sharp frostsomehow the frosty weather in these modern days never seems to come up to the description of that of yorehad bound the canal as if with iron, there was immediately an apprehension that the price of coals would rise; which, if the frost continued, and the barges could not come up, it accordingly did, until all that remained upon the wharf being consumed, a coal famine would ensue. Enterprising farmers, whose teams could not work in that weather, would then dispatch a waggon and a trusty man even down to the very pit's mouth, purchase a load cheap, and make a good profit by retailing it around. These were the good old days! The poor must have suffered grievously for want of fuel when even the wealthy were straitened, especially in town, for in the country districts wood was plentiful, and the fireplaces adapted for consuming it.

These were the halcyon days of the Canal Company. But a new wonder was to come and supplant the old.

Those who could afford to purchase a paper (for papers were not sold for half-pence then) and who could read it when they got it, had already been wondering over what would come of that new inventionthe steam engine. It answered well to pump the water out of the mines in Cornwall, boats had been propelled by it, and finally, a tramway was constructed at Manchester, which was found successful.

Then began the mania of railway speculation, which, if it ruined thousands, proved the basis upon which Swindon was to rise. The idea of the Great Western Railway was at last started a gigantic scheme which was to connect the two great cities of the South of England, London and Bristol, by a level iron road.

Men were seen about in all directions, with curious instruments, to the wonder of gaping rustics, and the rage of farmers whose hedges had gaps cut in them to clear the line of sight, or whose property was trespassed upon by enterprising engineers. The plan was looked upon as monstrous by the aristocracy of the country. These iron roadswho could hunt if they intersected the land ? These screaming engineswhere could be found a quiet corner for the pheasants, if they were allowed to roam across the country ? Good-bye to the rural retirement and peaceful silence of the deer- dotted park, if once the white puff of the steam engine curled over the ancient oaks! Great opposition was offered to the railway bills, but they were passed in spite of all, with a proviso preserving parks; which, by the way, diverted the Great Western from running immediately by Old Swindon, it having been originally designed to pass somewhere about where the gasometer stands now, that is to say, to intrude on the Goddard property.

The work was now vigorously proceeded with. On the 26th of November, 1835, the first contract was taken. This was the Wharncliffe viaduct. Excepting about four miles in the vicinity of London, the rest was let out down to Maidenhead, during the following six months. The work of the Bristol part was commenced in 1836, and the first contract let was a length of nearly three miles, extending from the Avon to Keynsham. But the most formidable undertaking on the whole line was the celebrated Box tunnel. The shafts were contracted for in the latter part of 1836, the tunnel itself in the following year. Three long years were expended in drillingif such an expression may be employedthis enormous hole through the hill; it having not been completed until 1841. The depth which the shafts had to be sunk was on an average 240 feet, and their diameter is twenty-eight feet.

The tunnel is straight as a gun barrel, and can be seen through from end to end, which allows the observation of some singular effects of perspective. Its length is 3,200 yards, or nearly two miles; it cost over half a million; no less than 20,000,000 of bricks were employed in the construction of the arching. The whole length of the line from Paddington to Bristol is 118_ miles, and it was completed in the following order:Maidenhead opened up to, on June 4, 1838; Twyford, July 1,1 1839; Reading, March 30, 18402; Steventon, June 1, 1840; Faringdon Road, July 20, 1840; Bristol to Bath, August 31, 1840; Wootton Bassett Road, December 17,3 1840; Chippenham, May 31,4 1841; to Bath, June 30, 1841. That part of the line which runs past Swindon is for several miles remarkably straight. Approaching Swindon from London, the rail is carried through a deep cutting, especially near Stratton St. Margaret; but upon the other side

| 1 Or 5th. |

| 2 Another date is 6th April. |

| 3 Or 16th. |

| 4 Or 1st June. |

it is raised upon an embankment. Much of the earth of the embankment was taken from a field on the slope of Kingshill Hill, at the top of the Sands, Swindon; the soil being purchased, of course, from the owner for that purpose. A tramway was constructed in such a manner that the trucks running down the hill drew up a string of empty onesa simple but dangerous proceeding which gave rise to one accident at least. It is to the railway that Swindon owes its importance, and New Swindon its existence. Swindon now became the emporium of North Wilts and the adjacent counties. When it became a junction, and all trains were ordered to stop here ten minutes, it derived additional importance, and became a place well-known to travellers. The station is itself a fine building, and contains some large refreshment rooms.