Appendix 1

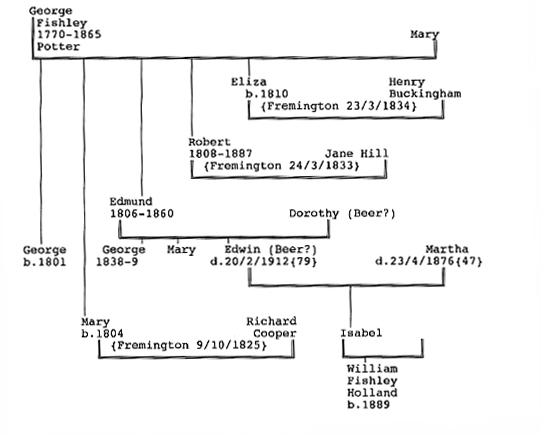

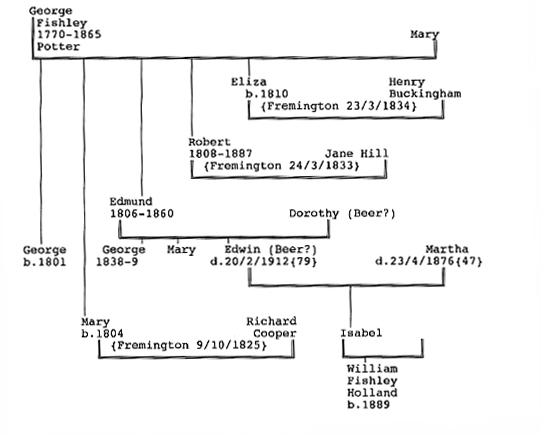

William Fishley Holland was born in Yelland, Fremington, North Devon, in 1889. He was the fifth of a line of peasant potters stretching back to George Fishley. His mother was Isabel Fishley, daughter of Edwin Beer Fishley. He was one of five children, three daughters, two sons. His father died when he was five years old.

At the age of 12 he passed a Labour Certificate Examination and left school. A year later his grandmother became an invalid and his mother had to go to Fremington pottery to look after her.

Extracts from "50 years a potter" by W Fishley Holland published by Pottery Quarterly of 1958.

Fremington Pottery was the last place where the true Devonshire traditions were carried on up to the time I left it, in 1912, a year after the death of my grandfather, the late Edwin Beer Fishley; and he had inherited them from his grandfather, George Fishley, who was born in 1771 and died in 1865.

George Fishley 1770-1865

Edmund Fishley 1806-1860

Robert Fishley 1808-1887

Edwin Beer Fishley 1832-1912

The small pottery..... probably employed a dozen or more in the times when red earthenware was in great demand for all household purposes; for cooking, containing food and water; ovens for baking bread, drainpipes for farmers, a few rough bricks and the old fashioned pantile; flowerpots and in fact anything that could be made of clay.

When I came to join my grandfather, in 1900, there were four men, besides he, his cousin, John Beer, and myself; each having his own particular job. Grandfather did most of the throwing and an old man of seventy turned the wheel.

One made the bread ovens, pantiles, pipes, bricks, etc. Another drove the horse which pugged the clay and carted the pots to market and customers in neighbouring towns and villages. The wagoner helped with the farmwork too, for we grew our own corn, potatoes and food for the horse. How self supporting and independent we were and how full our life! When the old buildings were in existence it was a most interesting place, as one could see how it had developed, by the styles of the various chambers. The kiln was, of course, the first thing to be erected, and it was built into the slight slope of the yard. This meant that some of the rooms were on the ground level, as were the fireholes; then there was a slipway leading up to the kiln doorway and a series of chambers on the same level. These had been built at various times as they were needed and as they could be afforded, and their styles and construction always intrigued me.

They took rough poles and put the ends into holes in the walls, fairly close together, then straw was spread over them, and two planks side by side made the runway. On this we walked as we carried the pots from the kiln to be stored in the bays along the chambers. During the course of time, the dust had covered the floors, until they looked solid, but it was a springy walk. The bays were made of poles of smaller sizes.

The windows were just a hole framed with wood and there were a few shelves made of similar poles. I have never seen anything more primitive yet so entirely suitable for its purpose. Down in the workroooms the walls were of the same construction, but here and there hand made rough bricks formed the doorways and windows and iron rods were used instead of wooden battens to hang the pantiles to lessen fire risk. The smoke of ages had covered everything with a treacly coating which did not seem to be inflammable, and it hung like stalactites from the roof. All floors were of natural earth, worn hard with the tramping of feet.

The walls surrounding the storage place, or 'clayain', were made of large pebbles from Westward Ho. These kept the clay clean and free from lime, which has a deleterious effect if present in firing. Those old potters certainly knew their job and also how to use the things they found at hand.

The only thing we got from afar was small coal for firing and galena, or lead ore, and a little ground flint. Old baking ovens which had cracked in firing were upended to hold water for damping down the fires on kilning days. Some of them had been built into the immense walls which formed the base of the kiln, which seems to prove that there had been a pottery previously at Muddlebridge. Wherever you went round the place it was quaint and interesting and told its own story. My grandfather had built a wheelhouse and drying chamber adjoining the road, but all the rest was as old as the house. I should say the adjoining small cottage was there at an earlier date and that in it Robert Fishley had lived, but it was uninhabitable in my time.

The bay into which the wagon was backed for loading from the ware chambers, also the stables, cart shed, pigsty and cow house, were on yard level. We kept pigs but no cow at this time. Earlier it had been the custom to keep both and the dairy was well equipped. A large vine covered the tiled roof at the back of the house, from which some splendid wine was made. We kept hens and had a fine garden, tilled by the men, with plenty of fruits, rhubarb and seakale.

It was in 1902, when I was thirteen, that I came to Fremington Pottery. Since one had to be fourteen before being allowed to work in any workshop or factory, I spent my time helping on any job that I felt I could do; and if anybody turned up who looked like a Factory Inspector (through they seldom came to the pottery) I kept out of sight.

My living had to be considered and I well remember the day I was called to my grandmother's bedroom and she asked me if I would like to become a potter. I had already become quite interested in all the processes, so decided in the affirmative. I did not realise then that it was a dying industry. I was told that grandfather would fit me out with clothes, boots, etc., and pay me half a crown a week together with my board. I though my fortune made... half a crown a week all my very own! For a few weeks I saved and managed to amass three half crowns, which were kept in a little wooden box given to me by a wood turner in Barnstaple.

As soon as I became fourteen I visited the doctor and was passed as fit and strong enough to become a potter. First I had to learn to make flowerpots, starting with 3¼ inch, which had to be made larger to allow for shrinkage. This was the most popular size used by the nurseries and was in greatest demand. We learnt on a kick wheel and had to watch whoever was on the 'big' wheel- turned by a man- and try to imitate what we saw. This wheel was about two feet in diameter and was driven by a belt from a large one about the size of a cartwheel situated some fifteen feet away.

Old Tom turned it. The commands were, 'turn', 'steady' and he was supposed to know exactly when to slow down as the larger pieces grew, when to go fast for centring the ball and when to stop as he saw the wire cutting off the pot ready for removal. Many a time have I seen old Tom turning whilst asleep, especially when small things were being made, as the wheel would then be kept going until the board was full.

The hours we worked and some of the strange customs should be recorded. We started at 6.30 a.m., stopped at eight for half an hour for breakfast, then worked till eleven, when we had the half hour lunch break. It was a tradition with the Fishleys to have a cooked meal then, and at one o'clock nothing but a cup of tea or coffee. Being a growing lad, I always wanted another good meal, much to my mother's disgust. We then worked till six in summer. As the days got shorter we stopped work when we could no longer see. There was no artificial light in the pottery, but each of us had a little oil lamp with a single wick, but no glass, and this gave just enough light for working among the pots in the drying rooms, which, being enclosed, were absolutely dark.

In the dead of winter we would be finishing at 4.30. On Saturdays we had no dinner hour and worked through till four o'clock; that always seemed a long day to me.

On Fridays grandfather always attended Barnstaple market. John Beer kept the stall there, selling milk pans, pitchers, etc.

Grandfather kept a pig and, in season, John Beer did the killing. I helped and simply detested it. But he was very proficient, and the resulting pork was always appreciated; and as to the home cured joints and bacon- well, nothing tastes so nice now! Many men outside the butchery trade could kill and cut up a pig proficiently in those days. They took pride in anything they tackled and were versatile too.

We tended the large garden and marketed the produce wholesale. The produce would be fetched by an old man from the workhouse with a donkey and cart. We grew corn and mangolds for the horse, potatoes for the family and the pigs, made and thatched ricks, tying the corn by hand.

Nothing was wasted. If the clay got dirty, it was made into bricks for building fireplaces. For this we mixed ashes to open it up, Fremington clay being much too fine in texture otherwise. To get our gravel, barges went above Bideford Bridge, and worked the tides so that they got to Muddlebridge on the next high tide to unload. When Bideford pottery was working they loaded back with clay. The barge hands did not get much sleep then. All this has long ceased, as well as shipping of pots from Fremington to Cornwall, but the remains of Fishley Quay still may be seen.

It is interesting to look at the reasons for changes in any craft and as I lived through those in potting, I can speak from much experience. Oven making was once a flourishing business, as the cottager had only this means of baking. There were no iron ranges or stoves- only hearth fires; and on these the women did their own baking, using barm, obtained from the local pub, for leavening. This meant keeping a barm jar, which had a bung in the top. I remember Philip Taylor's baker's cart with the words 'Best Barm Bread' on it, also the coming of the yeast stall to Barnstaple market. In towns, people sent their dinners to the local bake house to be cooked after the baker had done his batch of bread. I often saw this at Appledore.

Pigs were fed from terra-cotta troughs and salted down in our salters. Cottages and villages had their wells and pumps, and so required pitchers. Milk was kept in them too after being fetched from the farms. About a hundred years ago the potter was in great demand, together with the wood turner, but the coming of cast iron, the galvanised and later, enamelware, piped water and other amenities entirely changed all that. There was little demand for what is known as slipware of the more ornate kind, as few people had any artistic taste- even if they could afford the ware.

It was when many of these changes were taking place that I came to Fremington. We kept on a steady trade right up to my grandfather's death in 1912, but prices had not risen for many years, so there was little profit in potting.

With all these changes, we naturally had to look for other markets so grandfather made bedroom sets, beakers, jardinieres, tankards, bowls, jugs and some loving cups and tygs in coloured pottery and slipware. He was a good draughtsman and was commissioned to make some Etruscan type vases with sgraffito decoration. Some of these were at the pottery until his death, when they were distributed among his children. Although the demand was not great, he had a few friends who appreciated the quality of his work and they held him in high esteem. His work was entirely different from the earlier Toft type of ware which his ancestors made. Red lead was used instead of galena for glazing, and it was not fired in saggars. This was the secret of the variety and beauty obtained, as the pots got alternate oxidisation and reduction and often came from the kiln with most interesting lustre and bloom. His shapes too were perfect, because, where some potters used a tool, he used his fingers to finish tops of jugs and got a much better line. In those days, there was not the variety of colours and glazes and frits available, and we relied on coarse ground copper, cobalt and iron oxides, which we ground with pestle and mortar. This gave us varied textures and, I think, more interesting.

The warmth of the place on winter mornings at 6.30 was most acceptable. When there was severe frost and lots of pots about in the green state- that is, raw clay- we used what we called a devil, the sort of thing one sees being used by night watchmen. We would mix a pan of wet clay to a barrowful of small coal, tread it well and make it into balls the size and shape of a goose egg. These, placed in piles with a piece of sheet iron on top, on the draughty side, would make smoke and heat enough to keep off the frost which wet pots seem to attract. How different was the sulphurous fume of the devil from the sweet smelling wood smoke!

When the chambers were filled with dried pots, John would walk round and take a mental picture of everything; and when he was satisfied that there was sufficient, we went to the kiln. Two men brought pots to the kiln door, and one handed them to John; but it took four to handle ovens. For pans of various sizes, the rings were handed in and we packed up to the doorway level. The kiln was about four feet deep. We started with tiers all round the sides to the required height. Having filled the middle, we partly bricked up the doorway. Next day, I had to stand on a plank in the middle of the kiln and hand everything to John until he got near enough to the door to reach it himself.

Everything had to be carefully thought out in building this jigsaw of pots. I tended John, to learn how to finish the job. The doorway was then bricked up and plastered with a mortar of sand and clay to prevent air from entering during firing. The time came when John, getting old and rheumaticky, was often unable to work. Then grandfather asked me if I could pack the kiln. How I enjoyed that responsibility! I had been packing a day or two when John came along; and although I had planned everything, I asked him how I should proceed. He was so pleased that he recalled the incident several years after on his deathbed. He said to his daughter: 'One thing about Willie was he was never above being told.' I like to remember this. John and I were always very good friends, and I owe a lot to his excellent teaching. I still remember him as I do the jobs we so often did together. It is through him I know most about my ancestors, as he would relate stories of his boyhood as we worked. His parents had died when he was very young, and he was brought up with my grandfather, his cousin, at the pottery. He always did the fettling and finishing side, whereas grandfather was a thrower chiefly.

John packed the last ships that took the pots to Cornwall. The coming of railways brought this to a close, as it did most of the North Devon shipping. I have seen seventy ships sailing over Bideford Bar when they have been held up by bad weather, or after they had been home for Christmas. The sight of those ships tied up four abreast alongside Appledore Quay is something that will never be seen again.

Firing days at Fremington were busy and exciting. The kiln was 'soaked' overnight with a coal fire much slowed by a covering of cinders and a little ash. Bill Short came at six thirty in the morning to lay and light the fires which he then tended all day until 11 p.m. How's that for a day's work, ye moderns? Grandfather, even when over seventy, used to take on from then till 3 a.m. My mother suggested that I should do this turn, so I asked Bill to show me how to fire. Then I asked grandfather to go to bed; and, after watching me for some time he allowed me to continue. Afterwards I always did this turn. John Beer came at 3 a.m. and worked till we had finished- sometimes as early as 12.30, but I have known a stubborn kiln to take until 3.30. We all finished when the fireplaces had been sealed. Nobody complained about the hours being long, but I found the time dragged and the clock seemed to stand still during the nights. One seems to require much more sleep at that age than I got. John's footsteps always sounded most welcome.

Three days later, we knew the result, and it was a recognised day's work for three men to empty the kiln and carry everything to its place in the chamber.

From my experience of kilns, it is evident that every potter used his own judgement in the size and pattern he built, which meant that each knew the peculiarities of his firing. They built them themselves, so they were well acquainted with them by knowledge gained by trial and error and passed on from father to son- never forgetting the team spirit.

At Fremington we still had the iron trough and pounders with which they pounded the lead ore a generation before. Both grandfather and John had seen this done, and they told how men got belly ache and called it colic, which was probably due to the dust from the lead. Grandfather had built a small kiln, about six feet in diameter, which was planned for a down draught and had a chimney about ten feet away. It did not answer, so they converted it to an up draught just as I joined them, and I had the experience of testing it. I can now see where they had gone wrong- by having the fireplaces too deep, their idea being to mellow the flames before they reached the ware. It was with this kiln that I had a memorable experience. One summer night I lay on a six inch plank, half open to the stars, and must have slept for about two hours. When I woke the fires were almost out and the fireplaces cold. Although I bustled round and got them going by the time John came they were very much behind and I had to explain what had happened. The kiln was late next day, but grandfather never mentioned it to me, so I think John again shielded me. When the pots came from the kiln, there were some basins for bedroom sets in biscuit at the top and they were all marked with a crocodile skin pattern. The slip had chilled and pulled back. When these came from the glaze kiln they were most unusual and beautiful and sold at a higher price because they were unique.

When visiting Ray Finch's pottery at Winchcombe, which he took over from Michael Cardew, I was shown some pinch gut pitchers which he told me came from Fremington and were made by my grandfather, whose photo he had. He was greatly surprised to know that I made them and that John had bowed them.

I had still to find out the way to glaze the finer pots which grandfather made. Unfortunately he died before I had accomplished all this. In his desk was a very old book in which he had written some of his early experiments. I studied this and eventually found an interesting entry showing how he had tried various ingredients in different quantities. Alongside he had commented thus: good, very dry, fair, best. I was able to gather some useful information, but I did not know what all the symbols meant. I lacked the key. However, it was not long before I discovered the secret and much else besides in connection with grandfather's glazes, although I had to go a long way round to get there. With some help from John, who knew where everything was kept, I eventually made a trial, but it was wrong. One night I had a vivid dream in which I saw the hiding place of the key, and, relating this to my daytime experience, I have always considered the key to have been itself locked up in John's mind. Grandfather used red lead, flint and stone, the most successful trial having two parts red lead to one each of flint and Cornish stone. I have since found that a little china clay improves the glaze. This makes a good transparent glaze, but if black oxide of copper is added in various proportions, some brilliant greens, running right through to a blackish lustre, are obtained. This was on a red body, fired up to 1,000°_C. We used this base for most of our glazes for many years, but we now use a Lead Bisilicate. If we wanted a matt effect, we increased the china clay and flint, as the lead is the flux and in too great quantities gives crazing.

The great thing in pottery is to observe the peculiarities of any particular glaze and to make use of them. Grandfather's yellows made with red oxide of iron, sometimes nearly an ounce to the pound, were beautifully full and varied. This glaze needed to be put on thicker; otherwise, due to the iron, it had a starved appearance. Violets from manganese were less popular, though I thought them extremely pleasing. Fashions change and there is usually one colour which sells better than others for a period. I well remember when matt glazes became fashionable and one of my fellow potters simply added enough hardening ingredients to dry his glaze to a very dull and, I thought, uninteresting finish. It sold well for a time- till people found that it held the dust. It was no use offering shopkeepers anything bright, they just would not look at it.

My thoughts go back to the many interesting little events that used to make up our daily life and how we enjoyed them. Each of us took a personal interest in the detail of the job in hand, so that our lives seemed full and happy. We would sing at our work whenever possible, and the songs of our day were more melodious and had a longer life than the jazzy stuff of this age.

We had the hurdy-gurdy paying regular visits and knew the tunes by heart. When a new type came with what sounded like a mandolin accompaniment we thought it perfect. This music coming across the valley from Muddlebridge House will always remain in my memory. When I was a small boy, the hurdy-gurdy business was in the hands of Italians. Each week they came to our farm and always received milk and three pence. They became real old friends. They had a cage with budgerigars. For a penny, the birds would be taken out on a stick and would pick a card with your fortune from a drawer attached to the cage, much to the enjoyment of us children.

Another character was a tiny man named Robins but, of course, called 'Cocky'. He was one of the early cyclists and on a Sunday would call on my mother for his 'usual'. She would cut a slice of her own baked bread and pass it under the cream standing in the pan. It made a nutritious meal for three pence. There would not be many cyclists today with roads as they were then- rough and stony and inches thick with dust, which became a slurry mud as soon as it rained. It was a problem to keep footwear clean. There were no easy shining polishes, only cakes of 'Berry's Blacking'.

There were one or two motor cars in our district. One came from Westward Ho to Barnstaple frequently with ladies seated high behind a uniformed chauffeur and with their heads encased in a veil attached to a wide brimmed hat. The doctor's car was T4, one of the earliest Devonshire registrations. When one of these went along the road on a dry day it was followed by a tremendous cloud of dust and anyone passing could scarcely breathe. When the steam roller had been making up a piece of road we thought it marvellous, but the iron tyres of the horse drawn wagons soon made ruts again. Road men with shovels for loading stone, rakes for pulling them back into the ruts and a mud rake for wet days were a common sight. We have to thank Macadam for a lot.

A carrier's van was our only means of transport. One came from Bideford to Barnstaple, another from Barnstaple to Bideford and either would bring our requirements from town for a copper or two. Often the carrier would be the worse for liquor by the time he reached us. He had many more miles to go and more pubs to visit. Beer was cheap (2d a pint) and strong, and he seemed to thrive on it. The horse would take him home. I was a choirboy and had to ride nearly two miles with him. Winter nights caused me some anxiety, as we could only tell where we were by the rise and fall of the road and Bill was too sleepy to keep watch.

Country lads passed their time by visiting each other's stables, where they cleaned brasses, of which they were very proud, to decorate their teams of beautiful cart horses. They also busied themselves with cleaning and repairing harness, plaiting horses' manes and tails and generally caring for their well being. One of my mother's farm hands was quite good at doing quick sketches with chalk, and he would entertain us with his efforts on the wooden panels in the stable. Another could play all the song and dance tunes on the old fashioned accordion, a much smaller and simpler instrument than the organ like contraption we see today.

I think that in those days many more boys played such instruments. The mouth organ was extremely popular and often played with great skill. Straw plaiting, leatherwork, shoe repairing and other crafts were considered part of one's natural education. Step dancing on a special board, to the music of one of the company, passed away many a happy hour. We would go to each other's stables and spend the evening making our own fun.

For some weeks before Christmas, a few of us would get together and form a minstrel party and practice our various items in readiness. An accordion, tambourine, tin whistle, home made drum, cymbals, bones and of course the step dancer with his board. We knew which farms were holding parties, and after a tune up outside we were asked in to entertain, then given a good meal and some cider or whatever we wished to drink. All wore minstrel costumes made by our womenfolk with our help. Tin buttons were fairly easy to cut and big white collars were made from cardboard covered with linen. Faces were blackened with burnt cork. It was usually possible to find an old top hat, so we looked quite professional. The farmers thoroughly enjoyed our musical efforts, and we got great fun out of it as well as a few most useful shillings. Looking back, I should say that we were by no means lazy or devoid of imagination. By the time we had finished our rounds, all had spent a happy Christmas and New Year.

It was the custom of leaders of church life to organise plays, concerts and dances, and a team could generally be found who could give a creditable performance. Only on very special occasions did we have a piano, fiddle and drum band. The old accordion player would carry on through a night's dancing for three shillings and the boys and girls (yes, and the older folk too) entered in with great zest.

Election time was taken seriously. We had torch light processions for the various candidates and would sometimes take out the horses and draw their carriages by hand from village to village. Special political songs were sung to the popular tunes of the day, and we walked miles some nights. Next day we entertained each other with tales of our experiences, and the time passed merrily. My people on my father's side were yeomen farmers and Conservative in politics. I once heard my grandfather Fishley say he had voted Liberal only once and always regretted it. Socialism was unheard of but Liberalism was strong in Devon and Cornwall. As soon as I was old enough I favoured Liberalism, much to the disgust of my relatives. Most Nonconformists were Liberals and those I knew were also teetotallers. North Devon had a Liberal Member for several years, then turned Conservative. Later, in a three cornered fight, Labour polled more than the Liberals. So public opinion changes.

Another popular hobby in my younger days was bell ringing. Often we visited surrounding parishes for organised competitions. In this way we made a number of friends, so that if we happened to be in their locality we were always sure of a welcome. The same applied to parties of singers. There were some comedians whose service was in great demand for village concerts, and their talent was quite up to and even better than some who perform on the BBC. Simpler things gave us pleasure and the fact that we knew all the performers added to our enjoyment. Skittles were played on a nice level piece of grass, but always with large wooden balls. Quoits was another popular game at any gathering. On such occasions as a Jubilee or Coronation, we had very special festivities. People subscribed to the prize fund and many competitions were run for folk of all ages. A favourite one was a race across the field to the tidal river, which had to be crossed at low water, through the mud, then up the road and back again. What energy this required! Yet there were plenty of competitors. The chief event was a most sumptuous tea on tables set up in the field and presided over by the farmers' wives, always with large dishes of Devonshire cream. The memory of those days has remained with us throughout our lives, but although the population has increased, villages do not seem to organise on that scale today.

In the generation earlier, they had what they called club walks. The village ran a sick club to which members subscribed a few coppers each month, and when ill they drew certain benefits. On their annual club day they attended church and the wrestlers among them wore the spoons they had won in the bands of their bowler hats. Wrestling had almost vanished in my day, but old John was still drawing a little from the club, of which he was one of the few surviving members. In summer farmers organised parties to go picking mussels at Lower Yelland. At low tide you would gather basketfuls together with cockles, winkles and limpets. The first ones were brought to the womenfolk, who cooked them for the great feed when all had finished filling their baskets. Then to skittles and games, with the beer barrel close at hand.

In my grandfather's time, apprentices' indentures stated that they must not have salmon more than a certain number of times per week. Salmon were caught in special weirs of which the remains were still to be seen in the river and in those days this fish was so plentiful that it was the chief food, hence the need to protect apprentices from an all fish diet. River pollution has altered all this until now it is dangerous to eat mussels and they are supposed to be gathered only for bait. A few salmon boats still fish the rivers Taw and Torridge, but catches are small, as is the rod and line catch. Our streams contained trout, which could be seen in the water under Fremington bridge. Boys tickled trout in this stream further up in the woods. One summer evening I disturbed them when they were climbing the weir of the millpond, and what a splash they made on their downward journey! We also groped for flook in the tidal steam, walking upstream at low water with hands outstretched ready to hold the fish. Besides this, in the ponds left in the sand banks in the river would be found very big flat fish, which we set about catching by treading on them. With all these sports available, country lads found plenty to amuse themselves.

My grandfather, Edwin Beer Fishley, was about seventy years old when I joined him, but of course I had known him for as long as I could remember. Somehow I never looked on him as an old man, as he was vigorous and beaming and could do his day's work with the rest. He was a small man with a well trimmed white beard, a slightly hooked nose, a fine complexion and bright blue eyes which had a twinkle, especially when he was in the company of his special friends. He was not a talker generally, but was always enthusiastic on subjects which interested him. They were many and varied and somewhat above the ordinary. He loved nature, his garden, his fields, his flowers, and animals and children amused him greatly. He was generous, and although not wealthy, in fact often short of ready cash, he did his best for all his men.

One thing he would not tolerate was bad language. We had an old sailor as horseman who swore habitually and I have heard grandfather threaten him with the sack. Bill would reply: 'I'm sorry, Maister, but I don't know when I'm saying it.' He really tried to avoid bad words till something excited him, then off he went into his own vocabulary quite unconsciously. All the men would do anything possible to please 'Maister'. He was happy with good books, but not novels. His office was piled with magazines and all the issues of pottery journals besides his most valued books.

Grandfather's daily routine was most regular and you could be fairly sure where to find him at any time of day. He always drank coffee for breakfast (whilst we all took tea), had a cooked lunch at eleven, a nap at dinner time, ate a good tea, then in summer, after sitting down for a while he would wander off, sometimes with his gun but always with his little dog Turk. In winter, he read, or took down his fiddle and we had some of the very old tunes, which he could play by heart. To finish his day he had a tot of whisky, then off to bed to be up early in the morning and ready for work after breakfast. These were his regular habits except on Fridays, when he went to his stall in Barnstaple market.

This was his recreation day, when he had a glass of beer with his friends and when he would meet visitors who were interested in pots.

He could walk smartly and up rightly up to the last, although he sometimes remarked that he had 'screws'. It was said that he only attended church for weddings and funerals. Then he wore a frock coat and top hat and was really smart. He certainly was none the worse for not attending church. I am sure he had his own ideals, and those of high standard. He never grumbled without good cause; and, having stated his opinion, all was forgotten.

|  | | Frock coats above and top hat right.. |  |

In spring, all the men would go to the garden to do the tilling and all would have beer on those days- which they much appreciated. I suppose unions would oppose such things now, yet those fellows enjoyed every minute of it and were proud of the crops we produced. When I was able to throw any and every kind of pot, grandfather spent most of his time on his fine ware and on glazing experiments in his special cubby-hole in the old cottage. The doors and all available space were covered with records of his trials such as: 'painted plate with treacle and CuO and splashed oxide of iron', and so on. How he must have enjoyed his few years of freedom, after having to keep in harness for so long.

My fiancée was in the Post Office at Fremington and, as we were able to share part of her parents' house, we got married when I was twenty one and she still managed the office for her father. I then had a guinea per week wages. Grandfather, considering my future, asked me if I could raise enough money to buy the pottery. My father in law was prepared to let me have some money, also an old uncle, so we talked of paying grandfather a lump sum and three pounds a week for life. Remember he was nearly eighty and wished to work as and when he felt inclined, which then seemed to be every day. Before we came to a definite agreement, he was taken ill and passed on.

One cold autumn day he stood watching the thresher at the farm and caught cold. He made some Bideford jugs, then walked across the yard with a fit of coughing, went in and said to my mother: 'Very much of that and I shall soon be gone.' Inside a week he was, and without much suffering; in fact, he was cheerful to the end. I finished off those jugs and have always regretted that I did not keep one for myself. I shall never know whether or not he had discussed his intentions with his family, but his will stated that all his assets were to be divided between his four sons and daughters. It was a tremendous blow to me to lose him, possibly more so than to anyone else. The fact that I was not mentioned in the will did not seem to worry me one bit. I had faith in my ability to get on somewhere. I knew his intentions, and this set back acted as a spur. He certainly left me with the ability to earn a living, the memory of a great craftsman and a grandfather to be proud of. After my grandfather's death I carried on the pottery, doing all the correspondence and booking, in fact having absolute control. My two uncles were the executors. One lived at Torrington, the other near Exeter, and they came together only occasionally. The elder had been a potter, but he had left the trade long ago and took no part in the management. Maybe his brother had told him not to interfere with me. Unfortunately the elder uncle did not favour my being in charge and seemed jealous of the progress I had made with grandfather, which made matters a bit uncomfortable for me. It was a case of trying to please them both, yet doing as I thought best for the prosperity of the pottery. I was promised a fair deal if I carried on until the affairs were settled. After about a year, however, things got so bad through interference that I determined to bring matters to a head by giving in my notice to leave. I had no idea what was in their minds regarding the disposal of the pottery but had been given to understand that I should have every consideration. Trade had been extremely good and there was nothing to complain of financially.

The handing in of my notice set things in motion. On a Sunday morning two men appeared at the pottery. They were so keen to see the place that I asked them if they were interested in buying it. One said he would not consider such an old place, but that he was from Staffordshire and was interested in our red ware glaze. He offered to give me a recipe of a matt glaze if I would give him one of ours in exchange. As three or us knew how to mix this, I saw no reason to withhold it; besides, I was not so wise then and far more trusting.

Fremington estate and farms were then managed by a gentleman on behalf of his aunt and he approached me with a view to joining him in the purchase of the pottery so that we could make bricks, tiles, drainpipes and so on for the estate. We agreed that he should negotiate the purchase, and later he attended a meeting in Barnstaple which was arranged for the sale of the pottery.

It then turned out that my uncle had already agreed to sell it to the man I had seen on that Sunday morning. He afterwards proudly showed me his trial of glaze made from my recipe. He had been given to understand that I would be bound to work for him. No other pottery, he seemed to think, would employ me because my association with Fremington pottery and my Fishley connections would make my intentions suspect.

Just before lunch that day, the person from Staffordshire came to the Post Office to see me and told me he had purchased the pottery. After I had reminded him of the remark he made on the Sunday, he offered me a job at twenty five shillings a week. When I told him I would not consider anything less than thirty shillings he disclosed that he knew that grandfather and my uncles had paid me only a guinea a week. He evidently had been well informed about my position and had decided to adopt a firm attitude, thinking I must come to his terms. He did not know what type of fellow he was dealing with. When I set my mind on any particular course, it takes a great deal to put me out of my stride and I have always endeavoured to be a sticker. He told me he would be at the farm adjoining the pottery until the afternoon and that I must think things over and give him an answer before he returned to Staffordshire. I had absolute faith that the situation was in my control, and to his confident 'Well?' I replied: 'As I said this morning.' 'Well,' he said, 'this is where we part.' He held out his hand to say good-bye, then watched me out of sight, all the time expecting me to alter my decision. But I was adamant and would rather have taken on any job than give in. Such is the stuff of which I am made.

I had not had time to consider anything very deeply, but felt an urge to go to Barnstaple, having a vague idea that something must happen. This sounds like a fairy tale, but is absolutely true in every detail. The first man I met was Mr Adam Oliver, manager of the Barnstaple Cabinet Company. He was a great friend of my family and had formerly lived at Fremington, where we had worked together on church concerts. My welfare interested him in a fatherly way. He knew that I should normally be home at work, and he asked 'What are you doing in town?' When I told him that my uncles had sold the pottery to a stranger, his reply was not very complimentary to them. He had been well acquainted with my grandfather, my uncles and everything connected with the place for many years and had seen me grow up in it.

He asked what I had in mind. I told him that I had seen in our local newspaper that someone was hoping to start a pottery in Braunton, and I was seeking information in hopes that there may be a job there. Without further comment he took me a short distance to a solicitor's office and left me standing outside. When he returned he said: 'He is in and will see you. You are the very chap and I wish you good luck.' I entered the office hoping that I might be considered as a thrower, or to do some other part of the work. When I was greeted with 'Well, Mr Holland, I hear you have come to apply for the position of manager of our pottery,' I hid my surprise and replied in the affirmative. He asked all about my experience with my grandfather. Could I mix the glazes and colours that he made? What sort of trade had we been doing since his death? and many other relevant questions. I gave a truthful account of everything. My reason for leaving was satisfactory and there seemed to be no other obstacles. He then informed me that a manager had already been tentatively engaged. He was a brick maker. Could I make bricks? I said 'Yes, a potter can make bricks, but I doubt if a brick maker can make pots.' He then wanted to know what salary I required. It was all such a surprise to me that I had to proceed with great tact, but the words were given to me. I said: 'As you have engaged a manager, you have no doubt agreed on a figure; so if you would not mind telling me what that figure is, I will tell you whether or not I could consider it.' When he mentioned two pounds a week, my heart gave a jump. I replied, as calmly, as I could that I would accept that figure on condition that if and when I made the pottery pay my salary would be increased. 'Most fair, Mr Holland,' he replied.

It chanced that this same gentleman had tried to negotiate with my grandfather for the purchase of his pottery some years before, with a view to turning it into a syndicate. But grandfather was a man of great independence and, although he might have made a good deal of money, he preferred to be free to do just what he wished to the end of his days. I had once tested some clay for a gentleman who had approached grandfather in the market. It was this same clay that the new pottery was to develop, but I did not know it at the time.

Imagine my joy and excitement on telling my wife and my mother the good news and in thanking my great friend Adam Oliver. The appointment had come like a bolt from the blue, an event which I never cease to wonder about and which has been an inspiration to me ever since.

Early next day a telegram from the Staffordshire man arrived saying: 'Your offer accepted.' My reply was very brief: 'Too late.' This must have given him a great shock, as developments proved. He knew nothing of Fremington methods, which were entirely different from those of Staffordshire. All potters have their individual ways of working to say nothing of getting to understand their particular kilns. Within a few months, when I was in the throes of getting Braunton pottery going, I was offered Fremington pottery at any figure I cared to state! It would have been much easier for me to have gone back and carried on the place I was so well acquainted with instead of struggling to get my new place in order; but I have always found honesty and playing the game is the only right and true way to live one's life.

These events happened so quickly that the great uprooting gave all of us a surprise. I left the pottery on a Saturday and it was sold early the next week. I started at Braunton on the following Monday, so I have only been out of work for one week during my whole lifetime. At Braunton, I was shown an orchard. This was the site the pottery would occupy. I was to supervise the building and to state what I required. |

Strong's Industries of North Devon, 1889

David & Charles reprint 1971.

XII THE FREMINGTON POTTERY

"Time's wheel runs back or stops: Potter and clay endure." And so, in this series of articles, we have again recurred to the industry which boasts the profoundest antiquity. At Fremington, in the quiet of modesty, may be found another son of Num, the directing spirit of the universe and oldest of created beings, who first exercised the potter's art, moulding the human race on the wheel; he that modelled man out of dark Nilotic clay. To descend from mythology to more mundane things-- Mr Edwin B. Fishley, of Combrew, Fremington, is the representative of the three generations of potters whom Mr. Llewellyn Jewitt mentions as resident at Fremington. We may dispose of any question as to the qualification of the Fremington Pottery to rank among the industries of North Devon by pointing to the fact that the present Mr. Fishley was the first to solve the problem as to whether colour could be applied to local clay. He was a pioneer in local decorative ware. Mr Fishley won the first bronze medal for ware at the Plymouth Art and Industrial Exhibition, 1881-- a success which he capped by carrying off the silver trophy at the Newton Abbot Art Exhibition in 1882. He also received a certificate at Exeter.

Fremington can boast the most picturesque pottery, for the premises upon which Mr Fishley carries on his interesting occupation abounds in quaint corners and curious "bits" which the artist itches to transfer to his sketch-book, so original are they. The ware shares in the unique character of the scene, and it is nothing short of a delightful hour which is passed in inspecting the holes and corners of the pottery and picking up the odds and ends of the potter's art. Situate on rising ground above the Pill and its pretty surroundings and with all the outward appearances of a country homestead-- an illusion which is promoted by the long range of low outhouses, call of chanticleer and cackle of hens, strutting and pecking about the open yard-- the pottery is the centre of an old-world picture of the life of the worker at the wheel remote from towns. It was established by George Fishley, grandfather of the present proprietor, towards the close of the eighteenth century, but the site of the original pottery was at Muddlebridge, on the Pill, some fifty yards river-wards. At that time, however, there existed a pottery at Combrew, and it was with one of the employees of its owners that Mr Fishley commenced the manufacture of that Fremington ware the soundness of which-- at least, in Cornwall,-- is a household word. Muddlebridge was probably the site of a pottery in the days of long ago. Evidence of the pre-existence of potteries in the locality is not wanting. Not many years since, in the course of some excavations for building purposes tiles bearing a fleur-de-lys design and the initials "IW" were unearthed; they were worn, but were certainly locally manufactured and of Fremington clay. Mr George Fishley lived to a grand old age, and, when, "in the Nineties," passed the hours that hung heavily upon his hands in forming curious articles with plastic ware. Jealously preserved to this day are two very quaint watch-pockets which he modelled and decorated with heads and odd scraps of ornament. A pitcher thrown by him, and bearing, in all its richness, the golden yellow glaze which is a characteristic of Fremington pottery, is shewn with the name of the person for whom it was intended inscribed upon it, together with one of the well wishing quatrains, the appearance of which upon the ewers, jugs and loving-cups is a survival of an ancient custom. It reads:

Long may you live,

Happy may you be;

Blest with content,

And from misfortune free.

There are several other and happier instances in which the potter, like Silas Wegg, had "dropped into poetry", which will occur to us in the course of our description.

Mr. Edmund Fishley succeeded his father in the business. His accidental death led to the concern passing into the hands of the present manager, Mr Edwin B. Fishley, who has carried on the pottery for the last thirty years. Public attention was first called to the Fremington ware when Mr Fishley exhibited some good specimens of it at the Barnstaple Show of the Bath and West of England Agricultural Association. Here it attracted the interest of Sir John Walrond, Sir Thos. Acland and "Squire Divett", of the firm of Buller and Divett, Bovey Tracey. Sir John Walrond was so favourably impressed with the qualities of the ware and manifested such an insight into the possibilities of its development in the direction of decorative work, that he undertook to send Mr. Fishley some designs. This he did, and among the specimens of decorated ware which Mr Fishley exhibits is a fine cope of a Greek vase upon which is depicted the wedding of Bellerophon to the daughter of the Lysian monarch-- decoration in white upon a red ground. The vase itself is not a copy of the Greek in shape, although an excellent example of the amphora; and beside the clever reproduction of the Attic decoration, Mr Fishley has manifested no little taste and kill in the original supplementary ornamentation of the vase, consisting of a collar in keeping with the whole design. There were a pair of these vases, designed from the sketches supplied by Sir John Walrond, the other, which has become the possession of some luck virtuoso, illustrating the classical story of Bellerophon destroying the monster called the Chimaera, the glorious god being mounted on the winged horse, Pegasus, received from Minerva. Thus encouraged, Mr Fishley, who is a self taught designer in the best sense of the term, turned his attention to Sgraffiato work; with what success the bronze medal of 1881 and the silver award of 1882-- each adjudged by eminently qualified judges-- records. A loving cup, with a colour and an inscription redolent of "the rich Rhine wine," survives, with many another richly-glazed pot, as evidences of the taste and innate knowledge of the potter's art possessed by Mr Fishley. One of the vases with figure and floriated design, the former of which was supplied by Mr Ireland, an old master of the Barnstaple School of Art, marks another early stage in the history of decorative ware production at the Fremington Pottery.

From the first, as it appeared to us, the manufactures of Mr Fishley excelled in one particular; their form was irreproachable. In the variety of shapes that met our eyes, as we ranged over the "throwing" house, the kiln and the store rooms, the symmetrical beauty of all the vessels was everywhere conspicuous, being as noticeable in the "penny joogs" as in the few specimens of decorative ware on view. Cylindrical vases and the common earthenware told the same tale. After all, there is much in the "throwing" of the vase. The pot is the thing-- to adapt an historic phrase. Mr Fishley himself throw the superior Fremington ware. "If you want a thing done well, do it yourself," says the axiom of our grandfathers; and this potter acts up to the spirit and the letter of the proverb. The truth he knows:

The potter's clay is in thy hands,-- to mould it or to mar it at thy will,

Or idly to leave it in the sun, an uncouth lump to harden.

Mr Fishley has some clever imitations of Japanese and Egyptian designs, and in numerous ways has shewn his penchant for the decorative side of his art. He has the material and the practical knowledge. There is, in a word, the nucleus of a most profitable art industry at Fremington, and the previous achievements of Mr Fishley in this direction warrant us in expressing a confident opinion that were the alchemy of capital, skilled labour, and enterprise applied to Fremington pottery, it would bring into existence a decorative ware which would successfully compete with much that is in the market today.

But if the artistic department is as yet undeveloped so much cannot be said, of the commoner sorts of Fremington pottery. Mr Fishley's pots, pans, pipes and pitchers by the superiority of their manufacture. Their shapes are good, their glazes rich and hard. Here and there is a bit of moulding-- a bend round a sea-kale pot or bread pan, and an ornamental trade make of their own on the ovens-- bespeak a liking for ornament on the part of the potter.

Here at Fremington we are again familiarised with "localisms" -- descriptions of pottery which are a strange language to the uninitiated. Cornwall is a great market for the Fremington ware, partially, from the facility of transport by water to which the Fishleys have had recourse in distributing their manufactures. Many a good ship load of the big ovens in which the Cornishman bakes his bread, and pitchers and pans have left Fremington for the Cornish ports of Padstow, and Hayle, "Bude and Bos." The size of these ovens are calculated by "pecks". But a "10 peck oven," in which "the giant Cormoran" slain by Jack, the valiant Cornishman," might have "made his bread," is of far greater capacity than the "measure" indicates. These ovens are heated by furze burnt on the interior; the ashes are removed when the oven is at white heat, and the bread put in. Another export peculiar to Cornwall is the fish "stain"-- a pot in which pilchards are pickled. The different sizes are styled "great crocks", "buzzards" and "gallons". Fremington pottery is sold by the "tale"-- a way of counting which takes us back again to the banks of sacred Nile. Rustic flower-pots of appropriate design and well hardened ware, and orchid baskets, the like of those which, at Castle Hill, contain, in such luxurious profusion, the flower beloved of Mr Joseph Chamberlain, the "companion of gentlemen," are pretty examples of the manufactures.

Harvest jugs are a specialite of the Fremington pottery and one of its quaintest productions. The rhyming injunctions to the harvester who indulges in "potations pottle deep" have tickled the fancies of many a connoisseur in pottery, and it is with little surprise that we learn of the sedate Lord Chief Justice having been inveigled into the purchase of a "tale" or two of these curious jugs by their originality. Who could withstand such an appeal as this, for instance?

Fill us full or liquor sweet,

For that is good where friends do meet:

When friends do meet and liquor plenty,

Fill me again when I be empty.

Lord Coleridge, at any rate, could not. Then again, there is this excellent toast:

Success to the farmer,

The plough and the flail;

May the landlord ever flourish,

And the tenant never fail.

And the jovial huntsman, the shepherd, and the farmer will surely clink glasses with the men of the scythe, and the sickle in pledging this "health":

Good luck to the hoof and the horn,

Good luck to the flock and the fleece;

Good luck to growers of corn:

May we always have plenty and peace.

These harvest jugs have a slip of pipe-clay on the red and are decorated, here with a leaf, there with a scroll. But perhaps their manufacture is told to a more popular tune in another inscription:

From mother earth I took my birth,

Then formed a jug by man;

And now stands here filled with good cheer,

Drink of me while you can.

The clay is obtained by Mr Fishley from pits about half-a-mile from Combrew. By a judicious mixture, which is evidently a prized secret, a terra cotta of rich colour, a fine strong ware, is produced at Fremington. Mr Fishley has also solved the problem of glazing the terra cotta bottle throughout the interior-- a difficulty which potters generally get over by simply glazing the lip of the bottle, leaving the superficial observer to infer the glaze covers the whole of the inside of the vessel.

Mr Fishley has dabbled in tiles, and succeeded in firing a series which would make admirable flooring, the usual indications being strongly in favour of their wearing well. He has a mediaeval design stamped upon them, the machine for pressing the pattern being of his own manufacture. This reminds us of another original mechanical aid with which we have not previously been made acquainted in the potteries already noticed. It is in the shape of a perpendicular pipe making machine, which has certain obvious advantages. Drain pipes, of course, are among the most extensive manufactures of Mr Fishley.

Among the quaint and unique vessels, whose shapes, peculiar and pretty, at once attract attention, are the "porringers" from whence our forefathers ate their nourishing "spoon-meat". Alas! in the desuetude that has followed those "good old days" the porringer has suffered, and to-day we find it playing the ignominious part of paint-pot! From porringer to pain pot-- what a falling off was there.

Beloved of the colourist is the "yellow-drum" pitcher with its rich golden glaze. In this instance, as in all others, the Fremington Pottery impresses the observer by the excellence of the throwing, the goodness of the glaze., and the hard, resisting qualities of this enamel. Through one ware room after another pots and pans and pitchers are stored for the Spring market, and anyone following in our footsteps a month hence will probably find these cleverly piled rows of vessels "conspicuous by their absence".

Although, as has been observed, the artistic side of the industry at Fremington has, so to speak, been allowed to remain in a dormant state, the ware is in demand for decorative purposes. If not the rose, Mr Fishley lives very near it. He is now manufacturing great numbers of dainty little jugs and large symmetrical pots which will be painted after they have left the pottery. In the interests of industrial North Devon we may desire the time when art and labour shall join hands "on the premises" and another artistic manufacture be added to those which have been received in these articles. |

|

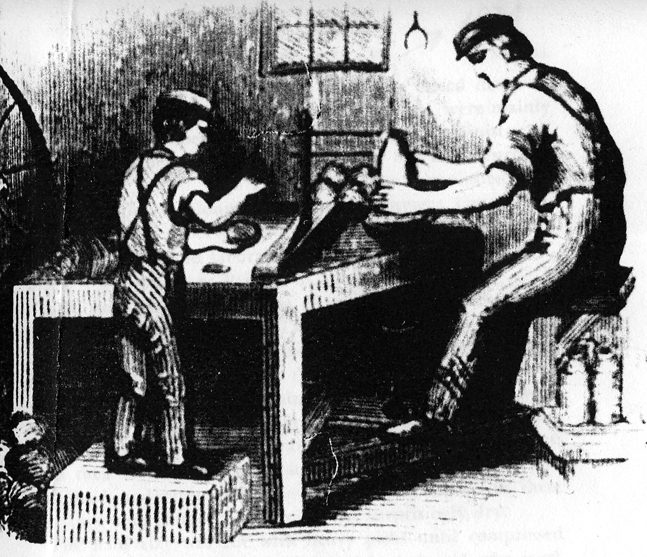

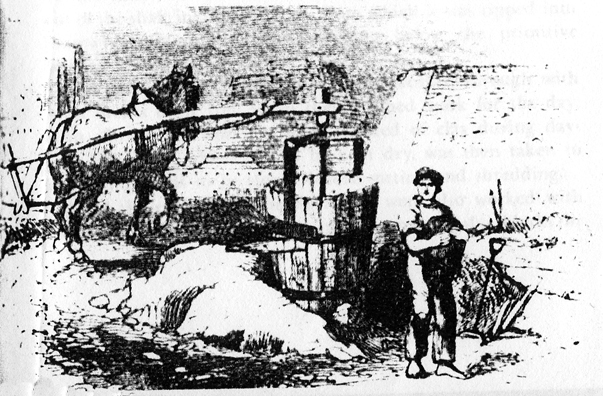

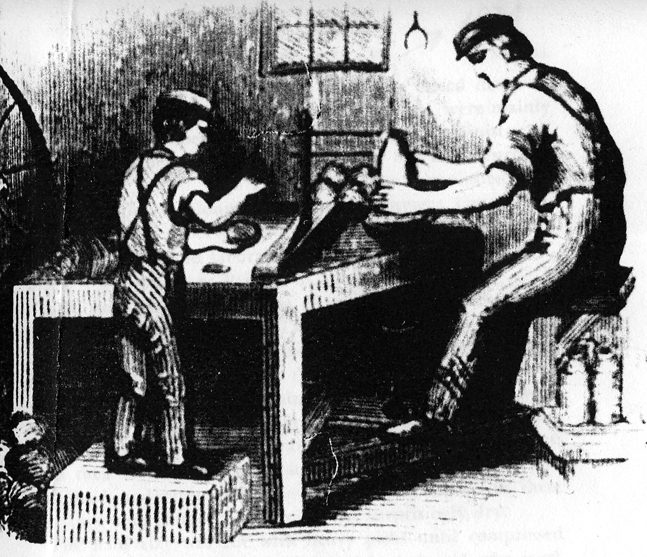

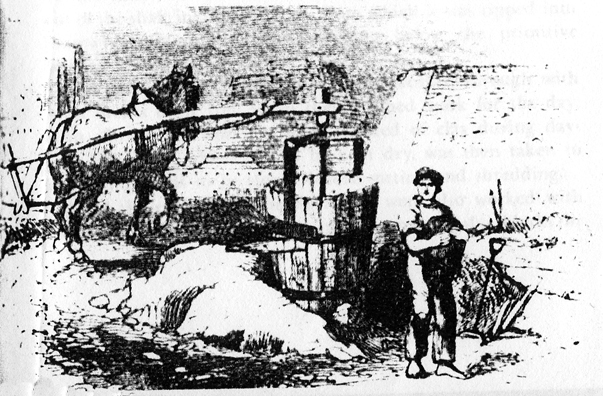

| Plate 17 (above) Throwing pots, as described in section XII on Fremington Pottery. Note the labourer turning the large wheel to provide the power; an illustration of 1851; 18 (below) a horse powered pug mill. Crude mills of this type were used in most local potteries and brick works; an illustration of 1851. |

|

NOTES ON THE ARTICLES

ARTICLE XI Chappele's Yard Torrington

Strong's argument for including Chaeppele's Skiver Dressing Yard at Torrington is a little difficult to follow, but there is no doubt that the tanning of leather was once an importance industry in the area. Most north Devon towns had a least one tannery, but Torrington became quite a centre for the industry and at one time had five tanneries in addition to the Skivers yard. The building of three of them are still standing, and part of one has been converted for use as a cinema.

Most of the buildings which housed Chappele's Tannery have now been demolished though one has been kept in good repair and is used by a builders' merchants as a store.

The water-driven tucking mill at Weare Gifford, where all the fulling of the skins was carried out prior to the installation of steam engines at the Torrington yard, has had an interesting history of it sown. Until 1850 when the tannery took it over, the mill housed Turton's Blanket Factory. Cloth for the blankets was probably woven in the villages and farms surrounding, but the mechanical process of carding the wool, and fulling the cloth to shrink and felt it, were carried out at the mill.

The carding machine used in the mill survived until about 1950 in the workshop of a Torrington cabinet maker who used it for reflocking old mattresses. Unfortunately it was broken up when no longer needed, though it was photographed before being destroyed.

When the fulling mill was no longer needed by the tannery all the machinery was dismantled and the building converted for use as a blacksmith's forge.

|

|

ARTICLE XII Fremington Pottery

Fremington Pottery closed down between 1912 and 1914; the site is now occupied by Wrights, a small electrical engineering firm. Only the house and part of one of the store rooms of the old pottery still remain. The main products of the Fishley pottery-- pitchers, pilchard stains, meat pickling pans, ovens, yeast and bread jars-- where vessels used in the storing or preservation of foodstuffs and it is interesting to note that the electrical firm now on the site specialises in the manufacture of deep freeze refrigerators.

On the death of Edwin Beer Fishley in 1911, his grandson William Fishley-Holland, carried on the firm for his two uncles. In 1912 he left and started his own pottery at Braunton. The Fremington Pottery was taken over by C. H. Brannam of Barnstaple but it was soon closed down and was demolished shortly afterwards.

In his book Fifty Years a Potter published by Pottery Quarterly in 1958, Mr Fishley-Holland has described his early life in Fremington Pottery. As a journeyman potter he was paid 21 shillings a week in 1912. Work started at 6am; breakfast was from 8 to 8.30. At 11am a cooked meal was provided and work start again at 11.30. There was a tea of coffee break at about 1pm then the afternoon's work continued until 6pm in summer or until it was too dark to see in winter. There was no lunch break on Saturdays but work finished at 4.30. On Fridays, the firm ran a stall in Barnstaple Market.

The potters had to work hard as the retail price of their goods was low even for those days. Ovens costs about 1 1/2d per peck; if an oven's interior would hold eight pecks, its cost was 1s. Pitchers costs between 1 1/2d for a 1 1/2 pint size to 7d for a 2 gallon one.

Fishley quay near the site of the old pottery is still visible but very outgrown and dilapidated. The quay was used by the small sailing coasters when loading cargoes of ovens and pottery for the ports of north Cornwall and Somerset.

|

|

ARTICLE XIV MARLAND TERRA-COTTA BRICK & STONEWARE PIPE WORKS

Clay beds in the Peters Marland basin have been worked for well over 300 years, the first records of operation dating from 1680. The clay continues to be worked for the North Devon Clay Company, but the brick and tile works closed down in 1942. The buildings which, apart from the kilns, were mainly constructed of timber, were then used by the Ministry of Supply until August 1944 when fire broke out and destroyed most of the works. The kilns were later demolished and levelled to provide foundations for the present large sheds where the clay is processed, graded and stored. The company's workshops, offices and laboratory are also situated in this area which is still known as Brickyards.

Unfortunately Strong has not given us a description of the clay workings in his account. This is not surprising, as a tour through the workings usually means wading through a sea of mud. Until the spring of 1969 the clay was extracted by both opencast and underground mining. The underground work was done in shallow timber lined shafts which started with a short steep slope of about 50ft at an angle of about 45 degrees. This then levelled out to a slope of about one in five and continued underground for up to 700 ft. Conditions in these working were cramped and noisy, but surprisingly dry.

The hard clay was cut with heavy picks until compressed air shovels were introduced. Even with their aid, the work was extremely trying as the shovels, weighing about 50lb had to be held up to the roof of the shaft then brought downwards in an arc across the clay face and the lifted back to the roof for the next cut. A surface winding engine hauled the clay out of the shaft in a small truck, from which it was tipped into narrow gauge railway trucks waiting below the primitive wooden head gear.

The miners started work at 6am and worked through with short breaks until 1pm when they finished work for the day. This allowed the workings to be cleared of clay during daylight. The clay, which had to be kept dry, was then taken to the drying sheds to be stored before sorting and shredding.

Until the early 1930s, the open pits were also worked with hand tools. The clays was first cut into rectangular blocks by. . . |

North Devon Pottery: The 17th Century

by Alison Grant, 1983.

There probably were village potters working in North Devon in the Middle Ages, for only the simplest of tools and a home made kiln was needed, together with a local supply of clay. At Monkleigh near Bideford, a clay rent was paid in 1369-70, and Clampit Wood, which probably got its name from cloam (clay) pits beside the River Torridge there would have made a good pottery site.

At Martinhoe, on the cliffs overlooking the Bristol Channel, field names including Crock Meadow and Crock Pitts, suggest another site and Potter's Hill and Mortehoe near Woolacombe perhaps another. By the seventeenth century, however, such potteries had vanished for town potteries could market better wares over a wider area.

The only village potteries to survive were a few accessible by sea of river. Instow near the confluence of the Taw sand Torridge rivers, had a quay built in the 1620s and was probably the site of a seventeenth-century pottery, for there is similarity between sherds found there, and others discovered in excavations at Carrickfergus in Ulster, with which Instow ships traded then.

The first documentary reference to the Instow pottery, however, is not to be found until 1790, when the potter, William Fishley, took an apprentice. His ancestors, Fishleys who lived at Instow in the seventeenth century, could also have been potters, or perhaps the pottery there was started by the Rice family, with whom the Fishleys were linked by marriage. Joseph Rice, later to be a potter in Barnstaple was baptised in Instow in 1751, five years after William Fishley.

A branch of the Fishley family had moved to Fremington by 1800. This large parish, only three miles from Barnstaple, was an obvious site for potteries, for the clay pits were there at Combrew, where these is said to have been a pottery before the Fishleys' time.

William Fishley Holland, the last Fremington potter, wrote 'there were others around Fremington and one at Clampits of which I remember seeing the remains. At Clampits about a mile to the north of Combrew, the clay was of a lower grade, and in the nineteenth century, bricks, ridge tiles and field drains were made of it. Although there is no evidence of an earlier pottery, the pits could have been worked before. The yard, with the kiln in the centre, lay right beside the pits, and such sites may also have existed at Combrew, with a potter's house close at hand. A "messuage or tenement called Hammett's together with the Clay Pitts therewith, lying in or near the said village of Combrew in Fremington' could have been such a place. Pentecost Hammett must have been an associate of William Oliver, who stood as surety for him in the sum of £_10 in 1668. Hammett is therefore quite likely to have supplied the Barnstaple potter with clay and could also have been a potter himself. John Hammett, who married Judith Rice at Fremington in 1689, was probably the 'John son of Pentecost Hammett' baptised there in 1658, so there were connections with Rices also. It is likely that the tenants of the clay pits included other potters, but the only seventeenth century Fremington potter who can be certainly identified was apparently not working at Combrew. Joseph Westlade of Fremington, who is 1669 was selling his pottery in Barnstaple with William Oliver and others, was baptised at Fremington in 1639, the son of John Westlade. In that year, John Westlade, probably the same man was presented at the manor court for failing to keep the 'cursus' at the lower end of the gravel pits in good repair. There are no gravel pits in Fremington now, but the word cursus seems best translated by causeway or causey, a word commonly used in the seventeenth century to describe a paved way through water or across a tidal marsh. The road leading from the village to Barnstaple crosses the tidal Fremington Pill at Muddlebridge, where part of an old stone causeway was uncovered during recent road alterations. Near Muddlebridge House gravel lies only a few inches under the ground and the pits could have been in this vicinity. As the causey was John Westlade's responsibility he must have lived near it. At the British Museum is a seventeenth century relief tile 'from a pottery at Muddlebridge' and the remains of an old pottery can be seen behind Muddlebridge House. This dates from the late eighteenth century, but was built on the site of an earlier one. No systematic excavation has taken place at Muddlebridge but large numbers of waster sherds are found whenever the ground is dug. Wares from this pottery must have been sold locally and about one hundred years ago 'in the course of some excavations for building purposes, tiles bearing a fleur-de-lys design and the initials "IW" were unearthed in Fremington. These were probably identical with the floor tiles still to be seen in Fremington Church. These initials are found nowhere else, so the tiles are likely to have been the work of either Joseph Westlade the Fremington potter, or his father John, who is likely to have worked at Muddlebridge before him, or perhaps some other member of his family. Fremington potters seem to have enjoyed equal status to those at Barnstaple with whom they associated. In the village they probably cultivated a smallholding, like their nineteenth century successors, who were self supporting. At that time the Fishleys kept hens, pigs and cows, grew corn and potatoes, had a 'fine garden' and made wine from the fruit of their own vine. George Fishley, who bought the holding in 1801, was described as potter on one deed and yeoman on another. The words husbandman and yeoman probably conceal the identity of seventeenth century potters in the records of Fremington and other villages.

"Clay, I tell you," wrote the vicar of Fremington in 1775, in answer to an enquiry about the composition of the soil of his parish. He had already described the "Great Quantity of Clay which supplied Barnstaple, Wales, Cornwall, [and] Ireland, for Potters' Use". Pottery made of Fremington clay must have been made outside North Devon by that time, and in the seventeenth century potters' clay was already being shipped to Wales and Cornwall. The only shipments to Wales recorded in the surviving Barnstaple port books were ten tons in 1682, on in 1697 and twelve in 1698, all to Milford. Small amounts of lead ore were also sent there, the merchant for half a ton shipped in 1676 being Susan Moore, who had perhaps ordered it for a potter in Milford, for there is no further reference to her from the North Devon side. At Haverfordwest, which was part of the port of Milford, sherds thought to be wasters of North Devon pottery have been found in excavations. It has been suggested that they arrived as part of ships' ballast, but it is possible that they came from a local kiln using Fremington clay. It is even possible that a North Devon potter settled there and sent home for the clay and lead ore, for this happened in Cornwall. In 1675, a potter called John Burnard was working in Forrabury, the parish of which Boscastle was a part, and three years later, John Bernard (sic) was recorded as merchant for twelve tons of potters' clay sent to Boscastle from North Devon. For customs purposes, Boscastle was part of the port of Padstow, so the same potter probably received clay listed for Padstow also. No pottery site has been found, but John Burnard probably worked as close to a harbour or landing place as possible, to avoid the cost of transporting heavy materials inland. The first recorded shipment of potters' clay to Padstow was in 1661, two years after John Barnard (six) had married Elizabeth Chope at Bideford, in the presence of Gabriel Beale and John Brown. This was obviously a potter's wedding for the bride's brother was Neighton Chope who was probably a potter working in Mill Street, while her father, Philip, if not a potter himself was almost certainly related to other Chopes who were. Gabriel Beale too, if not a relation was probably there as an employer or master, perhaps of the bridegroom, and the other witness was possibly a potter also, for there was a later Bideford potter called Brown. Why John Burnard moved to Boscastle is impossible to say but he seems to have succeeded if the increase in the amounts of clay and lead ore shipped to Padstow and/or Boscastle is any criterion (Figure 14). Shipments ended abruptly in 1679, so John Burnard may have died or given up business at that time. The Boscastle pottery, over forty miles from Bideford, can nevertheless be considered as an extension of North Devon's, for Burnard's wares were probably in the usual Bideford range. Coarse-wares of Fremington clay tempered with Cornish grit, which contains specks of black mice not present in Torridge gravel, had been found in excavations near Boscastle and could have been made by John Burnard or perhaps another potter who had moved out in search of a new market. One and a half tons of potters' clay sent to St Ives in 1684 do not suggest a pottery of the Boscastle scale, but perhaps represent a special order by a Cornish potter. No other records of the transport of clay by sea in the seventeenth century are to be found, but it could have been taken by packhorse or cart to villages...

|