Much of Tyndale's work eventually found its way into the King James Version (or Authorised Version) of the Bible, published in 1611, which, though nominally the work of 54 independent scholars, is based primarily on Tyndale's translations.

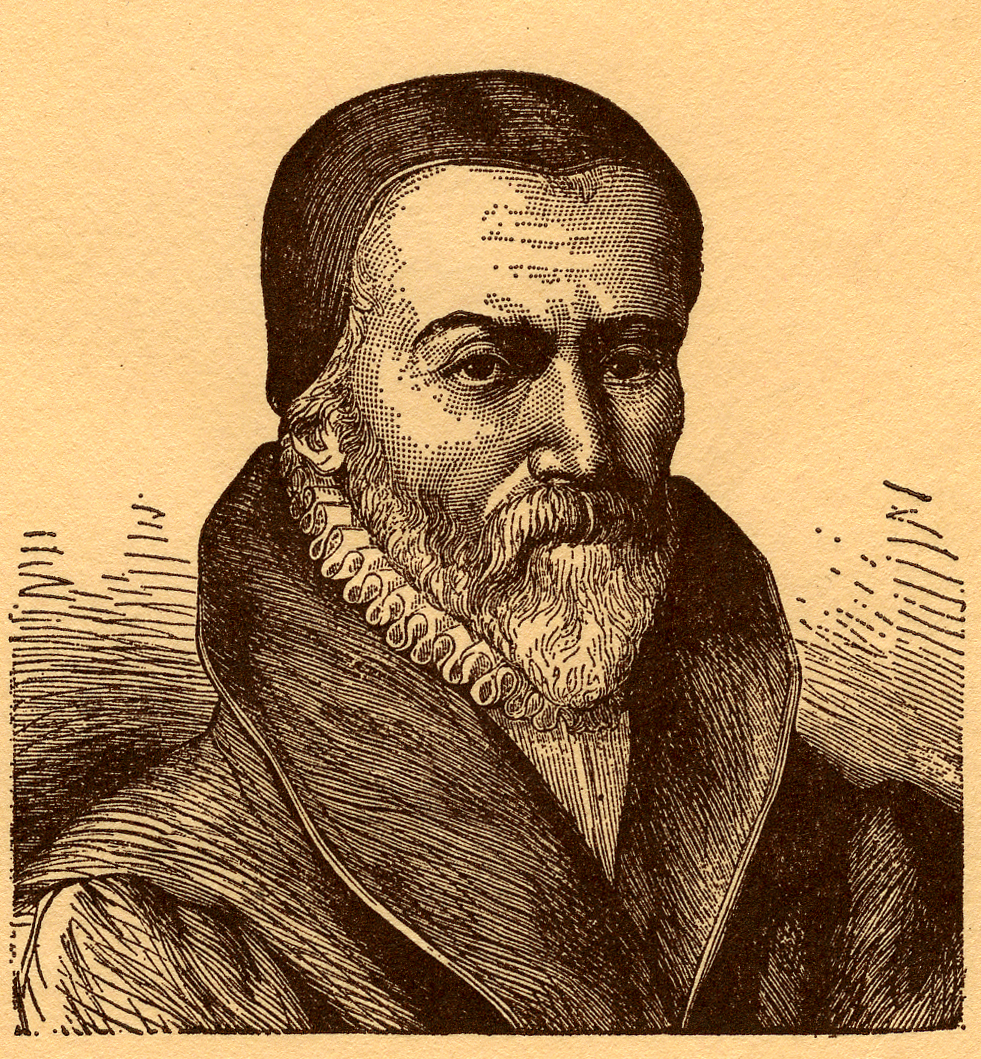

Biography

William Tyndale was born around 1494, probably in one of the villages near Dursley, Gloucestershire. The Tyndales were also known under the name Hychyns (Hitchins), and it was as William Hychyns that he was educated at Magdalen Hall, Oxford (now part of Hertford College), where he was admitted to the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in 1512, the same year he became a subdeacon. He was made Master of Arts in July 1515, three months after he had been ordained into the priesthood[citation needed]. The MA degree allowed him to start studying theology, but the official course did not include the study of scripture. This horrified Tyndale, and he organised private groups for teaching and discussing the scriptures[citation needed]. He was a gifted linguist (fluent in French, Greek, Hebrew, German, Italian, Latin, Spanish and of course his native English) and subsequently went to Cambridge (possibly studying under Erasmus, whose 1503 Enchiridion Militis Christiani — "Handbook of the Christian Knight" — he translated into English), where he is believed to have met Thomas Bilney and John Frith[citation needed].

He became chaplain in the house of Sir John Walsh at Little Sodbury in about 1521, and tutor to his children. His opinions involved him in controversy with his fellow clergymen, and around 1522 he was summoned before the Chancellor of the Diocese of Worcester on a charge of heresy[citation needed].

Soon afterwards he already determined to translate the Bible into English: he was convinced that the way to God was through His word and that scripture should be available even to common people. Foxe describes an argument with a "learned" but "blasphemous" clergyman, who had asserted to Tyndale that, "We had better be without God's laws than the Pope's." In a swelling of emotion, Tyndale made his prophetic response: "I defy the Pope, and all his laws; and if God spares my life, I will cause the boy that drives the plow in England to know more of the Scriptures than the Pope himself!" [2][3]

Tyndale left for London in 1523 to seek permission to translate the Bible into English and to request other help from the Church. In particular he hoped for support from Bishop Cuthbert Tunstall, a well-known classicist whom Erasmus had praised after working with him on a Greek New Testament, but the bishop, like many highly-placed churchmen, was uncomfortable with the idea of the Bible in the vernacular and told Tyndale he had no room for him in the Bishop's Palace[citation needed]. Tyndale preached and studied "at his book" in London for some time, relying on the help of a cloth merchant, Humphrey Monmouth. He then left England under a pseudonym and landed at Hamburg in 1524 with the work he had done so far on his translation of the New Testament, and in the following year completed his translation, with assistance from Observant friar William Roy.

In 1525 publication of his work by Peter Quentell in Cologne was interrupted by anti-Lutheran influence, and it was not until 1526 that a full edition of the New Testament was produced by the printer Peter Schoeffer in Worms, a safe city for church reformers[citation needed]. More copies were soon being printed in Antwerp. The book was smuggled into England and Scotland, and was condemned in October 1526 by Tunstall, who issued warnings to booksellers and had copies burned in public[citation needed].

Following the publication of the New Testament, Cardinal Wolsey condemned Tyndale as a heretic and demanded his arrest[citation needed].

Tyndale went into hiding, possibly for a time in Hamburg, and carried on working. He revised his New Testament and began translating the Old Testament and writing various treatises. In 1530 he wrote The Practyse of Prelates, which seemed to move him briefly to the Catholic side through its opposition to Henry VIII's divorce. This resulted in the king's wrath being directed at him: he asked the emperor Charles V to have Tyndale seized and returned to England[citation needed].

Eventually, he was betrayed to the authorities. He was kidnapped in Antwerp in 1535, betrayed by Henry Phillips, and held in the castle of Vilvoorde near Brussels[citation needed].

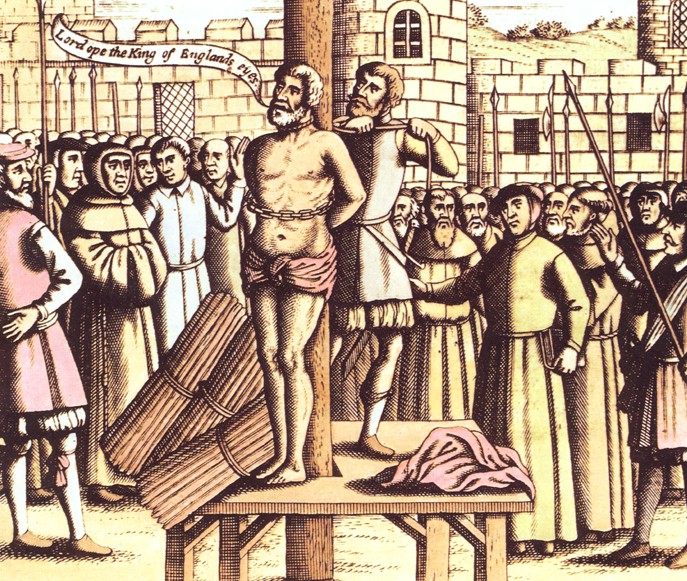

He was tried on a charge of heresy in 1536 and condemned to the stake, despite Thomas Cromwell's intercession on his behalf. Tyndale was strangled and his body burned at the stake on 6 September 1536[4] or 6 October 1536.[5] His final words reportedly were, "Oh Lord, open the King of England's eyes."[citation needed]

This was downloaded from Wikipedia in November 2007. My guess is that the citation needed insertions are a polite way of suggesting that behind the scenes there is a ding dong battle going on. Probably no finer tribute could be paid to anyone than to still be controversial more than 400 years after your death...