| Tom Pearce | = | Olwen (Kent) |

| b. August 3, 1909 | b. April 27, 1913 | |

| b. September 7, 1977 | b. April 4, 1983 | |

| Sweep | ||

| || |

| John Alfred | David Thomas | Robert Bryan | Geoffrey Alan |

| b. January 21, 1922 | b. October 7, 1924 | b. November 14, 1938 | b. November 20, 1946 |

| = June | = Jean | = Dorothy | = June |

| The Kents | The Williams | The Brinds | Rottenbury | Bewleys |

| Pearce family |

|

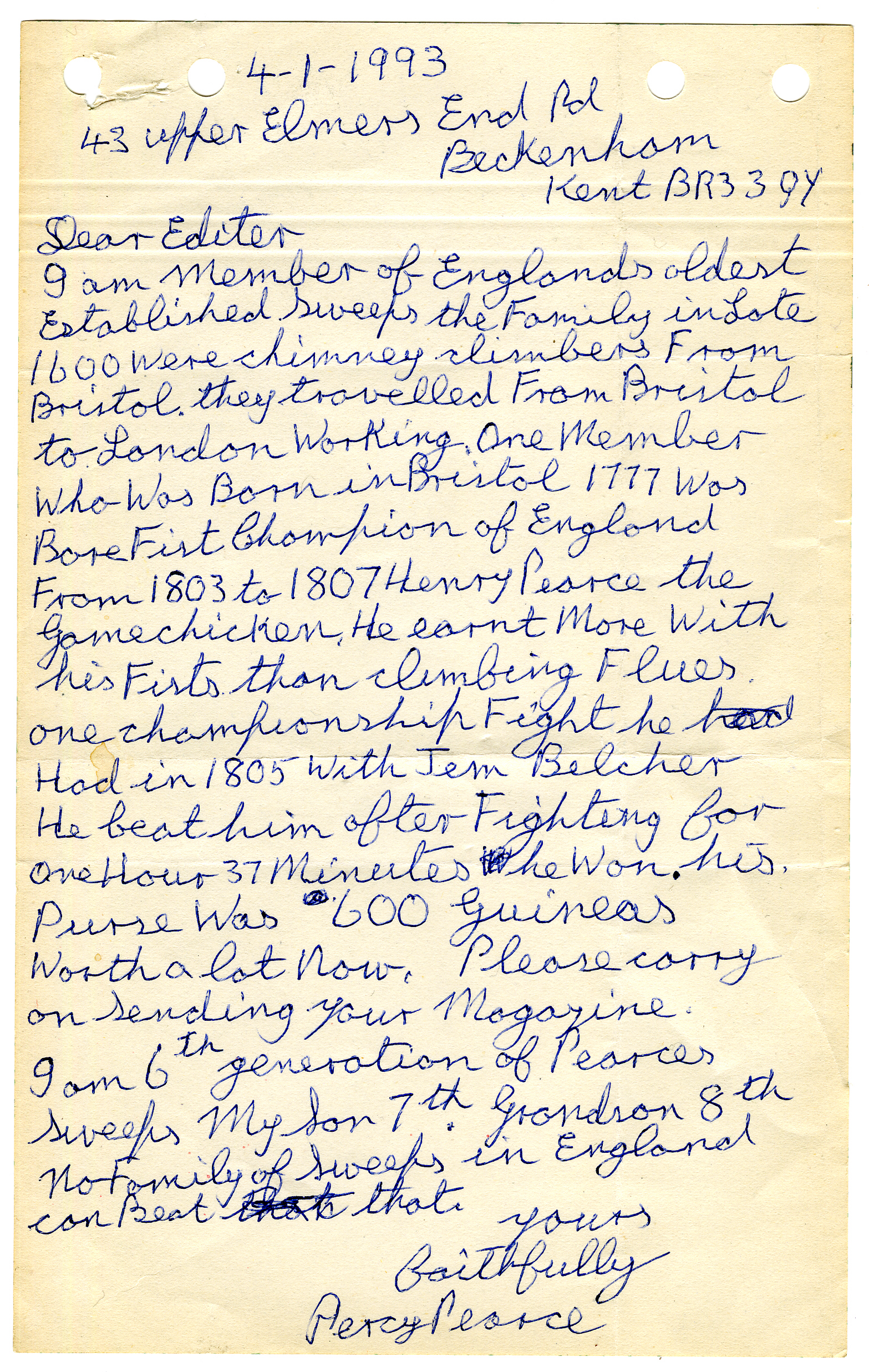

| 4-1-1993.

43 Upper Elmers End Road, Beckenham, Kent BR3 3QY |

| Dear Editor,

I am a member of England's oldest established sweeps family. The family in late 1600 were chimney climbers from Bristol. They travelled from Britol to London working. One member who was born in Bristol 1777 was Bare Fist Champion of England, from 1803 to 1807: Henry Pearce, the Gamechicken. He earnt more with his fists than climbing flues. One championship fight he had in 1805 with Jeb Belcher. He beat him after fighting for one hour 37 minutes. He won. His purse was 600 guineas, worth a lot now. Please carry on sending your magazine. I am a 6th generation of Pearces sweeps. My son 7th, grandson 8th. No family of sweeps in England can beat that. Yours faithfully,

This was sent to Jonathan Brind when he was editor of a magazine called Solid Fuel, read by coal merchants, sweeps, appliance distributors etc. |

|

Born: 1777

Died: 4/30/1809 Induction: 1993 Henry (Hen) Pearce The Game Chicken Although he did not possess the boxing skill of his immediate predecessor, Jem Belcher, Henry Pearce used his great strength and slugging ability to take the championship. Like Belcher, Pearce hailed from Bristol, England. Pearce started fighting in and around Bristol, although his first recorded bout is listed as having taken place in London in 1803 when he beat Jack Firley. In 1805, he fought a memorable battle with his friend John Gully, an inmate of debtors’ prison. The two staged a bout on the prison grounds with Gully getting the best of Pearce by a small margin. Impressed with his opponent’s showing, Pearce arranged for a sponsor to pay Gully’s debts so that he could be released from prison. The two then met in Hailsham for a public battle. Pearce dominated Gully early in the fight, knocking him down in each of the first seven rounds. In the eighteenth round, Gully came back to bloody Pearce badly. Two rounds later, one of Pearce’s eyes was almost swollen shut. The two fighters battled on, both bruised and bleeding. From the 33rd round until the end of the fight, Pearce controlled the action. After an hour and ten minutes, Pearce’s persistent attack sufficiently weakened Gully so that he could not continue. Pearce laid full claim to the title in his next fight, when he battled Jem Belcher. Although blind in one eye from an accident, Belcher agreed to the challenge. The slugging Pearce outfought Belcher for eighteen rounds to win the undisputed championship. Pearce never fought again. He toured the country after the Belcher victory, celebrating in high fashion. According to contemporary accounts, Pearce was drunk more often than sober. He contracted tuberculosis and other ailments and died in 1809, only four years after winning the championship. * * * Excerpted from 'The Boxing Register' by James B. Roberts and Alexander G. Skutt, copyright © 1999 by McBooks Press. All rights reserved. The 3rd edition of 'The Boxing Register' will be published in June 2002. Hall of Fame Roster, http://www.ibhof.com/pearce.htm |

| Henry Pearce |

| Henry Pearce was born in Bristol in 1777. He would fight as a boy in contests set up for bets by his father in local pubs and was, according to legend, never beaten. Belcher knew him and after his accident in 1803, brought Pearce to the capital in secret, presumably to pull off a betting coup when a championship contest materialised.

Belcher exhibited Pearce, who always signed himself Hen. and therefore earned the nickname ‘Game Chicken’, in front of a private circle of London friends against poor Jack Fearby in a ten-foot square bar at the Horse and Dolphin in Windmill Street. He won with gruesome ease and, we are told, blood spattered over each of the witnesses who were backed against the walls. The landlord, afraid that Fearby was dead, hired a woman to wash away the blood as quickly as possible. Pearce was given the bad-tempered butcher from Shropshire, Joe Berks, to beat up twice—in a room in August 1803, when Berks was under his breach of the peace order and therefore banned from fighting in public, and on a freezing Wimbledon Common in 77 minutes in January 1804. Berks said Pearce was a better fighter than Belcher. Pearce was a modest man, not given in those early days to enjoying too much company. After this second win over Berks he slipped away from the celebrations and was later found by his second Bill Gibbons in a pub in Chelsea, cooking himself mutton chops on the open fire. He also defeated a Bristol coppersmith named Elias Spree or Spray in 35 minutes at Moulsey (now usually spelled Molesey) near Hampton Court in March 1805, after which he heard his old Bristol friend, John Gully, was locked away in Fleet Debtors’ Prison. He was determined to do something about that, but beforehand disposed of Stephen Carte of Birmingham on 27 April 1805 in front of a large near Chertsey, a Surrey village on the banks of the Thames. The multitude included men and women of fame, notoriety and reputation. There was Alicia Massingham, mistress of Colonel Thornton, and the remarkable Lady Lade, who had been the lover of both highwayman ‘Sixteen String’ Jack and The Duke of York before she settled down to marry Sir John Lade; and also there was the Duchess of Bedford, who had made her reputation by admitting to her husband gambling debts of £176,000. Lord Eardley brought along his mistress, Bella Prior. After disposing of the outclassed Carte, Pearce sat on a bale of straw to watch Tom Belcher fight Jack O’Donnell and the great lightweight Dutch Sam win a marvellous battle with Bob Brettle. Pearce’s greatest victory was against his acquaintance from his Bristol days, John Gully. He had staged an exhibition with Gully in debtors’ prison, as a result of which a sporting gentleman named Fletcher Reid had settled Gully’s debts and obtained his release. Gully and Pearce fought for real at Hailsham, Sussex, which was then a small village on the Sussex Downs, on 8 October 1805, Pearce winning a magnificent battle in 64 rounds lasting 77 minutes. Because the men knew each other so well suspicions of a ‘cross’ had been rife in London, and the fight had already been postponed once, but Gully performed so well that by round 20 Pearce was cut and almost blind in his left eye. However in the 23rd Gully was caught as he fell by a tremendous blow on the side of the head. As he lay on the ground Gully vomited. It was obvious from that point on that he could not win, and yet his courage kept him coming back up for more. The last blow landed on Gully’s throat and he was temporarily unable to breathe. At the back of the crowd of 10,000 people, the Duke of Clarence, later William IV, watched from a horse. On the same day, at the same place, Tom Cribb beat the first of the great black fighters, Bill Richmond, in 90 minutes. The Game Chicken’s last fight was his merciful battering of Jem Belcher, but by then his own health was giving rise to concern. His marriage was a disaster, his wife was ‘a shameless and abandoned woman, who embittered his life and ruined his home’, according to Egan, who may have been prejudiced. Egan blamed this woman’s ‘infidelities’ for Pearce’s eventual, fatal dependence on gin. Whatever the cause, he sank quickly. A Leicestershire man named Ford boasted he would beat Pearce for a glass of gin, but the champion wasn’t in town at the time. The incident probably meant little in itself, but was indicative of the swinging of opinion. By 1807 he was a drifter giving exhibitions from town to town, with a new wife in tow. In Bristol he seemed for a while to be living more temperately and on Clifton Downs he gave a hiding to three gamekeepers named Hood, Morris and Francis, whom he found ‘insulting’ a woman. In the town itself in November 1807, he also rescued a servant-girl who was trapped in the attic of a burning shop, belonging to a silk mercer named Mrs Denzill, in Thomas Street. His heroism was commemorated by a local journal: ‘Oh, glorious act! Oh, courage well applied! Oh, strength exerted in its proper cause! Thy name, 0 Pearce! be sounded far and wide, Live, ever honoured, midst the world’s applause; Be this thy triumph! Know one creature saved Is greater glory than a world enslav’d.’ But by 1808 the dreadful, blood-flecked coughs of tuberculosis had set in. It was sheer folly to travel to Epsom Downs from Oxford to watch Beicher fight Tom Cribb in the mid-winter, but he did. Afterwards the 15-mile freezing journey to London, to a friend’s pub, the Coach and Horses in St Martin’s Lane, broke his resistance. He could barely walk unaided when a benefit was held for him on 11 April 1809. Only 19 days later he was dead. He was 32. He was buried, as he had asked to be, next to Bill Warr, who had boxed Daniel Mendoza three times 20 years before and who had only recently died of consumption. The two of them lay in St James Churchyard, St Pancras. Pugilistica recorded that he went bravely to his death, without terror, ‘expressing a wish to die in friendship with all mankind’. Pearce’s epic struggle with Gully in Sussex had taken place just a fortnight before the Battle of Trafalgar, in which the British fleet lost Horatio Nelson but defeated the combined Spanish and French navies. It was a euphoric time. And it seemed that just as England ruled the waves, and therefore the world, England’s prize-fighters reflected and symbolised its greatness. Gully, Pearce, Belcher and Tom Cribb became national heroes. http://weldgen.tripod.com/fighters-of-the-west-country/id6.html |