|

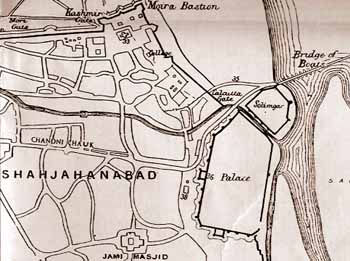

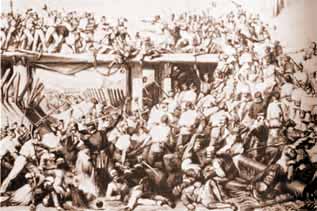

Delhi had once been one of the most splendid cities in the world. Capital of the Moghuls, it had been home to great emperors who ruled India from the sandstone and marble splendour of the Red Fort. Times had changed and the days of Moghul power were now no more than a folk memory. In 1857 Bahadur Shah, the last of the Moghuls, was a pensioner of the British who still lived inside the Red Fort and maintained the pretence of former glory by continuing the ceremonial functions of the Moghul court. Old and white-bearded he was an accomplished poet who had no interest in regaining the power that had belonged to his forebears. Indeed Delhi had become a place of such little consequence to the British that they no longer even bothered to station European troops there. Delhi was garrisoned by three regiments of native infantry. There was however a small European community and Bahadur Shah's personal guard was commanded by a British officer, Captain Douglas. It was to this city that the mutineers fleeing from Meerut came. All night as they rode down to Delhi they had anxiously listened for the sound of pursuit, but none came. Perhaps the British were so shocked by what had happened that they were unable to instantly react. Perhaps they feared for the safety of the remaining women and children in Meerut. Whatever the reason, the only chance of containing the mutiny had been lost. Already the mutineers had British blood on their hands and knew they would receive no mercy if captured. Their only hope now was to create a general rising that would drive the British out of India completely and they turned to Bahadur Shah to lead them. On the morning of 11th May the bridge of boats that carried the Meerut road across the Jamuna River into Delhi rattled with the sound of the mutineers' horses' hooves. Gathering below the walls of the Red Fort, the mutineers called for Bahadur Shah. From the walls high above Captain Douglas ordered them to disperse. It was an order not likely to be obeyed and an hour or so later the sepoys again accompanied by a mob from the bazaar burst into the palace, murdered Douglas and four other Britons (two of them women) and begged Bahadur Shah to reclaim his patrimony. Bahadur Shah was appalled by the wild mob carousing in his palace and had sent messengers to the British garrison at Agra asking for help. None came and the old man finally gave in, accepted the allegiance of the mutineers and became the titular leader of the Indian Mutiny. Most of the Europeans in Delhi were murdered along with Indian Christians. Some managed to escape the city only to be killed by villagers or brigands on the roads to Meerut or Agra. |

|

The loss of Delhi was a crushing blow to British prestige and the symbolic associations of the capital of the Moghuls being the centre of the mutiny were something the Britsh could not ignore. Only Delhi had the aura of authority that could provide any serious focus of resistance to British rule. From Meerut and Simla two British columns set out for the capital. Hampered by lack of transport, it was weeks before they joined forces at Ambala. Punishing disloyal villages as they advanced, one could have charted their course by the scores of corpses they left hanging from trees along their line of march. At Badl-ke-Serai, five miles from Delhi, they met the main army of the mutineers and though the British won the field they failed to destroy the sepoy army which fled back to the protection of the walls of Delhi. The British established themselves on Delhi ridge, a thin spur of high ground to the north of the city. There, two months after they had been forced out of the city, the British once again looked down on the massive ramparts of the capital of the Moghuls.

Fortuitously for the British, to the west of Delhi, the Punjab under

the control of John Lawrence had stayed quiet and a flying column was

swiftly organised. It was placed under the command of John Nicholson, one

of the great paladins of the British experience in India. Over six feet

two inches tall, fiercely Christian, with burning blue eyes and almost

certainly a repressed homosexuality, Nicholson was already a legend in the

north-west. He was alternately loved and feared by the Sikhs of the Punjab

and the wild tribesmen of the north-west frontier. Mothers would use his

name to frighten their children to sleep and it was said that the sound of

his horses hooves could be heard from 'Attock to the Khyber'.

After they came, the siege didn't last long. Twice the British breached the great walls only to see their badly outnumbered assault forces thrown back by the sepoys. Finally, a breach was made in the Kashmiri Gate and led by Nicholson this time the attackers were not checked. They swarmed into the city and after a week of bitter street fighting in the narrow streets and alleyways they forced their way through to the open ground in front of the Red Fort. The fort was deserted, Bahadur and his sons having fled to the imagined safety of Humayun's tomb on the outskirts of the city. British officers ate their dinner that night in the marbled mosques and great audience hall of the old king. Delhi was again British. Only one thing had marred the triumph. In the attack on the Kashmiri gate Nicholson had been hit by a mutineer's bullet and died soon after. Most of his men having sacked the city as promised shouldered their loot and headed home. They had come, they said, for Nicholson and not to fight for the British. With his death their service was over.

One last atrocity was yet to happen. William Hodson, the son of an

English clergyman, was intelligence officer for the British force and he

was detailed to arrest Bahadur Shah. A wild leader of irregular cavalry,

he took his squadron of Sikhs out to Humayun's tomb, arrested the old man,

promised him his life but threatened to shoot him out of hand if there

were any attempt at rescue. Hodson later described the ride back to Delhi

as the longest in his life. The palanquins carrying the king and his party

moved only at a slow walking pace and Hodson's Sikhs were vastly

outnumbered by the crowd that came to watch the mournful procession.The

following day Hodson rode back to the tomb and arrested the king's three

sons, Mizra Moghul, Mizra Khizr Sultan and Mizra Abu Bakr. Just before

reaching the walls of Delhi, he ordered them out of the bullock cart they

were riding in, stripped off their clothes and with his own hand shot the

three of them dead. Their bodies were dumped on a midden heap outside a

Delhi police station. Hodson claimed in a letter to his brother, Rev.

George Hodson, that he killed the princes because the mob following were

about to attack his troopers. He described the situation thus - "I came up just in time, as a large mob had collected and were

turning on the guard. I rode in amongst them at a gallop, and in a few

words I appealed to the crowd, saying that these were the butchers who had

murdered and brutally used helpless women and children, and that the

government had now sent their punishment : seizing a carbine from one of

my men I deliberatly shot them one after the other...the bodies were taken

into the city, and thrown out on to the Chiboutra in front of the

Kotwalie... I intended to have them hung, but when it came to a question

of "They" or "Us", I had no time for deliberation."* Perhaps this is true, but we have to ask ourselves whether the son of a clergyman writing to his clergyman brother would ever admit to being a cold-blooded murderer. Hodson was a man often compared to the condottiere of the 15th century and had once been accused of embezzling the mess funds of his own regiment. It also seems unlikely that the mob would have waited almost until the procession reached Delhi before taking action; they had traversed miles of open country on the journey where a rescue attempt would have been much easier to effect. Whatever the reason for Hodson's action, his behaviour that day was disgraceful and can only be described as murder. Bahadur Shah was tried for complicity to murder and other offences,

found guilty and sent into exile in Rangoon. He died there in 1862, the

last of the Moghuls. Hodson was never punished for his summary executions

of the princes. He died in the retaking of Lucknow in 1858. *My thanks to Daniel Elliot for sending me the above quote from Hodson's letter |