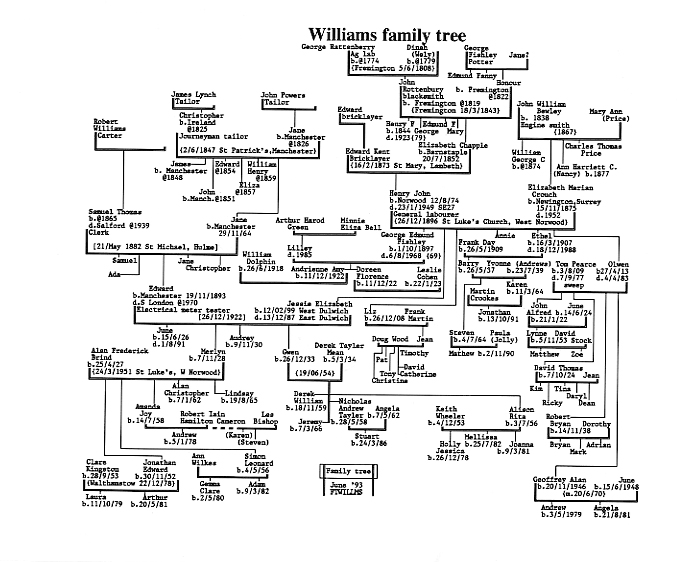

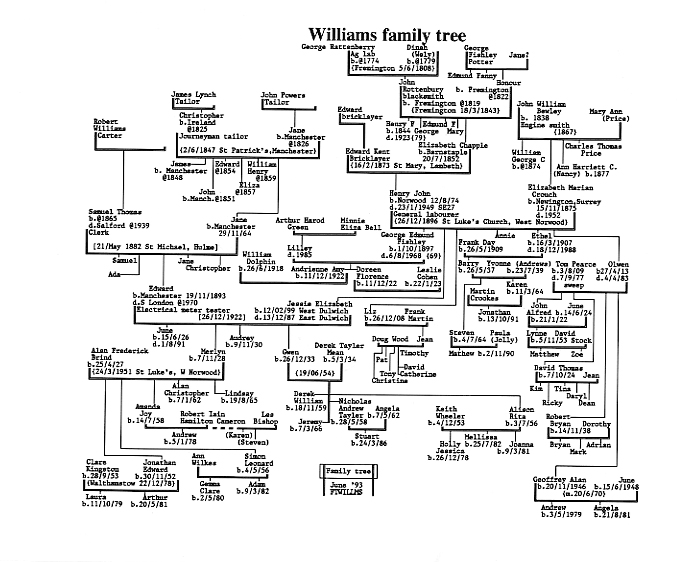

| The Kents | The Fishleys | The Brinds |

| 1830/40s |

| Christopher Lynch was born in Ireland, Jane Powers in Manchester, but she was almost certainly of Irish descent. They married at St Patrick's Catholic Church in Manchester and according to their wedding certificate both their fathers (James Lynch and John Powers) were tailors. Christopher was also a tailor. Jane seems to have worked as a binder before she was married, though her occupation on the wedding certificate is hard to read.

James Lynch (father of Christopher) came over to Manchester some time before 1841. He was living at 29 Cable Street with his wife (hard to read but could be Roisin?). They were both aged between 50 and 55, when the 1841 census was taken. The wife had no occupation. Christopher, then aged about 18, was already working as a tailor, as was John, 13, probably his younger brother and like Christopher born in Ireland. The 1841 census for 29 Cable Street also mentions Mary Ann Lynch (aged between 20 and 25), almost certainly Christopher's older sister, also born in Ireland. She may be the Mary Ann Kiernan who with Patrick Kiernan witnessed Christopher Lynch and Jane Powers wedding. Jane Powers gives her address as Hatters Lane, Manchester, but at present I have been unable to find them in the 1841 census. Jane Lynch, named after her mother, was probably the youngest of Christopher and Jane's children. She was born on 29 November 1864, at 29 Dolefield, Manchester, when her mother would have been aged about 39. She was probably never educated, though she seems to have learnt to write her signature at least, since she signed her name when she got married. |

|

There is not, I believe in Manchester or Salford a single free school for girls of the working classes. There are girls whose education is assisted, their parents paying a part of the expenses, and I doubt not there are a few in different schools who are paid for entirely by benevolent individuals. But these are so few as to be practically out of the calculation, when we consider the many thousands who are not receiving any education. In a poor family with three or four children, when the income will not admit of the schooling of all, of course the boys get the preference. It is a general feeling that as the boy has to go out and wrestle for his life with the worst, education is far more necessary for him than for his sister, to whom it is looked upon rather as an accomplishment, desirable, but not indispensable. It is evident that, in a town like Manchester, the neglected education of girls is fraught with the most disastrous consequences. Great numbers of the present mothers of families have, almost from childhood, been compelled to earn their own livelihood in mills, workshops and warehouses. Very often, when one of this class marries, she cannot read, or can read only so imperfectly that the effort is painful to her and gives her no intelligible ideas. She cannot sew, she cannot wash, she cannot cook. When she first attempts to clean up her little house, her cleaning is what an old fashioned Lancashire housewife would call 'cat-licking'. She is improvident for the simple reason she has never learnt what calculation and forethought are. She marries as other people would take a day's holiday. Her wedding is a pleasant little incident in her life and the next day she goes to her work as usual. With the children her troubles begin. The wife's income becomes irregular or ceases; there is sickness, poverty, discontent and often quarelling. The husband comes tired to his cheerless, dirty, unfurnished home in a dingy street. Both he and his wife feel something is wrong, but neither of them know what. One blames the other and then the husband seeks refuge in a beeerhouse.

Manchester Guardian, January 16, 1864. |

| 1880s |

| Christopher and Jane had moved again, to 24 Dearden Street, Hulme, Manchester, by the time the 1881 census was taken. He was 56, she 54 and they had two children living with them: William Lynch, aged 22, a warehouseman and 16-year-old Jane, a dressmaker born in Manchester.

This was the address Samuel Thomas Williams gave when he married Jane Lynch, while Jane gave her address as 17 New Street, which is just round the corner. At that address in 1881 there was a widow called Hannah Harrison (48), born in Manchester, who had three children Robert Harrison (22), Mary Harrison (16) and Amy Harrison (8). Perhaps Mary Harrison was the Mary Jackson who was the witness for Jane Lynch when she married? The wedding of Samuel Thomas Williams, who was born in Liverpool, and Jane Lynch, aged 17, took place at St Michael, Hulme, a Church of England Parish Church on May 21, 1882. Samuel gave his age as 19 (though he was probably 16 or 17). He said he worked as a Clerk. His witness was James Williams (brother, uncle?) and he said his father Robert Williams, a carter, was dead. Nine years later the couple were living in a two up, two down house at 29 Arthur Street, Hulme, with children Christopher (6), James (4) and Ada (1). Samuel was working as Clerk in the Dyeworks and according to the census he was younger than his wife. He was 25 and she 26. Poor little James was suffering from 'Water on Brain', according to the 1891 census. Edward Williams, my grandfather, was born on November 19, 1893. The family were still living at 29 Arthur Street but Samuel Thomas may have gone up in the world. At any rate he had a fancier job title. He was described as a 'Commercial Clerk'. Jane Williams, who according to family legend had bright red hair and spoke with a broad Irish accent, probably died in the early 1930s aged about 65. Edward Williams my grandfather, was a Meter repair tester. His health was never very good after the First World War. He had a struggle keeping himself on his feet to go to work. |

|

| The Rottenbury (or Rattenberry) family evidently originate from North Devon. In Victorian Devon there were hundreds of Rottenberrys (using almost as many different spellings of the name). Elsewhere there were precious few.

The earliest known family marriage involving a Rottenberry recorded on a certificate was between John Rottenbury and Honour Fishley on March 18, 1843. They were both at least 21, John may have been 24, Honour was probably a couple of years younger than him. They married in their local parish church in their home town, Fremington, a short distance from Barnstaple. This was probably the same church in which John's parents, George Rattenberry and Dinah Wely had married, 35 years earlier. By the way fancy changing your name from Wely to Rattenberry? The two witnesses when John and Honour married were Edmund Fishley, probably Honour's brother or uncle, and Mary Rottenbury. Both John and Honour could write. He was a blacksmith, she a bonnet maker. In 1841, before Honour married she was living with her grandfather, a potter called George Fishley, who was aged about 70 when she was about 15. According to Honour's wedding certificate her father was also a potter called George. Also at the same address as Honour and George when the 1841 census was taken was a Jane Fishley, aged about 60, and a Fanny Fishley, aged about 20. Fanny was probably Honour's sister, Jane may have been her grandfather's second wife? The Rottenburys and the Fishleys probably had very close ties. They lived almost next door to each other in a village which was, in any case, very small. By 1901 the population of Fremington was only 1,194. Not far from Fremington is the even smaller village of Milton Damerel (population 442 in 1901). In this tiny place there were at least two Rattenbury/Fishleigh marriages in the 50 years before John and Honour married. Alice Rattenbury & Francis Fishleigh in 1829 and John Rattenbury and Mary Fishleigh in 1795. Fremington was full of Rottenberrys, Fishleys and Chapples. Fishleys had been living in the village since at least 1614, Chapples since at least 1636 and Rottenberrys since at least 1739. My guess is that Honour's mother's maiden surname was Chapple. There was certainly a Fishley/Chapple marriage in Fremington: Elizabeth Fishley married Thomas Chapple on April 2, 1826. Early in 1993 the Museum of North Devon in Barnstaple, had an exhibition of pots made by Fremington Pottery. This pottery, it turned out, had been owned by the Fishleys. The display said: " The Fishleys of Fremington. Members of the Fishley family worked at the Fishley pottery from the early 1800s until 1912. Their normal production was quite plain and utilitarian but it was traditional for a potter to undertake special work such as wedding pieces, pocket watch stands and harvest jugs for local farmers and some pieces were made for their own satisfaction |

| George Fishley | 1771-1865 |

| Edmund Fishley | 1806-1860 |

| Robert Fishley | 1808-1887 |

| Edwin Beer Fishley | 1832-1912 |

| After 1912 the Fremington pottery was sold to a Staffordshire potter, Ed Sadler, who after a few years sold it to Brannam's." The museum refers to "50 years a potter" by W Fishley Holland published by Pottery Quarterly in 1958. This book, written by a distant cousin, gives the flavour of life at the Fremington pottery nearly 100 years ago. For extracts from the book see appendix 1.

Fremington had its own quay and probably exported pottery all over the world. The patriarch George Fishley is almost certainly the George Fishley who was Honour's grandfather. In Fremington Village & Pill, a self-guided trail, there is a copy of a painting of the old Fishley pottery (courtesy of the North Devon Atheneum Barnstaple photographed by the Museum of North Devon. It looks like a lean to attached to a giant bee hive. The guide reveals: "Morris's Commercial Directory and Gazetteer of Devonshire of 1870 carried an advertisement for "Edwin B Fishley, manufacturer of all kinds of red earthen ware, seed pans, sea kale, rhubarb, garden and chimney pots'. Pipes, pitchers and ovens were also made, much being sent to Cornwall. The decorative ware was noted for its rich colours (examples can be seen in the Museum of North Devon in Barnstaple), and harvest jugs were a speciality. The clay is stone-free and needed to be kept clean before it was used for such items. Coarser wares required the addition of grit or gravel to the clay. "Fuel costs were high, but the clay was relatively cheap. In 1900, six men and an apprentice worked here, most of the throwing being done by the master. The others each had specific tasks. Production at this pottery finally ceased about 1930." There are several George Fishleys mentioned on the tombstones in the Fremington Parish Church Cemetery. The relevant inscriptions read: "Sacred to the memory of Mary wife of George Fishley of this parish who departed this life the 21st day of April in the year of our Lord 1859. Aged 61 years." And: "Sacred to the memory of George Fishley of this parish who departed this life January the 22, 1838 aged 57 years. Be merciful unto me oh God for my soul most trusteth in thee therefore under the shadow of thee thy wings shall be my refuge..... Also to the memory of George the son of Edmund and Dorothy Fishley of this parish who departed this life March the 26th 1839 aged 5 months." |

| Edmund was probably Honour's uncle. In 1841 he lived at Muddlebridge, Fremington, was aged about 30 and like his father was a potter. His wife was Dorothy and his children were Mary, 11, and Edwin, 9.

John and Honour lived a few houses away from each other at Bickington in 1841, when the census was taken. John was still a blacksmith's apprentice, Honour was working as a bonnet maker. Just down the road and still in Bickington in 1841 was a Henry Rottenberry, a journeyman mason in his mid 20s. He may well have been John's brother. John certainly called his first son Henry, suggesting a common Henry Rottenberry ancestor. Henry was married to Fanny, though not Fanny Fishley, she was still living with her parents. Henry's wife was a lace maker. It seems extraordinary that the wife of a journeyman mason should need to work. Henry and Fanny had two children, Eliza (7) and Henry (3). Also in Bickington in 1841, lived George Rottenberry, in his mid 40s and also a mason, with his wife Rebecca and daughters Susan, 15, Joseph, 14, and Jane, 10. George and Rebecca are buried in the Fremington church yard. Their headstone says: "Sacred to the memory of George Rottenberry of this parish who departed this life June the 8th 1851 aged 56 years And in my prosperity I said I shall never be removed. Psalms XXX 6 V. Also to the memory of Rebecca wife of the above George Rottenberry who departed this life January the 7th 1864 aged 76 years also to the memory of George Daniel the son of George Rottenberry and Elizabeth his wife of Barnstaple Draper who departed of this life January 5th 1853 aged 8 months." In North Lane, Fremington, lived William Rottenbery, also in his 20s and another mason, his wife Mary and son William (2), in 1841. Robert Fishley, a potter's labourer, and his wife Jane, lived at West Combrew, Fremington. Their household in 1841 included a six year old girl called Mary Rottenberry. How Mary fits into the picture is impossible to say. Perhaps she was an orphan though why she was living with the Fishleys is a mystery. One of the clues which suggests a Chappell connection is that a second Mary Rottenberry, aged 15, was a servant in the household of William and Elizabeth Chappell in 1841. He was in his mid 70s, she perhaps 15 years younger. He was independent, or in other words a pensioner. A William Chappell married an Elizabeth Crocker on the 28th August 1817, in Fremington. In Brookfield, Fremington, in 1841 lived Mary Chappell, aged about 90, and described as independent. She seems to have been a part of the household of a clay merchant called Stephen Crocker. Mary might have been the wife of Samuel Chappell and the mother of John, Mary Elizabeth and Samuel, all Christened in the 1780s. |

| John Saml Chappel/Mary | 06/01/1782 |

| Mary Ann Saml Chappell/Mary | 29/10/1783 |

| Elizabeth Saml Chappell/Mary | 29/05/1785 |

| Samuel Saml Chappell/Mary | 12/09/1786 |

| The biggest clue that the Chappell family are relatives is that John and Honour named their daughter Elizabeth Chapple. Chapple is such an unusual forename that it seems clear they were giving her Honour's family name.

Elizabeth Chapple Rottenbury was born in 1852 in Maiden Street, Barnstaple, where John and Honour had moved. This was probably a road close to Barnstaple Bridge. Three arches of the bridge (the ones closest to the town) are called the Maiden Arches. In early 1993 I walked down Maiden Lane, a small alleyway with an open drain running down the middle of the road. There must be about a dozen restaurants in it. Few if any of the houses show any sign of being more than a century old. In 1851, when the census was taken, John & Honour were living in Maiden Street with their children Henry, 7, George, 5, Edmund, 3, and Mary, 1. John was a blacksmith, Honour's occupation was blank. Perhaps she had given up bonnet making? John and Honour moved to Barnstaple soon after marrying and all the children were born there. The family next moved to the London area, perhaps John was seeking work. John probably died in 1856, in Greenwich. In the first quarter of 1859 Honour married again in Lewisham. At present I do not know the name of her husband. On the 16th of February, 1873, Elizabeth Chapple Rottenbury married a bricklayer called Edward Kent, himself the son of a bricklayer called Edward Kent. They married at St Mary, Lambeth. Edward Kent signed his name, Elizabeth made her mark. The Rottenbury family probably couldn't afford to pay for the education of a girl. Elizabeth's brothers had already married. Henry Fishley Rottenbury married in the last quarter of 1865 in Lambeth, perhaps the same church as Elizabeth married in? Edmund Fishley Rottenbury married in Camberwell in the first quarter of 1872. In the last quarter of 1891 a death certificate for a one year old girl named Jessie Annie Rottenbury was issued in Greenwich. It seems likely she was the child of Henry Fishley or Edmund Fishley Rottenbury, since Jessie and Annie are both family names. The third brother, George F (presumably Fishley), may not have married. He appears to have died in Lambeth in the first quarter of 1897 at the age of 51. Henry F died in the second quarter of 1923 (aged 79) and Edmund F died in the last quarter of 1925 in Reigate aged 77. Not much is known about the Rottenberrys after that time. Except Andrienne Dolphin, daughter of George Edmund Fishley Kent, said her father had joined the Coulsdon Freemason's Lodge because his cousin Edwin Rottenberry had been a member. Edwin, she recalls, lived near Emmanuel Church, Clive Road, Norwood. But there are two Rottenburys in the London telephone directory (in 1993). |

| Rottenbury J, 54 Windsor Clo, SE27 9LX |

| Rottenbury Miss N, 20 Landford Rd, SW15 1AG |

| Andrienne's father was always called Fish by her brother in law Leslie Cohen. When they went to Spain the nickname changed to Piscardo. But she did not know about the history of the Fishley family.

On the 12th of August 1874 Elizabeth Chapple and Edward Kent had a son, Henry John Kent, who was born at 1 Prospect Villa, Gipsy Road, Norwood. Gipsy Road is where my parents were living when I was born, though I was actually born in King's College Hospital. The family appears to have moved from Prospect Villa before the 1881 census was taken and at present I don't know if Henry John had any brothers or sisters. Henry John Kent married Elizabeth Marian Crouch Bewley on Boxing Day 1896 at St Luke's Church, West Norwood. Their son George Edmund Fishley Kent was born on the 1st of October in the following year. My grandmother, Jessie Elizabeth Kent, was born on the 12th of February 1899, possibly at Romany Road. "At one stage they all lived in Romany Road," my Mum told me. "I have got a strong feeling my mother was born in Romany Road." Jessie had several sisters including Liz (born on Boxing Day, 1908, her parent's Wedding Anniversary), Annie, Ethel and Olwen (born on April 27, 1913). Edward Williams met his wife to be, Jessie Kent, at TMC (Telephone Manufacturing Company) in Tritton Road, a turning off Clive Road. They both worked there during the First World War. "My Dad had been invalided out of the army and my Mum was working there," my Mum told me. "Half the people in Norwood worked there at one time. My Mum was putting Dope (possibly a cellulose type paint) on the wings of aeroplanes. My Dad was always very good with his hands. He may have been involved in aeroplane making." Mum doesn't know how her father met her mother but says: "Mum was the eldest of four or five girls. There was always a crowd of them." Perhaps they just met up, she suggests. Edward & Jessie courted for a long time before they got married and they were married for four years before they had their first daughter, June. Jessie Kent's father tried to talk her out of marrying Edward Williams because of his health. Doctors said Edward only had about a year to live. "She said 'never mind if I can have him for a year, I will'," my Mum told me. Edward & Jessie moved in with her parents at 57 Clive Road. The tenancy was in the name of Henry John Kent. My Mum says: "When grandfather died, which was just before we were married, they swapped the lease to grandmother. When grandmother died they wouldn't swap the tenancy again so mother and father were evicted. They got a flat in Canterbury Grove through the council because the council had taken over unoccupied premises. They (her parents) were actually council tenants though it wasn't council property and they were there till my father died." Mum remembers her grandmother, Elizabeth Marian nee Crouch Bewley as what they called a wise woman. "She had been taught it by her grandmother," she said. This wisdom was a knowledge of folk medicine. She would sometimes go out and nurse people. Mum also remembers her making toffee apples and cocounut ice for the children. "She was very good to us," she said. Clive Road only had an outside loo (a privy) and no bathroom. The plumbing was extremely basic and there was no running water upstairs. "My father paid for the electricity to be put in," said Mum. "We had gas only until I was about 10. ...the landlord point blank refused to do anything." The agents, who may have been Montague F Long or Veriyard & Yates, claimed that they had no power to do anything but collect the rent because the property was in Chancery, the subject of a dispute about a will. The rent was 15s a week. "Bear in mind my father was earning about £3 so it was a considerable rent," said Mum. The house no longer exists. It was demolished in the 1980s or early 1990s. Mum lived there from the day she was born until she got married, except when she was evacuated during the war. "I was only about 12 if that," she said. "We went to Ditchford in Gloucestershire... June must have been 14 and they wouldn't let her go to (the local school)...I went there for a while... Ditchford was a tiny hamlet, consisting of a farm, a pub and a few cottages. They lived in one of two cottages in the middle of a field. Mum recalls that they got billeting money, so it wasn't totally unauthorised. "My uncle Tom found an empty cottage in the middle of a field," she said. "My Aunt Olwen and the three boys they had then, and my mother went down by train and then we got a lift from the station (Moreton in the Marsh) on a big lorry." There were two women and seven small children in a cottage which had no water, no electricity, no gas, no anything. "We had to pump the water," she said. "The pump was on the sink in the house." "The funny thing is that the people who lived in the next door cottage, their name was Kent," Mum said. "They were evacuees too." The Education authorities were not happy about the arrangement saying that June should have been attending school at Stratford on Avon. "The education authority said they would give us bicycles but my mother said no way would we bicycle 14 miles there and back," Mum says. "So we were then sent to Reigate." At Reigate there was a proper Grammar School but they didn't get on with the locals. Mum says they were "too insular". "They didn't like us being there," she said. "They used to call us 'them refugees'. They wouldn't let us have sweets in the shops. They used to say 'they're for local children'. "The people I stayed with the woman was a bitch, (Mrs Snashfold). She hated kids. She didn't want any and she didn't want us." Honour Oak, the West Norwood school, moved to Reigate County Girls where the two schools shared facilities. Both schools had to offer part time education. "We had to go all day Saturday and got all day Monday off," Mum said. "In summer we used to have a lot of lessons out on the grass." Later the school took over a large house called Rosemead and the evacuees went there for lessons. Mum became ill: "I was taken to hospital and when I came out of hospital my mother came and took me and I went home and then June moved in and stayed the rest of the war. They said I was suffering from malnutrition... I was the thinnest girl in the school in those days... I used to pass out in lessons... we were so appallingly badly fed... they would give us a bowl of cereals for breakfast and then they'd give us bread and jam for tea and of course we had disgustingly awful meals (for lunch) it was uneatable." The people who were supposed to look after them thought they were getting a proper meal at lunch and therefore skimped on the other meals. When Mum returned home she went back to her own school now run as the South London Emergency School. "I stayed there until I was 17," she said, "when we had the buzz bombs and the rockets... I did school certificate during a buzz bomb raid, doodlebugs... We spent more time in shelters than we did in the classroom we became experts at all the pencil games." The shelter was a bricked up classroom on the ground floor which had been made as safe as it could be. After the sisters returned home the school transferred from Reigate to Ebbw Vale but their mother wouldn't hear of them going there. Audrey passed her scholarship and started at Honour Oak and Gwen followed, though that may have been after the War. "There had been other families where four had passed but we were the first family where all four had passed the scholarship and there were only the four," she said. "There was a bit in the paper, my mum kept it for years." June made the front page of the Norwood Press and Dulwich Advertiser of January 24, 1941, with a letter she sent home. |

| 1940s |

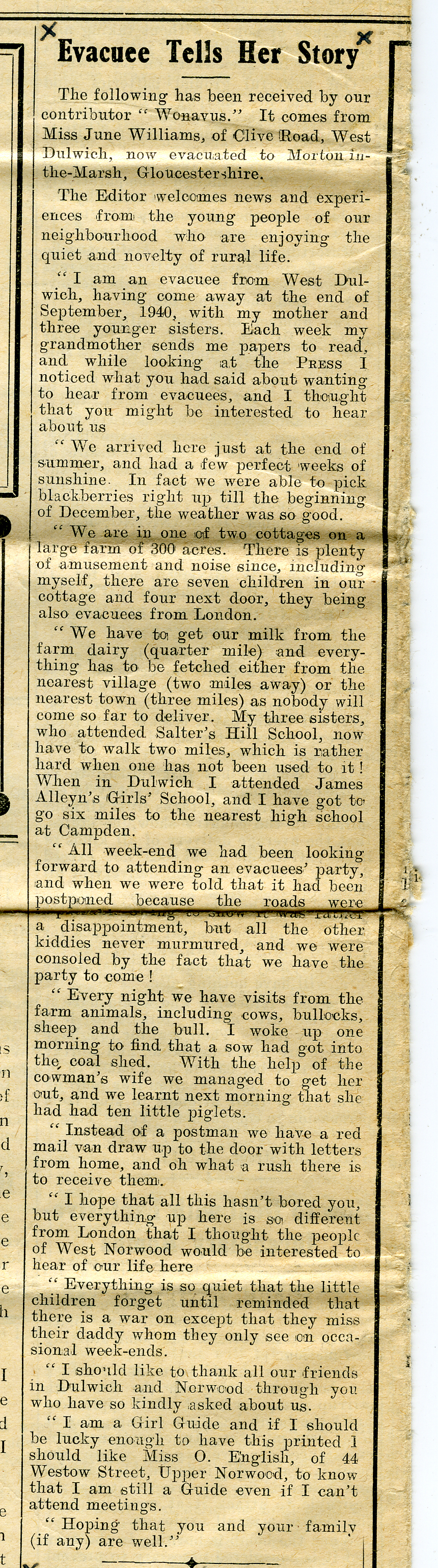

"Evacuee Tells Her StoryThe following has been received by our contributor "Wonavus". It comes from Miss June Williams of Clive Road, West Dulwich, now evacuated to Morton in the Marsh, Gloucestershire. The Editor welcomes news and experiences from the young people of our neighbourhood who are enjoying the quiet and novelty of rural life. "I am an evacuee from West Dulwich, having come away at the end of September, 1940, with my mother and three younger sisters. Each week my grandmother sends me papers to read, and while looking at the Press I notice what you had said about wanting to hear from evacuees, and I thought that you might be interested to hear about us. "We arrived here just at the end of summer, and had a few perfect weeks of sunshine. In fact we were able to pick blackberries right up till the beginning of December, the weather was so good. "We are in one of two cottages on a large farm of 300 acres. There is plenty of amusement and noise since, including myself, there are seven children in our cottage and four next door, they being also evacuees from London. "We have to get our milk from the farm dairy (quarter mile) and every thing has to be fetched either from the nearest village (two miles away) or the nearest town (three miles) as nobody will come so far to deliver. My three sisters have to walk two miles, which is rather hard when one has not been used to it! When in Dulwich I attended James Alleyn's Girls' School and I have got to go six miles to the nearest high school at Campden. "All weekend we had been looking forward to attending an evacuees party and when we were told that it had been postponed because the roads impassable owing to snow it was rather a disappointment but all the other kiddies never murmured and we were consoled by the fact that we have the party to come! "Every night we have visits from the farm animals, including cows, bullocks sheep and the bull. I woke up one morning to find that a sow had got into the coal shed. With the help of the cowman's wife we managed to get her out and we learnt next morning that she had had ten little piglets. "Instead of a postman we have a red mail van draw up to the door with letters from home, and oh what a rush there is to receive them. "I hope that all this hasn't bored you but everything up here is so different from London that I thought the people of West Norwood would be interested to hear of our life here. "Everything is so quiet that the little children forget until reminded that there is a war on except that they miss their daddy whom they only see on occasional weekends. "I should like to thank all our friends in Dulwich and Norwood through you who have so kindly asked about us. "I am a Girl Guide and if I should be lucky enough to have this printed I should like Miss O English of 44 Westow Street, Upper Norwood, to know that I am still a Guide even if I can't attend meetings. "Hoping that you and your family (if any) are well." |

|

| June also featured in the Daily Herald when she won a public speaking contest. Shirley Williams, the former Labour Minister, came second and the coverage was along the lines Williams beat Williams.

Edward Williams, my Grandfather, became a Meter repair tester. A delicate fiddly job. His health was never very good. He had a struggle keeping himself on his feet to go to work. When my parents got married Mum said: "We lived in a horrible basement room in Gipsy Road. You had to go down three steps from the front. "They had just the one room and eventually there were two children (myself and Simon) living there. In this one room the local Labour Party ward used to meet. Some of my earliest speaking lessons came from Labour members who tried to teach me to say 'Up the reds'. The house was owned by a bloke called Davy who lived upstairs. He happened to be a Conservative Councillor and used his house as the Committee Rooms during elections. One election they put up a Labour Poster and Davy tried to cover it up. One of the Labour Party members called round the police. "A lot of councillors visited," Mum said. "They said we will have you out of here. He (Dad ) said there is a ten year waiting list. They said we will condemn it." And so they did. It was condemned and became a garage and Mum and Dad got a council flat. The council flat was at Moreton House, maisonettes opposite a tower block. Dad stood as a candidate for the council in a strong Tory seat around the Wolfington Road area in May 1956 . He himself had been presented to a GMC meeting as the latest recruit when he was only a few weeks old by his father. Mum was in the hospital on polling day giving birth to Simon. At an earlier election I was in the pram whilst Mum was taking numbers outside the polling station. June was elected a councillor in May 1956. The Williams were all very active in the Labour Party. Grandfather was the secretary of his union. The Williams basically were the ward. My other grandfather was secretary agent for Norwood. |

|

Appendix 1 William Fishley Holland was born in Yelland, Fremington, North Devon, in 1889. He was the fifth of a line of peasant potters stretching back to George Fishley. His mother was Isabel Fishley, daughter of Edwin Beer Fishley. He was one of five children, three daughters, two sons. His father died when he was five years old. At the age of 12 he passed a Labour Certificate Examination and left school. A year later his grandmother became an invalid and his mother had to go to Fremington pottery to look after her. |

| From "50 years a potter" by W Fishley Holland published by Pottery Quarterly of 1958. Fremington Pottery was the last place where the true Devonshire traditions were carried on up to the time I left it, in 1912, a year after the death of my grandfather, the late Edwin Beer Fishley; and he had inherited them from his grandfather, George Fishley, who was born in 1771 and died in 1865.

The small pottery..... probably employed a dozen or more in the times when red earthenware was in great demand for all household purposes; for cooking, containing food and water; ovens for baking bread, drainpipes for farmers, a few rough bricks and the old fashioned pantile; flowerpots and in fact anything that could be made of clay. When I came to join my grandfather, in 1900, there were four men, besides he, his cousin, John Beer, and myself; each having his own particular job. Grandfather did most of the throwing and an old man of seventy turned the wheel. One made the bread ovens, pantiles, pipes, bricks, etc. Another drove the horse which pugged the clay and carted the pots to market and customers in neighbouring towns and villages. The wagoner helped with the farmwork too, for we grew our own corn, potatoes and food for the horse. How self supporting and independent we were and how full our life! When the old buildings were in existence it was a most interesting place, as one could see how it had developed, by the styles of the various chambers. The kiln was, of course, the first thing to be erected, and it was built into the slight slope of the yard. This meant that some of the rooms were on the ground level, as were the fireholes; then there was a slipway leading up to the kiln doorway and a series of chambers on the same level. These had been built at various times as they were needed and as they could be afforded, and their styles and construction always intrigued me. They took rough poles and put the ends into holes in the walls, fairly close together, then straw was spread over them, and two planks side by side made the runway. On this we walked as we carried the pots from the kiln to be stored in the bays along the chambers. During the course of time, the dust had covered the floors, until they looked solid, but it was a springy walk. The bays were made of poles of smaller sizes. The windows were just a hole framed with wood and there were a few shelves made of similar poles. I have never seen anything more primitive yet so entirely suitable for its purpose. Down in the workroooms the walls were of the same construction, but here and there hand made rough bricks formed the doorways and windows and iron rods were used instead of wooden battens to hang the pantiles to lessen fire risk. The smoke of ages had covered everything with a treacly coating which did not seem to be inflammable, and it hung like stalactites from the roof. All floors were of natural earth, worn hard with the tramping of feet. The walls surrounding the storage place, or 'clayain', were made of large pebbles from Westward Ho. These kept the clay clean and free from lime, which has a deleterious effect if present in firing. Those old potters certainly knew their job and also how to use the things they found at hand. The only thing we got from afar was small coal for firing and galena, or lead ore, and a little ground flint. Old baking ovens which had cracked in firing were upended to hold water for damping down the fires on kilning days. Some of them had been built into the immense walls which formed the base of the kiln, which seems to prove that there had been a pottery previously at Muddlebridge. Wherever you went round the place it was quaint and interesting and told its own story. My grandfather had built a wheelhouse and drying chamber adjoining the road, but all the rest was as old as the house. I should say the adjoining small cottage was there at an earlier date and that in it Robert Fishley had lived, but it was uninhabitable in my time. The bay into which the wagon was backed for loading from the ware chambers, also the stables, cart shed, pigsty and cow house, were on yard level. We kept pigs but no cow at this time. Earlier it had been the custom to keep both and the dairy was well equipped. A large vine covered the tiled roof at the back of the house, from which some splendid wine was made. We kept hens and had a fine garden, tilled by the men, with plenty of fruits, rhubarb and seakale. It was in 1902, when I was thirteen, that I came to Fremington Pottery. Since one had to be fourteen before being allowed to work in any workshop or factory, I spent my time helping on any job that I felt I could do; and if anybody turned up who looked like a Factory Inspector (through they seldom came to the pottery) I kept out of sight. My living had to be considered and I well remember the day I was called to my grandmother's bedroom and she asked me if I would like to become a potter. I had already become quite interested in all the processes, so decided in the affirmative. I did not realise then that it was a dying industry. I was told that grandfather would fit me out with clothes, boots, etc., and pay me half a crown a week together with my board. I though my fortune made... half a crown a week all my very own! For a few weeks I saved and managed to amass three half crowns, which were kept in a little wooden box given to me by a wood turner in Barnstaple. As soon as I became fourteen I visited the doctor and was passed as fit and strong enough to become a potter. First I had to learn to make flowerpots, starting with 3¼_ inch, which had to be made larger to allow for shrinkage. This was the most popular size used by the nurseries and was in greatest demand. We learnt on a kick wheel and had to watch whoever was on the 'big' wheel- turned by a man- and try to imitate what we saw. This wheel was about two feet in diameter and was driven by a belt from a large one about the size of a cartwheel situated some fifteen feet away. Old Tom turned it. The commands were, 'turn', 'steady' and he was supposed to know exactly when to slow down as the larger pieces grew, when to go fast for centring the ball and when to stop as he saw the wire cutting off the pot ready for removal. Many a time have I seen old Tom turning whilst asleep, especially when small things were being made, as the wheel would then be kept going until the board was full. The hours we worked and some of the strange customs should be recorded. We started at 6.30 a.m., stopped at eight for half an hour for breakfast, then worked till eleven, when we had the half hour lunch break. It was a tradition with the Fishleys to have a cooked meal then, and at one o'clock nothing but a cup of tea or coffee. Being a growing lad, I always wanted another good meal, much to my mother's disgust. We then worked till six in summer. As the days got shorter we stopped work when we could no longer see. There was no artificial light in the pottery, but each of us had a little oil lamp with a single wick, but no glass, and this gave just enough light for working among the pots in the drying rooms, which, being enclosed, were absolutely dark. In the dead of winter we would be finishing at 4.30. On Saturdays we had no dinner hour and worked through till four o'clock; that always seemed a long day to me. On Fridays grandfather always attended Barnstaple market. John Beer kept the stall there, selling milk pans, pitchers, etc. Grandfather kept a pig and, in season, John Beer did the killing. I helped and simply detested it. But he was very proficient, and the resulting pork was always appreciated; and as to the home cured joints and bacon- well, nothing tastes so nice now! Many men outside the butchery trade could kill and cut up a pig proficiently in those days. They took pride in anything they tackled and were versatile too. We tended the large garden and marketed the produce wholesale. The produce would be fetched by an old man from the workhouse with a donkey and cart. We grew corn and mangolds for the horse, potatoes for the family and the pigs, made and thatched ricks, tying the corn by hand. Nothing was wasted. If the clay got dirty, it was made into bricks for building fireplaces. For this we mixed ashes to open it up, Fremington clay being much too fine in texture otherwise. To get our gravel, barges went above Bideford Bridge, and worked the tides so that they got to Muddlebridge on the next high tide to unload. When Bideford pottery was working they loaded back with clay. The barge hands did not get much sleep then. All this has long ceased, as well as shipping of pots from Fremington to Cornwall, but the remains of Fishley Quay still may be seen. It is interesting to look at the reasons for changes in any craft and as I lived through those in potting, I can speak from much experience. Oven making was once a flourishing business, as the cottager had only this means of baking. There were no iron ranges or stoves- only hearth fires; and on these the women did their own baking, using barm, obtained from the local pub, for leavening. This meant keeping a barm jar, which had a bung in the top. I remember Philip Taylor's baker's cart with the words 'Best Barm Bread' on it, also the coming of the yeast stall to Barnstaple market. In towns, people sent their dinners to the local bake house to be cooked after the baker had done his batch of bread. I often saw this at Appledore. Pigs were fed from terra-cotta troughs and salted down in our salters. Cottages and villages had their wells and pumps, and so required pitchers. Milk was kept in them too after being fetched from the farms. About a hundred years ago the potter was in great demand, together with the wood turner, but the coming of cast iron, the galvanised and later, enamelware, piped water and other amenities entirely changed all that. There was little demand for what is known as slipware of the more ornate kind, as few people had any artistic taste- even if they could afford the ware. It was when many of these changes were taking place that I came to Fremington. We kept on a steady trade right up to my grandfather's death in 1912, but prices had not risen for many years, so there was little profit in potting. With all these changes, we naturally had to look for other markets so grandfather made bedroom sets, beakers, jardinieres, tankards, bowls, jugs and some loving cups and tygs in coloured pottery and slipware. He was a good draughtsman and was commissioned to make some Etruscan type vases with sgraffito decoration. Some of these were at the pottery until his death, when they were distributed among his children. Although the demand was not great, he had a few friends who appreciated the quality of his work and they held him in high esteem. His work was entirely different from the earlier Toft type of ware which his ancestors made. Red lead was used instead of galena for glazing, and it was not fired in saggars. This was the secret of the variety and beauty obtained, as the pots got alternate oxidisation and reduction and often came from the kiln with most interesting lustre and bloom. His shapes too were perfect, because, where some potters used a tool, he used his fingers to finish tops of jugs and got a much better line. In those days, there was not the variety of colours and glazes and frits available, and we relied on coarse ground copper, cobalt and iron oxides, which we ground with pestle and mortar. This gave us varied textures and, I think, more interesting. The warmth of the place on winter mornings at 6.30 was most acceptable. When there was severe frost and lots of pots about in the green state- that is, raw clay- we used what we called a devil, the sort of thing one sees being used by night watchmen. We would mix a pan of wet clay to a barrowful of small coal, tread it well and make it into balls the size and shape of a goose egg. These, placed in piles with a piece of sheet iron on top, on the draughty side, would make smoke and heat enough to keep off the frost which wet pots seem to attract. How different was the sulphurous fume of the devil from the sweet smelling wood smoke! When the chambers were filled with dried pots, John would walk round and take a mental picture of everything; and when he was satisfied that there was sufficient, we went to the kiln. Two men brought pots to the kiln door, and one handed them to John; but it took four to handle ovens. For pans of various sizes, the rings were handed in and we packed up to the doorway level. The kiln was about four feet deep. We started with tiers all round the sides to the required height. Having filled the middle, we partly bricked up the doorway. Next day, I had to stand on a plank in the middle of the kiln and hand everything to John until he got near enough to the door to reach it himself. Everything had to be carefully thought out in building this jigsaw of pots. I tended John, to learn how to finish the job. The doorway was then bricked up and plastered with a mortar of sand and clay to prevent air from entering during firing. The time came when John, getting old and rheumaticky, was often unable to work. Then grandfather asked me if I could pack the kiln. How I enjoyed that responsibility! I had been packing a day or two when John came along; and although I had planned everything, I asked him how I should proceed. He was so pleased that he recalled the incident several years after on his deathbed. He said to his daughter: 'One thing about Willie was he was never above being told.' I like to remember this. John and I were always very good friends, and I owe a lot to his excellent teaching. I still remember him as I do the jobs we so often did together. It is through him I know most about my ancestors, as he would relate stories of his boyhood as we worked. His parents had died when he was very young, and he was brought up with my grandfather, his cousin, at the pottery. He always did the fettling and finishing side, whereas grandfather was a thrower chiefly. John packed the last ships that took the pots to Cornwall. The coming of railways brought this to a close, as it did most of the North Devon shipping. I have seen seventy ships sailing over Bideford Bar when they have been held up by bad weather, or after they had been home for Christmas. The sight of those ships tied up four abreast alongside Appledore Quay is something that will never be seen again. Firing days at Fremington were busy and exciting. The kiln was 'soaked' overnight with a coal fire much slowed by a covering of cinders and a little ash. Bill Short came at six thirty in the morning to lay and light the fires which he then tended all day until 11 p.m. How's that for a day's work, ye moderns? Grandfather, even when over seventy, used to take on from then till 3 a.m. My mother suggested that I should do this turn, so I asked Bill to show me how to fire. Then I asked grandfather to go to bed; and, after watching me for some time he allowed me to continue. Afterwards I always did this turn. John Beer came at 3 a.m. and worked till we had finished- sometimes as early as 12.30, but I have known a stubborn kiln to take until 3.30. We all finished when the fireplaces had been sealed. Nobody complained about the hours being long, but I found the time dragged and the clock seemed to stand still during the nights. One seems to require much more sleep at that age than I got. John's footsteps always sounded most welcome. Three days later, we knew the result, and it was a recognised day's work for three men to empty the kiln and carry everything to its place in the chamber. From my experience of kilns, it is evident that every potter used his own judgement in the size and pattern he built, which meant that each knew the peculiarities of his firing. They built them themselves, so they were well acquainted with them by knowledge gained by trial and error and passed on from father to son- never forgetting the team spirit. At Fremington we still had the iron trough and pounders with which they pounded the lead ore a generation before. Both grandfather and John had seen this done, and they told how men got belly ache and called it colic, which was probably due to the dust from the lead. Grandfather had built a small kiln, about six feet in diameter, which was planned for a down draught and had a chimney about ten feet away. It did not answer, so they converted it to an up draught just as I joined them, and I had the experience of testing it. I can now see where they had gone wrong- by having the fireplaces too deep, their idea being to mellow the flames before they reached the ware. It was with this kiln that I had a memorable experience. One summer night I lay on a six inch plank, half open to the stars, and must have slept for about two hours. When I woke the fires were almost out and the fireplaces cold. Although I bustled round and got them going by the time John came they were very much behind and I had to explain what had happened. The kiln was late next day, but grandfather never mentioned it to me, so I think John again shielded me. When the pots came from the kiln, there were some basins for bedroom sets in biscuit at the top and they were all marked with a crocodile skin pattern. The slip had chilled and pulled back. When these came from the glaze kiln they were most unusual and beautiful and sold at a higher price because they were unique. When visiting Ray Finch's pottery at Winchcombe, which he took over from Michael Cardew, I was shown some pinch gut pitchers which he told me came from Fremington and were made by my grandfather, whose photo he had. He was greatly surprised to know that I made them and that John had bowed them. I had still to find out the way to glaze the finer pots which grandfather made. Unfortunately he died before I had accomplished all this. In his desk was a very old book in which he had written some of his early experiments. I studied this and eventually found an interesting entry showing how he had tried various ingredients in different quantities. Alongside he had commented thus: good, very dry, fair, best. I was able to gather some useful information, but I did not know what all the symbols meant. I lacked the key. However, it was not long before I discovered the secret and much else besides in connection with grandfather's glazes, although I had to go a long way round to get there. With some help from John, who knew where everything was kept, I eventually made a trial, but it was wrong. One night I had a vivid dream in which I saw the hiding place of the key, and, relating this to my daytime experience, I have always considered the key to have been itself locked up in John's mind. Grandfather used red lead, flint and stone, the most successful trial having two parts red lead to one each of flint and Cornish stone. I have since found that a little china clay improves the glaze. This makes a good transparent glaze, but if black oxide of copper is added in various proportions, some brilliant greens, running right through to a blackish lustre, are obtained. This was on a red body, fired up to 1,000°_C. We used this base for most of our glazes for many years, but we now use a Lead Bisilicate. If we wanted a matt effect, we increased the china clay and flint, as the lead is the flux and in too great quantities gives crazing. The great thing in pottery is to observe the peculiarities of any particular glaze and to make use of them. Grandfather's yellows made with red oxide of iron, sometimes nearly an ounce to the pound, were beautifully full and varied. This glaze needed to be put on thicker; otherwise, due to the iron, it had a starved appearance. Violets from manganese were less popular, though I thought them extremely pleasing. Fashions change and there is usually one colour which sells better than others for a period. I well remember when matt glazes became fashionable and one of my fellow potters simply added enough hardening ingredients to dry his glaze to a very dull and, I thought, uninteresting finish. It sold well for a time- till people found that it held the dust. It was no use offering shopkeepers anything bright, they just would not look at it. My thoughts go back to the many interesting little events that used to make up our daily life and how we enjoyed them. Each of us took a personal interest in the detail of the job in hand, so that our lives seemed full and happy. We would sing at our work whenever possible, and the songs of our day were more melodious and had a longer life than the jazzy stuff of this age. We had the hurdy-gurdy paying regular visits and knew the tunes by heart. When a new type came with what sounded like a mandolin accompaniment we thought it perfect. This music coming across the valley from Muddlebridge House will always remain in my memory. When I was a small boy, the hurdy-gurdy business was in the hands of Italians. Each week they came to our farm and always received milk and three pence. They became real old friends. They had a cage with budgerigars. For a penny, the birds would be taken out on a stick and would pick a card with your fortune from a drawer attached to the cage, much to the enjoyment of us children. Another character was a tiny man named Robins but, of course, called 'Cocky'. He was one of the early cyclists and on a Sunday would call on my mother for his 'usual'. She would cut a slice of her own baked bread and pass it under the cream standing in the pan. It made a nutritious meal for three pence. There would not be many cyclists today with roads as they were then- rough and stony and inches thick with dust, which became a slurry mud as soon as it rained. It was a problem to keep footwear clean. There were no easy shining polishes, only cakes of 'Berry's Blacking'. There were one or two motor cars in our district. One came from Westward Ho to Barnstaple frequently with ladies seated high behind a uniformed chauffeur and with their heads encased in a veil attached to a wide brimmed hat. The doctor's car was T4, one of the earliest Devonshire registrations. When one of these went along the road on a dry day it was followed by a tremendous cloud of dust and anyone passing could scarcely breathe. When the steam roller had been making up a piece of road we thought it marvellous, but the iron tyres of the horse drawn wagons soon made ruts again. Road men with shovels for loading stone, rakes for pulling them back into the ruts and a mud rake for wet days were a common sight. We have to thank Macadam for a lot. A carrier's van was our only means of transport. One came from Bideford to Barnstaple, another from Barnstaple to Bideford and either would bring our requirements from town for a copper or two. Often the carrier would be the worse for liquor by the time he reached us. He had many more miles to go and more pubs to visit. Beer was cheap (2d a pint) and strong, and he seemed to thrive on it. The horse would take him home. I was a choirboy and had to ride nearly two miles with him. Winter nights caused me some anxiety, as we could only tell where we were by the rise and fall of the road and Bill was too sleepy to keep watch. Country lads passed their time by visiting each other's stables, where they cleaned brasses, of which they were very proud, to decorate their teams of beautiful cart horses. They also busied themselves with cleaning and repairing harness, plaiting horses' manes and tails and generally caring for their well being. One of my mother's farm hands was quite good at doing quick sketches with chalk, and he would entertain us with his efforts on the wooden panels in the stable. Another could play all the song and dance tunes on the old fashioned accordion, a much smaller and simpler instrument than the organ like contraption we see today. I think that in those days many more boys played such instruments. The mouth organ was extremely popular and often played with great skill. Straw plaiting, leatherwork, shoe repairing and other crafts were considered part of one's natural education. Step dancing on a special board, to the music of one of the company, passed away many a happy hour. We would go to each other's stables and spend the evening making our own fun. For some weeks before Christmas, a few of us would get together and form a minstrel party and practice our various items in readiness. An accordion, tambourine, tin whistle, home made drum, cymbals, bones and of course the step dancer with his board. We knew which farms were holding parties, and after a tune up outside we were asked in to entertain, then given a good meal and some cider or whatever we wished to drink. All wore minstrel costumes made by our womenfolk with our help. Tin buttons were fairly easy to cut and big white collars were made from cardboard covered with linen. Faces were blackened with burnt cork. It was usually possible to find an old top hat, so we looked quite professional. The farmers thoroughly enjoyed our musical efforts, and we got great fun out of it as well as a few most useful shillings. Looking back, I should say that we were by no means lazy or devoid of imagination. By the time we had finished our rounds, all had spent a happy Christmas and New Year. It was the custom of leaders of church life to organise plays, concerts and dances, and a team could generally be found who could give a creditable performance. Only on very special occasions did we have a piano, fiddle and drum band. The old accordion player would carry on through a night's dancing for three shillings and the boys and girls (yes, and the older folk too) entered in with great zest. Election time was taken seriously. We had torch light processions for the various candidates and would sometimes take out the horses and draw their carriages by hand from village to village. Special political songs were sung to the popular tunes of the day, and we walked miles some nights. Next day we entertained each other with tales of our experiences, and the time passed merrily. My people on my father's side were yeomen farmers and Conservative in politics. I once heard my grandfather Fishley say he had voted Liberal only once and always regretted it. Socialism was unheard of but Liberalism was strong in Devon and Cornwall. As soon as I was old enough I favoured Liberalism, much to the disgust of my relatives. Most Nonconformists were Liberals and those I knew were also teetotallers. North Devon had a Liberal Member for several years, then turned Conservative. Later, in a three cornered fight, Labour polled more than the Liberals. So public opinion changes. Another popular hobby in my younger days was bell ringing. Often we visited surrounding parishes for organised competitions. In this way we made a number of friends, so that if we happened to be in their locality we were always sure of a welcome. The same applied to parties of singers. There were some comedians whose service was in great demand for village concerts, and their talent was quite up to and even better than some who perform on the BBC. Simpler things gave us pleasure and the fact that we knew all the performers added to our enjoyment. Skittles were played on a nice level piece of grass, but always with large wooden balls. Quoits was another popular game at any gathering. On such occasions as a Jubilee or Coronation, we had very special festivities. People subscribed to the prize fund and many competitions were run for folk of all ages. A favourite one was a race across the field to the tidal river, which had to be crossed at low water, through the mud, then up the road and back again. What energy this required! Yet there were plenty of competitors. The chief event was a most sumptuous tea on tables set up in the field and presided over by the farmers' wives, always with large dishes of Devonshire cream. The memory of those days has remained with us throughout our lives, but although the population has increased, villages do not seem to organise on that scale today. In the generation earlier, they had what they called club walks. The village ran a sick club to which members subscribed a few coppers each month, and when ill they drew certain benefits. On their annual club day they attended church and the wrestlers among them wore the spoons they had won in the bands of their bowler hats. Wrestling had almost vanished in my day, but old John was still drawing a little from the club, of which he was one of the few surviving members. In summer farmers organised parties to go picking mussels at Lower Yelland. At low tide you would gather basketfuls together with cockles, winkles and limpets. The first ones were brought to the womenfolk, who cooked them for the great feed when all had finished filling their baskets. Then to skittles and games, with the beer barrel close at hand. In my grandfather's time, apprentices' indentures stated that they must not have salmon more than a certain number of times per week. Salmon were caught in special weirs of which the remains were still to be seen in the river and in those days this fish was so plentiful that it was the chief food, hence the need to protect apprentices from an all fish diet. River pollution has altered all this until now it is dangerous to eat mussels and they are supposed to be gathered only for bait. A few salmon boats still fish the rivers Taw and Torridge, but catches are small, as is the rod and line catch. Our streams contained trout, which could be seen in the water under Fremington bridge. Boys tickled trout in this stream further up in the woods. One summer evening I disturbed them when they were climbing the weir of the millpond, and what a splash they made on their downward journey! We also groped for flook in the tidal steam, walking upstream at low water with hands outstretched ready to hold the fish. Besides this, in the ponds left in the sand banks in the river would be found very big flat fish, which we set about catching by treading on them. With all these sports available, country lads found plenty to amuse themselves. My grandfather, Edwin Beer Fishley, was about seventy years old when I joined him, but of course I had known him for as long as I could remember. Somehow I never looked on him as an old man, as he was vigorous and beaming and could do his day's work with the rest. He was a small man with a well trimmed white beard, a slightly hooked nose, a fine complexion and bright blue eyes which had a twinkle, especially when he was in the company of his special friends. He was not a talker generally, but was always enthusiastic on subjects which interested him. They were many and varied and somewhat above the ordinary. He loved nature, his garden, his fields, his flowers, and animals and children amused him greatly. He was generous, and although not wealthy, in fact often short of ready cash, he did his best for all his men. One thing he would not tolerate was bad language. We had an old sailor as horseman who swore habitually and I have heard grandfather threaten him with the sack. Bill would reply: 'I'm sorry, Maister, but I don't know when I'm saying it.' He really tried to avoid bad words till something excited him, then off he went into his own vocabulary quite unconsciously. All the men would do anything possible to please 'Maister'. He was happy with good books, but not novels. His office was piled with magazines and all the issues of pottery journals besides his most valued books. Grandfather's daily routine was most regular and you could be fairly sure where to find him at any time of day. He always drank coffee for breakfast (whilst we all took tea), had a cooked lunch at eleven, a nap at dinner time, ate a good tea, then in summer, after sitting down for a while he would wander off, sometimes with his gun but always with his little dog Turk. In winter, he read, or took down his fiddle and we had some of the very old tunes, which he could play by heart. To finish his day he had a tot of whisky, then off to bed to be up early in the morning and ready for work after breakfast. These were his regular habits except on Fridays, when he went to his stall in Barnstaple market. This was his recreation day, when he had a glass of beer with his friends and when he would meet visitors who were interested in pots. He could walk smartly and up rightly up to the last, although he sometimes remarked that he had 'screws'. It was said that he only attended church for weddings and funerals. Then he wore a frock coat and top hat and was really smart. He certainly was none the worse for not attending church. I am sure he had his own ideals, and those of high standard. He never grumbled without good cause; and, having stated his opinion, all was forgotten. In spring, all the men would go to the garden to do the tilling and all would have beer on those days- which they much appreciated. I suppose unions would oppose such things now, yet those fellows enjoyed every minute of it and were proud of the crops we produced. When I was able to throw any and every kind of pot, grandfather spent most of his time on his fine ware and on glazing experiments in his special cubby-hole in the old cottage. The doors and all available space were covered with records of his trials such as: 'painted plate with treacle and CuO and splashed oxide of iron', and so on. How he must have enjoyed his few years of freedom, after having to keep in harness for so long. My fiancé_e was in the Post Office at Fremington and, as we were able to share part of her parents' house, we got married when I was twenty one and she still managed the office for her father. I then had a guinea per week wages. Grandfather, considering my future, asked me if I could raise enough money to buy the pottery. My father in law was prepared to let me have some money, also an old uncle, so we talked of paying grandfather a lump sum and three pounds a week for life. Remember he was nearly eighty and wished to work as and when he felt inclined, which then seemed to be every day. Before we came to a definite agreement, he was taken ill and passed on. One cold autumn day he stood watching the thresher at the farm and caught cold. He made some Bideford jugs, then walked across the yard with a fit of coughing, went in and said to my mother: 'Very much of that and I shall soon be gone.' Inside a week he was, and without much suffering; in fact, he was cheerful to the end. I finished off those jugs and have always regretted that I did not keep one for myself. I shall never know whether or not he had discussed his intentions with his family, but his will stated that all his assets were to be divided between his four sons and daughters. It was a tremendous blow to me to lose him, possibly more so than to anyone else. The fact that I was not mentioned in the will did not seem to worry me one bit. I had faith in my ability to get on somewhere. I knew his intentions, and this set back acted as a spur. He certainly left me with the ability to earn a living, the memory of a great craftsman and a grandfather to be proud of. After my grandfather's death I carried on the pottery, doing all the correspondence and booking, in fact having absolute control. My two uncles were the executors. One lived at Torrington, the other near Exeter, and they came together only occasionally. The elder had been a potter, but he had left the trade long ago and took no part in the management. Maybe his brother had told him not to interfere with me. Unfortunately the elder uncle did not favour my being in charge and seemed jealous of the progress I had made with grandfather, which made matters a bit uncomfortable for me. It was a case of trying to please them both, yet doing as I thought best for the prosperity of the pottery. I was promised a fair deal if I carried on until the affairs were settled. After about a year, however, things got so bad through interference that I determined to bring matters to a head by giving in my notice to leave. I had no idea what was in their minds regarding the disposal of the pottery but had been given to understand that I should have every consideration. Trade had been extremely good and there was nothing to complain of financially. The handing in of my notice set things in motion. On a Sunday morning two men appeared at the pottery. They were so keen to see the place that I asked them if they were interested in buying it. One said he would not consider such an old place, but that he was from Staffordshire and was interested in our red ware glaze. He offered to give me a recipe of a matt glaze if I would give him one of ours in exchange. As three or us knew how to mix this, I saw no reason to withhold it; besides, I was not so wise then and far more trusting. Fremington estate and farms were then managed by a gentleman on behalf of his aunt and he approached me with a view to joining him in the purchase of the pottery so that we could make bricks, tiles, drainpipes and so on for the estate. We agreed that he should negotiate the purchase, and later he attended a meeting in Barnstaple which was arranged for the sale of the pottery. It then turned out that my uncle had already agreed to sell it to the man I had seen on that Sunday morning. He afterwards proudly showed me his trial of glaze made from my recipe. He had been given to understand that I would be bound to work for him. No other pottery, he seemed to think, would employ me because my association with Fremington pottery and my Fishley connections would make my intentions suspect. Just before lunch that day, the person from Staffordshire came to the Post Office to see me and told me he had purchased the pottery. After I had reminded him of the remark he made on the Sunday, he offered me a job at twenty five shillings a week. When I told him I would not consider anything less than thirty shillings he disclosed that he knew that grandfather and my uncles had paid me only a guinea a week. He evidently had been well informed about my position and had decided to adopt a firm attitude, thinking I must come to his terms. He did not know what type of fellow he was dealing with. When I set my mind on any particular course, it takes a great deal to put me out of my stride and I have always endeavoured to be a sticker. He told me he would be at the farm adjoining the pottery until the afternoon and that I must think things over and give him an answer before he returned to Staffordshire. I had absolute faith that the situation was in my control, and to his confident 'Well?' I replied: 'As I said this morning.' 'Well,' he said, 'this is where we part.' He held out his hand to say good-bye, then watched me out of sight, all the time expecting me to alter my decision. But I was adamant and would rather have taken on any job than give in. Such is the stuff of which I am made. I had not had time to consider anything very deeply, but felt an urge to go to Barnstaple, having a vague idea that something must happen. This sounds like a fairy tale, but is absolutely true in every detail. The first man I met was Mr Adam Oliver, manager of the Barnstaple Cabinet Company. He was a great friend of my family and had formerly lived at Fremington, where we had worked together on church concerts. My welfare interested him in a fatherly way. He knew that I should normally be home at work, and he asked 'What are you doing in town?' When I told him that my uncles had sold the pottery to a stranger, his reply was not very complimentary to them. He had been well acquainted with my grandfather, my uncles and everything connected with the place for many years and had seen me grow up in it. He asked what I had in mind. I told him that I had seen in our local newspaper that someone was hoping to start a pottery in Braunton, and I was seeking information in hopes that there may be a job there. Without further comment he took me a short distance to a solicitor's office and left me standing outside. When he returned he said: 'He is in and will see you. You are the very chap and I wish you good luck.' I entered the office hoping that I might be considered as a thrower, or to do some other part of the work. When I was greeted with 'Well, Mr Holland, I hear you have come to apply for the position of manager of our pottery,' I hid my surprise and replied in the affirmative. He asked all about my experience with my grandfather. Could I mix the glazes and colours that he made? What sort of trade had we been doing since his death? and many other relevant questions. I gave a truthful account of everything. My reason for leaving was satisfactory and there seemed to be no other obstacles. He then informed me that a manager had already been tentatively engaged. He was a brick maker. Could I make bricks? I said 'Yes, a potter can make bricks, but I doubt if a brick maker can make pots.' He then wanted to know what salary I required. It was all such a surprise to me that I had to proceed with great tact, but the words were given to me. I said: 'As you have engaged a manager, you have no doubt agreed on a figure; so if you would not mind telling me what that figure is, I will tell you whether or not I could consider it.' When he mentioned two pounds a week, my heart gave a jump. I replied, as calmly, as I could that I would accept that figure on condition that if and when I made the pottery pay my salary would be increased. 'Most fair, Mr Holland,' he replied. It chanced that this same gentleman had tried to negotiate with my grandfather for the purchase of his pottery some years before, with a view to turning it into a syndicate. But grandfather was a man of great independence and, although he might have made a good deal of money, he preferred to be free to do just what he wished to the end of his days. I had once tested some clay for a gentleman who had approached grandfather in the market. It was this same clay that the new pottery was to develop, but I did not know it at the time. Imagine my joy and excitement on telling my wife and my mother the good news and in thanking my great friend Adam Oliver. The appointment had come like a bolt from the blue, an event which I never cease to wonder about and which has been an inspiration to me ever since. Early next day a telegram from the Staffordshire man arrived saying: 'Your offer accepted.' My reply was very brief: 'Too late.' This must have given him a great shock, as developments proved. He knew nothing of Fremington methods, which were entirely different from those of Staffordshire. All potters have their individual ways of working to say nothing of getting to understand their particular kilns. Within a few months, when I was in the throes of getting Braunton pottery going, I was offered Fremington pottery at any figure I cared to state! It would have been much easier for me to have gone back and carried on the place I was so well acquainted with instead of struggling to get my new place in order; but I have always found honesty and playing the game is the only right and true way to live one's life. These events happened so quickly that the great uprooting gave all of us a surprise. I left the pottery on a Saturday and it was sold early the next week. I started at Braunton on the following Monday, so I have only been out of work for one week during my whole lifetime. At Braunton, I was shown an orchard. This was the site the pottery would occupy. I was to supervise the building and to state what I required. |

Strong's Industries of North Devon, 1889